The history of India in one exhibition

- Published

This hand axe is more than a million years old and one of the oldest stone tools found in Tamil Nadu state

A rare collection spanning two million years of history is on display in an exhibition in the Indian city of Mumbai.

The India and the World: A History in Nine Stories, external exhibition is chronologically divided into nine sections that together account for 228 artefacts, from sculptures and pottery to portraits and drawings.

It opened on 11 November at the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya (CSMVS), Mumbai's biggest museum. It will run until 18 February 2018, after which it is expected to travel to the capital Delhi.

Its aim, according to CSMVS director Sabyasachi Mukherjee, is "to explore connections and comparisons between India and the rest of the world".

The collection contains more than 100 artefacts from museums and private collections in India that capture key moments in the subcontinent's history.

These are displayed in connection with what was happening elsewhere in the world at the time. The exhibition also includes 124 objects on loan from The British Museum in London, many of which have never travelled beyond the museum until now.

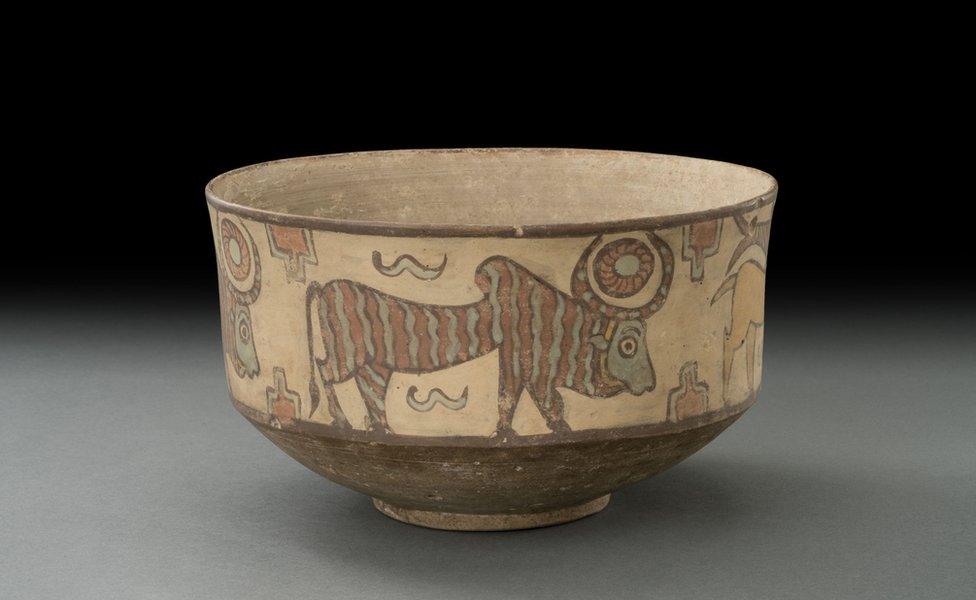

The "Balochistan Pot" (3500BC-2800BC) is made of terracotta. It was found in Mehrgarh, a Neolithic site in Balochistan province in what is now Pakistan.

Like other vessels found in the region, it is painted in multiple colours - a technique known as polychromy that was common in ancient cultures. The pottery reveals a knowledge of pigments derived from various metal oxides.

These pots were used for cooking and storage but also served a ceremonial purpose since they were found in graves as well.

The humped bull with gold horns (1800BC) is from the ancient Indus Valley Civilisation, which thrived in parts of northern India and Pakistan.

The bull was discovered in the north Indian state of Haryana. The gold horns were also common in west Asia, while the agate was quarried in western India.

This inscription on basalt rock (250BC) carries the edicts of Emperor Ashoka, who ruled one of the largest empires in ancient India, including most of modern India, Pakistan and Bangladesh.

Ashoka was believed to have renounced war and violence in favour of a more peaceful path. He spread his philosophy through inscriptions, which were put up across the Mauryan empire. The above fragment is from the ancient port of Sopara near Mumbai.

