The Kashmiri property rows that date back to British India

- Published

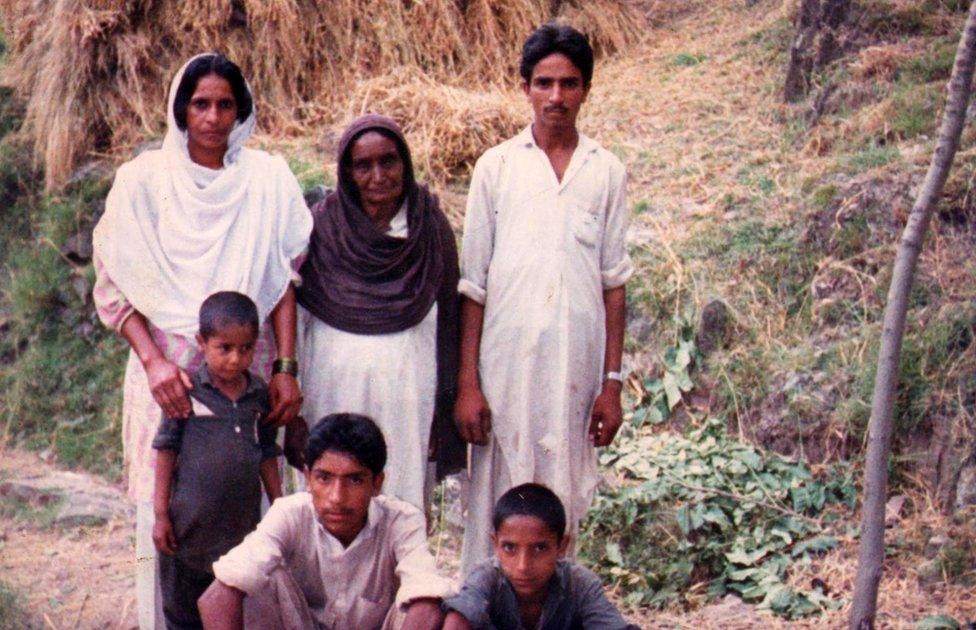

Jiwan Singh's family used to have properties, shops and acres of land - but now live here

Scores of families in Pakistan-administered Kashmir are still fighting to prove they own property lost more than 70 years ago when British India was partitioned.

Jiwan Singh's family once owned more than eight acres of land along the river in the city of Muzaffarabad, as well as more than twice that in a village to the south-east. They grew pears, apples, wheat and corn and ran several shops.

Today, Mr Singh's grandchildren are tenant farmers.

The land they claim is mired in a decades-long legal battle that goes back to the creation of India and Pakistan in 1947. Up to a million people died in the religious violence that accompanied it, and about 12 million more were displaced.

As Hindus and Sikhs living in Pakistan migrated to India, what they left behind was classified as "evacuee property". India did the same for properties vacated by Muslims fleeing to Pakistan.

But not everyone who left their homes in Kashmir - which today remains split between Indian and Pakistani controlled areas - crossed the border. Some took shelter in refugee camps. Others stayed and converted to Islam.

Seventy years on, those who stayed are still fighting for the right to their property. But all Mr Singh's family has is a court decree acknowledging their right to little more than an acre of land.

When Pashtun tribesmen from north-western Pakistan stormed Kashmir in 1947 to wrest control of it from India, their chief target was the region's non-Muslim population.

Many Hindus and Sikhs were killed or fled. Most of those who remained were later sent to India in a citizens' exchange.

Their properties - nearly 200,000 acres across what became Pakistan-administered Kashmir - were handed to a custodian of "evacuee property" with powers to allot them to "deserving" people.

On the morning of 21 October 1947 as tribal warriors invaded, Jiwan Singh had no time to take his wife and three young sons to the local gurdwara, the Sikh place of worship, where they might have been safe.

"Instead, he left them at the house of a Muslim neighbour and went out to join other members of the Sikh community who were preparing to defend their neighbourhood," says his grandson Munir Shaikh, who is now 40.

No one ever saw Jiwan Singh again, or any male members of the wider family.

Three days later, when the invaders had moved on to attack Srinagar, Mr Singh's wife Basant Kor went out to find out what had happened.

As she would later tell her family, their house had been destroyed and there were dead bodies lying around.

"She realised that she had to take her children to safety, so she decided not to go looking for her husband, assuming he was dead," Munir Shaikh says.

Basant Kor (centre) kept silent about the family property for years

Over the next few days Mrs Kor, then 27, underwent a personal transformation. She arranged to walk to the residence of a family friend, a Muslim landowner in the village of Parsaoncha, 18km (11 miles) to the north of Muzaffarabad.

