The Indian schoolchildren who are bullied for being Muslim

- Published

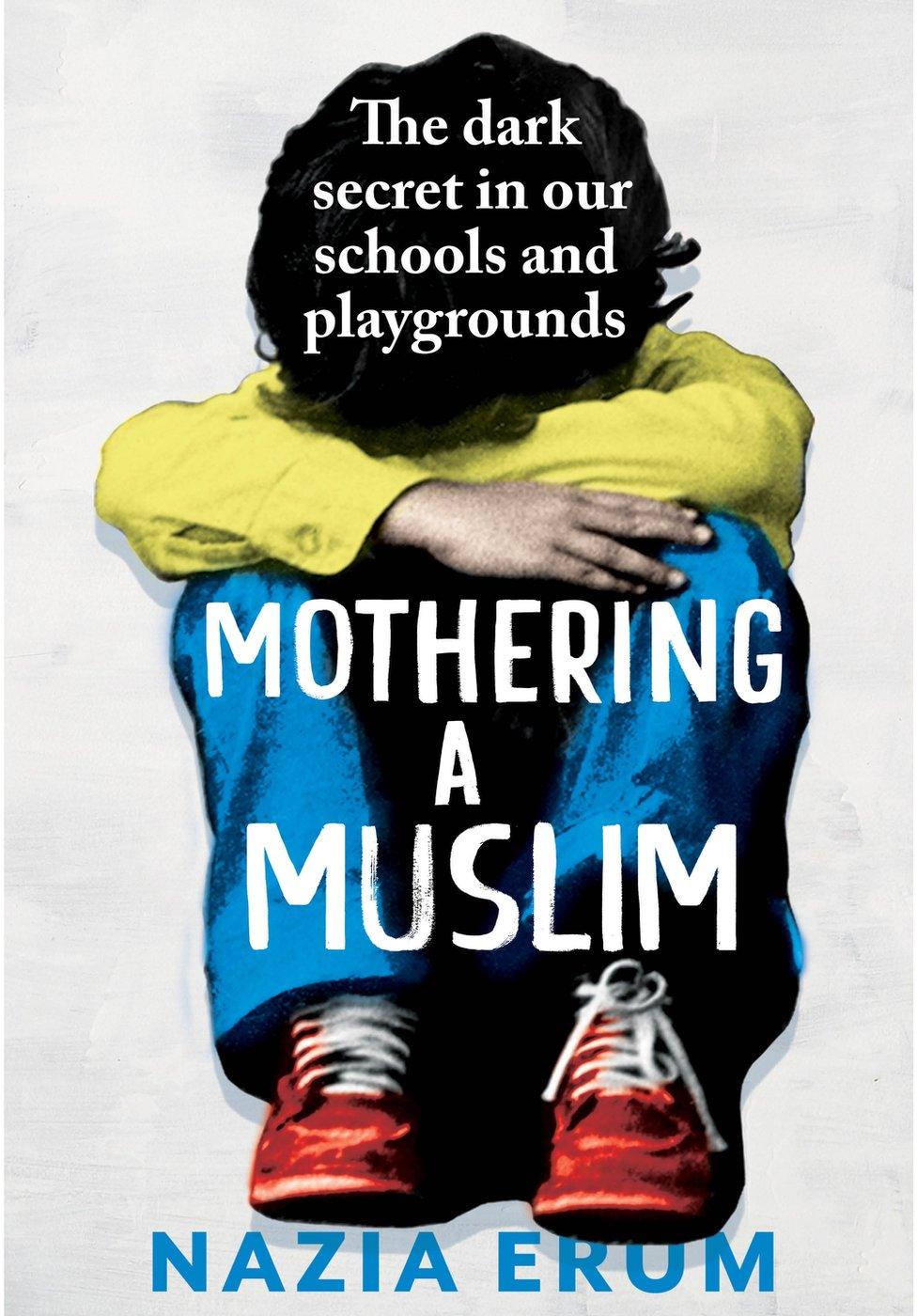

The book Mothering a Muslim says children are increasingly being targeted in posh schools for their religious identity

Schools and playgrounds can be dangerous places where children are isolated or bullied. Children often use differences in appearance, skin colour, food habits, misogyny, homophobia and casteism to inflict pain on their peers.

And now, according to a new book out in India, Muslim children are increasingly being targeted in posh schools for their religious identity because of the growing Islamophobia in India and across the world.