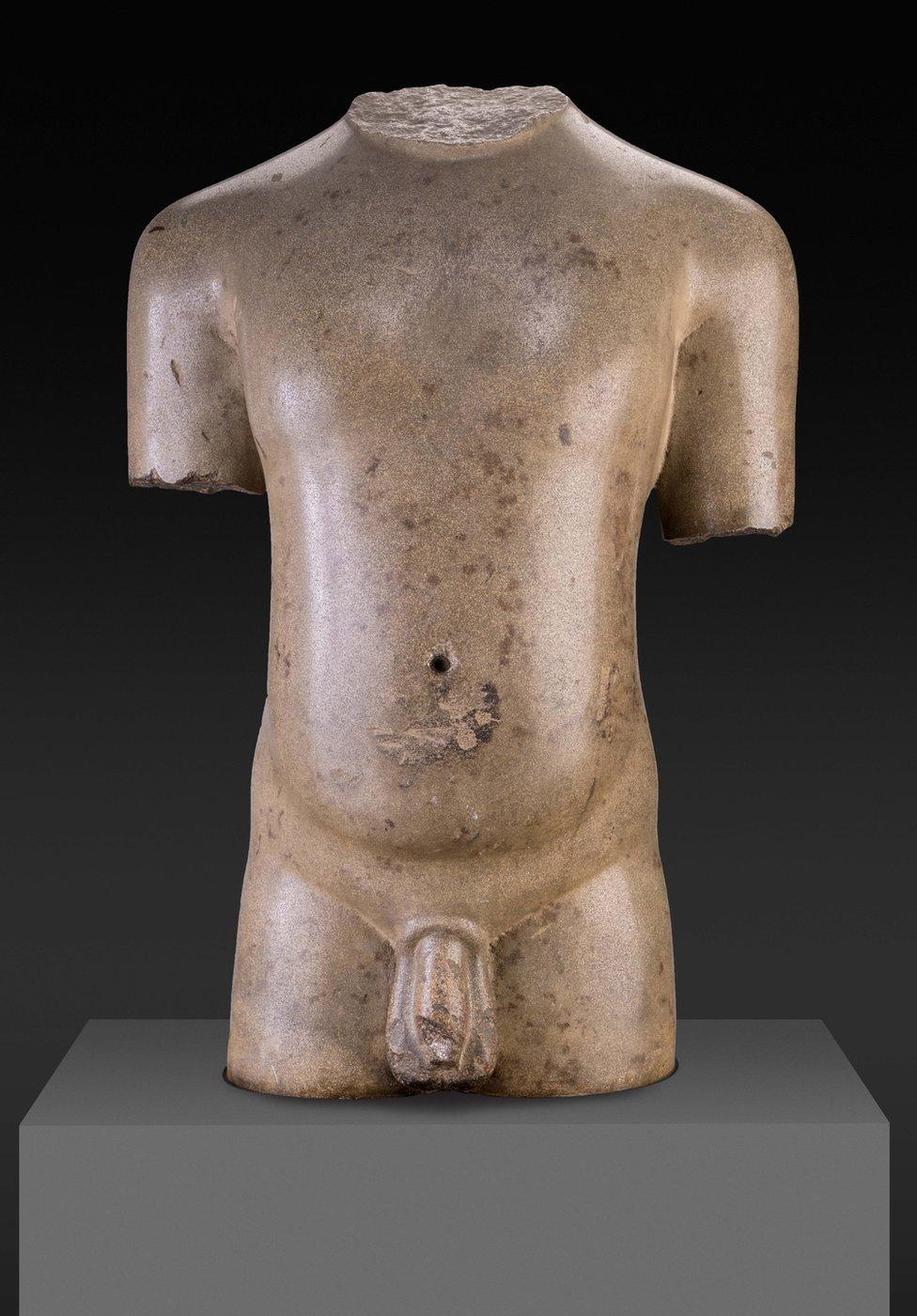

This sculpture (AD150), made of spotted red sandstone, is believed to be that of a Kushan king. The Kushans ruled most of northern India and parts of central Asia in the first century AD. It likely belonged to a large statue originally.

Many of these sculptures were found near Mathura, a town in northern India that was the capital of the Kushan empire.