There, she converted to Islam and married an ageing Muslim widower in order to secure her social position in the new world that was being born around her.

In 1954, after her second husband had died and her sons were old enough to till the land, the landowner leased them fields nearby for share-cropping and built them a home. This is where they still live.

Mrs Kor, who was renamed Maryam after she converted, never told her sons about the property the family had once owned, and never allowed them to travel to Muzaffarabad, fearing they would be arrested and exchanged for people stranded over the border.

But things changed in 1971 when her first grandson was born and she decided to speak to her eldest son.

"Dadi [grandmother] told him, 'now that you are blessed with an heir, I should tell you about your family wealth'," Munir Shaikh says.

Basant Kor died in 1997 and her eldest son Faqirullah Shaikh, who started the legal process to reclaim his family property in 1973, died in 2009. Since then Munir Shaikh has led the battle.

But their property remains elusive.

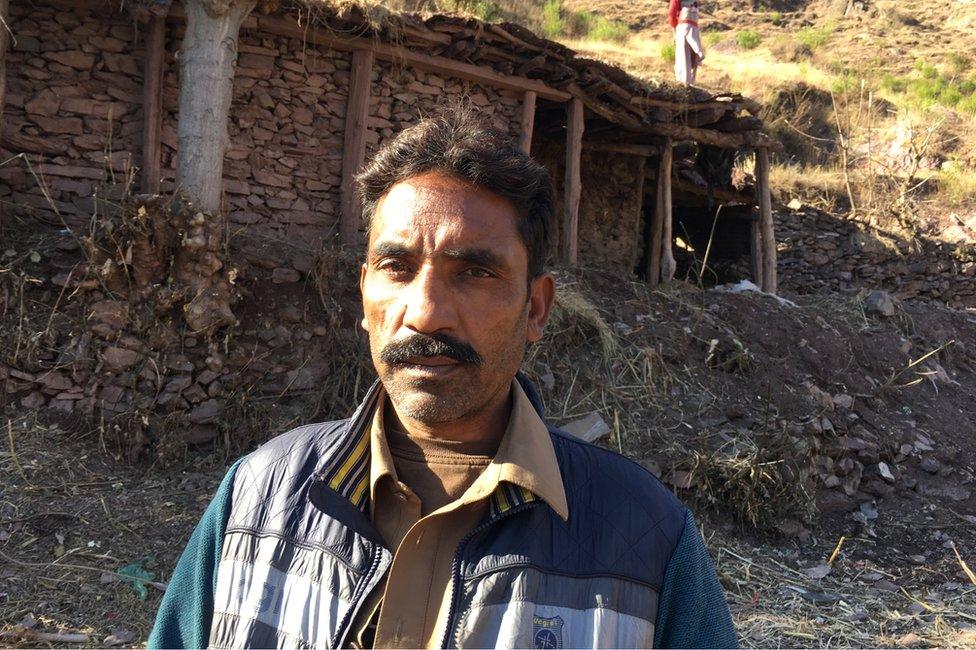

Munir Shaikh - and before him his father - have battled in the courts to no avail

"The problem lies in the legal system that the government of Pakistani Kashmir adopted after the state was split in 1947," says Manzoor Gillani, a veteran lawyer and the region's former chief justice.

Evacuee properties on both sides of Kashmir were taken over by the respective governments and kept as a trust of their real owners, pending a United Nations-sponsored plebiscite that was to decide whether Kashmiris wanted to join India or Pakistan.

"But while a Custodian Department in Indian Kashmir remains the sole caretaker of such properties, its Pakistani counterpart was given the legal powers to 'temporarily' transfer its ownership rights to a Kashmiri refugee family or a 'local destitute' - someone who owns less than two acres of land," he says.

This meant the families that were allotted such land became virtual owners of it, with the right to sell or rent it out, or use it in any way they deemed fit.

The court of the custodian of evacuee property in Muzaffarabad

This opened the floodgates for other claims - many of them, it appears, based on documents forged by corrupt officials.

"Theoretically, the law still requires the property to be reverted to the real owner if and when he or she returns to claim it," says Mr Gillani. "But there are complications; the property may have changed many hands, or its nature may have changed, entailing prohibitive fees."

Those who converted to Islam are at a particular disadvantage when wading through this legal maze - they tend to have little money and low social standing.

It's perhaps not surprising, then, that Munir Shaikh and his family have little to show for 45 years of legal battles.

Even the acre the court decree entitles them to is beyond their reach because part of it is held by the Forest Department and the rest was allotted to "refugee" or "local destitute" families, many of them influential locals with land of their own.