Writer Nazia Erum, who spoke to 145 families in 12 cities and 100 children studying in 25 elite Delhi schools while researching her book Mothering a Muslim, says that children as young as five are being targeted.

"What I found during my research was shocking, I didn't think it was happening in these elite schools," Ms Erum told the BBC. "When five and six year olds say they were called a Pakistani or a terrorist, how do you respond to that? And how do you complain to the school?" she asks.

"A lot of it is said in jest, it's meant to be funny, to evoke a laugh. It's subtle and it can seem like harmless banter, but it's not. It's actually bullying and tormenting."

The children she interviewed for her book told her about some of the questions and comments that are regularly hurled at them:

Are you a Muslim? I hate Muslims.

Do your parents make bombs at home?

Is your father part of the Taliban?

He's a Pakistani.

He's a terrorist.

Don't piss her off, she will bomb you.

Since its launch, the book has started a conversation around religious hate and prejudice in schools and last weekend, #MotheringAMuslim trended high on Twitter, with many taking to social media to share their own experiences.

Writer Nazia Erum says she was shocked to see the level of bullying of Muslim students during her research

Nearly 80% of India's population of 1.3 billion is Hindu, while Muslims make up 14.2%.

For the most part, the two communities have lived peacefully, but religious resentment has always simmered below the surface since 1947 when India and Pakistan were carved out of a single nation. The parting was bloody - between half a million and a million people were killed in religious violence.

Ms Erum says while anti-Muslim slurs have been used since the 1990s, after the demolition of the Babri mosque by Hindu hardline groups and the Hindu-Muslim riots that followed, in recent years their tone and intensity have changed.

She became acutely aware of it in 2014, after she gave birth to her first child.

"As I held my little daughter Myra in my arms, for the first time I was afraid," Ms Erum said, adding that she was worried about even giving the baby a name that could be easily identified as Muslim.

It was a time of sharp religious divisions in India. The Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party was running a hugely polarising election campaign, which helped sweep Prime Minister Narendra Modi to power.

There was a rise in Hindu nationalist sentiment and some television channels were presenting a distorted narrative that painted Muslims as "invaders, anti-national and a threat to national security".

"Since 2014, my identity as a Muslim was in my face, and all my other identities had become secondary to that. There was a sense of palpable fear among the entire community," Ms Erum says.

And since then, the fault lines have only widened. The polarising arguments and debates on television have entrenched biases, which are now being passed around from the adults to children.

"So in playgrounds, schools, classrooms and school buses, a Muslim child is singled out, pushed into a corner, called a Pakistani, IS, Bagdadi and terrorist," says Ms Erum.

The stories of children she cites in the book make for grim reading:

A five-year-old girl is terrified that "Muslims are coming and they will kill us". The irony: she doesn't know that she herself is Muslim.

A 10-year-old boy who feels shame and anger when after a terrorist attack in Europe, a classmate asks him loudly: "What have you done"?

A 17-year-old is called a terrorist and when his mother contacts the name-caller's mother, she's told: "But your son called my child fat".

Being bullied on account of one's religion in schools is not limited to India, it's happening across the world.

In the US, it's been described as the "Trump Effect", external after reports that his presidential campaign had produced an alarming level of fear and anxiety among children of colour and inflamed racial and ethnic tensions in the classroom.

So can the increased bullying of Muslim children in Indian schools be described as the "Modi Effect"?

Ms Erum says parents and schools must do everything possible to counter communal bullying

"All politicians are using a similar tone, including those from Islamic parties," Ms Erum says.

She adds that schools have refused to accept that religious bullying took place on their premises.

That, she says, could also be since most cases go unreported - children don't want to be seen as tattletales and most parents dismiss them as random incidents.

But what is worrying is that a form of self-censorship has crept into their lives and many Muslim parents have begun telling their children to be on their best behaviour at all times - don't argue, don't be good at computer games that involve bombs or guns, don't crack a joke at the airport, don't wear traditional outfits when you go out.

Ms Erum says these are warning signs and parents and schools must do everything possible to counter communal bullying.

"The first step is to accept that there's a problem, and then have a conversation about it. Whataboutery is not going to help," she says.

"If this issue is not addressed, it's not going to be restricted to 9pm debates in television studios or newspaper headlines, because hate swallows all, it impacts both the tormentor and the tormented equally."