This sandstone statue (200BC-AD100) is thought to be one of the earliest known images of a tirthankara (teacher) in Jainism, an ancient Indian religion.

It was found in Patna, the capital of India's Bihar state, which was the seat of many powerful Indian empires.

This statue would have served as a focus for meditation because the arms hang by the sides in a familiar Jain "posture of detachment", known as kayotsarga.

The bronze Buddha (AD900-AD1000) comes from a port town in the south Indian state of Tamil Nadu.

The town was a major centre of production for Buddhist imagery during the Chola dynasty, which ruled large parts of the country's south.

The flame on top of the Buddha's head is symbolic of his wisdom. The iconography of the flame influenced images of the Buddha in Sri Lanka and South East Asia.

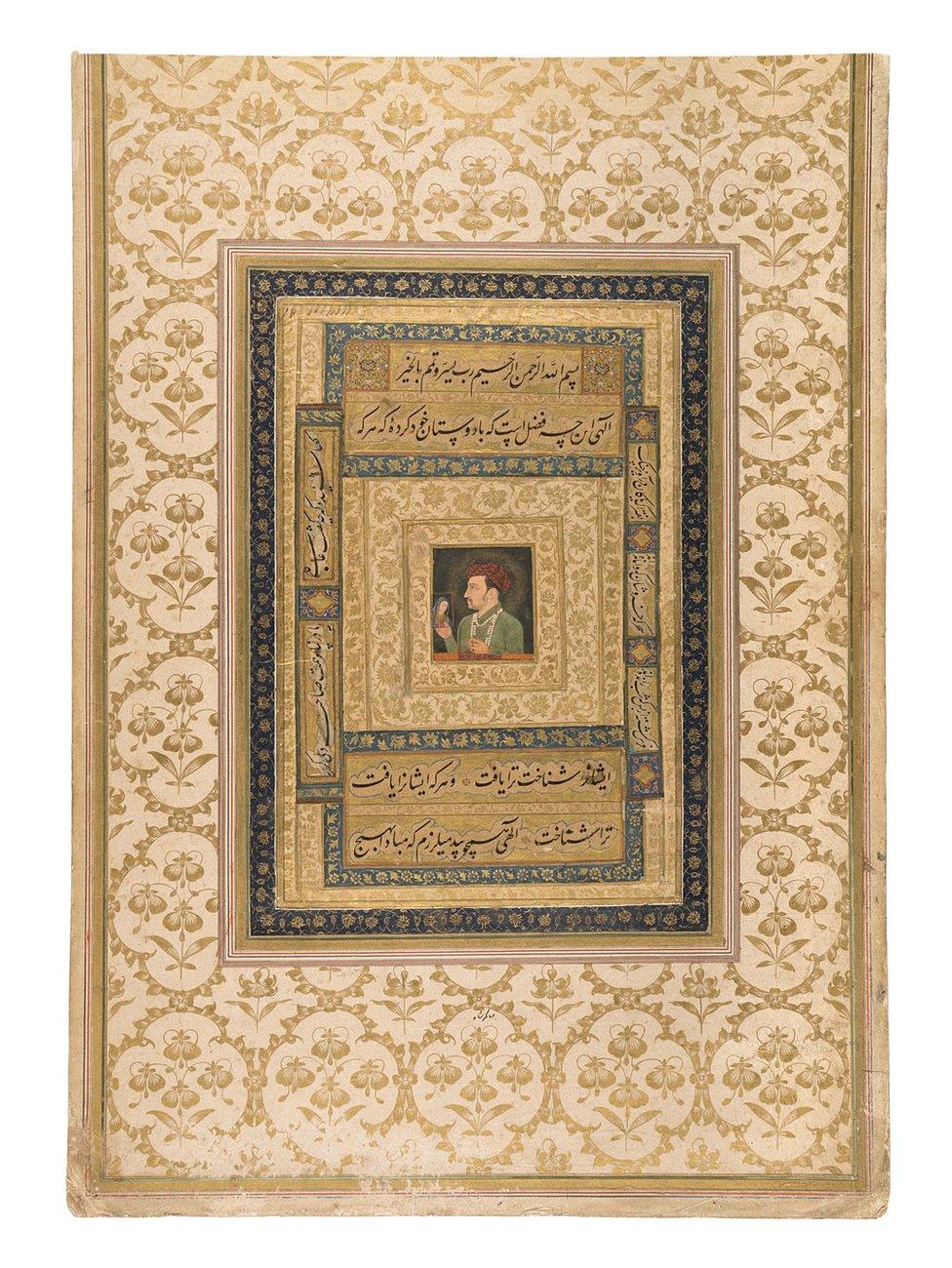

The portrait (AD1620) of Mughal emperor Jahangir holding a small image of the Virgin Mary is made from watercolours and gold on paper. It comes from the part of the northern India state of Uttar Pradesh that was the capital of the Mughal empire.

Poetic inscriptions that surround the smaller portrait ask for strength and protection for Jahangir so he can rise to the challenges of kingship.

The Virgin Mary, known as Maryam in the Quran, occupies a prominent place among women in the holy book and became an epithet for Mughal queens.

The drawing of Mughal Emperor Jahangir (AD1656-AD1661) is by Dutch artist Rembrandt. He was fascinated by the courtly life that was often the subject of Mughal miniature paintings.

Many Mughal miniatures reached Europe through Dutch trade and Rembrandt is known to have owned several of them and used them as inspiration for his own work.

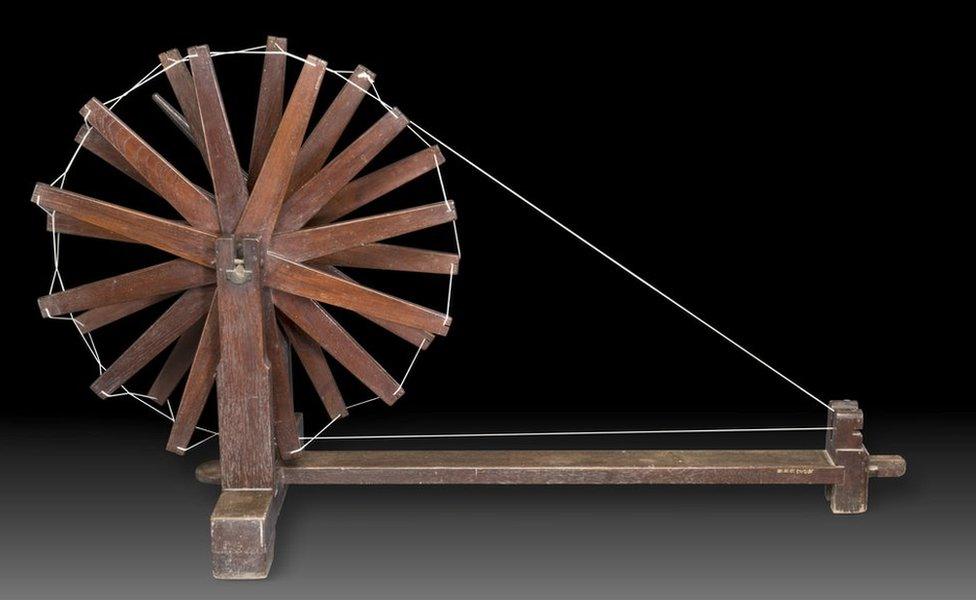

The wooden charkha, or spinning wheel, (1915-1948) became a powerful symbol of civil resistance in India's fight for independence from Britain.

It was adopted by Mahatma Gandhi to promote self-reliance among Indians. He encouraged people to spin for half an hour every day, arguing that swaraj, or self-rule, was only possible if people rejected British goods, including the cloth spun in mills overseas. Instead, he urged Indians to weave and wear only what was made in India.

This charkha comes from Mani Bhavan in Mumbai, which was the "headquarters" of Gandhi's political movement for 17 years.

The exhibition is a collaboration between CSMVS, Mumbai, The National Museum, Delhi and The British Museum, London.

- Published10 August 2017

- Published27 March 2017

- Published13 October 2017