As Mr Gillani puts it, "a court decree is a powerful tool, provided you also have influence. Without it, a decree is just as good as the paper it's printed on".

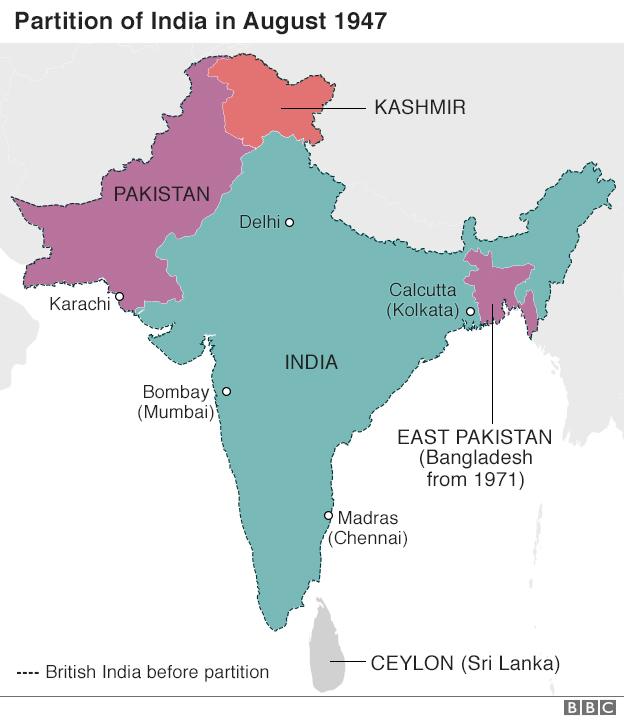

Perhaps the biggest movement of people in history, outside war and famine

Two newly independent states were created - India and Pakistan

About 12 million people became refugees. Between half a million and a million people were killed in religious violence

Tens of thousands of women were abducted

Read more:

Munir Shaikh's predicament is similar to that of Zahid Shaikh and his family.

In a quiet corner of Muzaffarabad's Naluchi neighbourhood, Zahid Shaikh, 50, shows me around his family property. It contains two houses with a family graveyard in between.

"This property has been allotted to the wife of an influential lawyer, posing as a refugee, and a court has already issued our eviction orders," he says.

When the tribal warriors invaded, his grandmother Thakuri, then a young widow (her husband died before violence erupted), took her two young sons and daughter and hid under a bridge on the Neelum river.

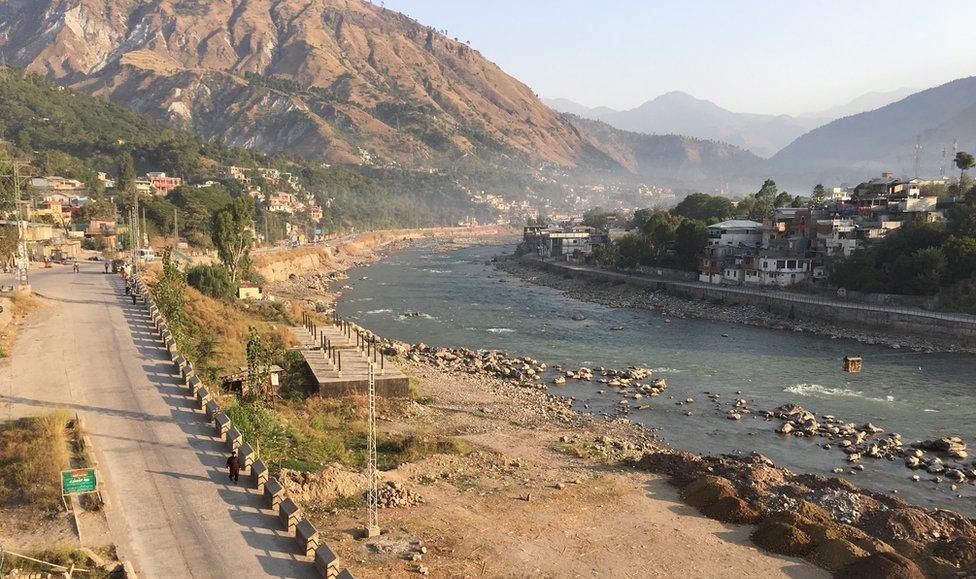

A view of Muzaffarabad, where the Neelum River divides the main city from hillside settlements

They were there for several days and at some point, her daughter was spotted by the invaders and jumped in the river to avoid capture. She was swept away to her death.

Thakuri and her sons were rescued by one of the family's former employees, a Muslim, and taken to the safety of a stranded citizens' camp at Garhi Habibullah, just across the border from Muzaffarabad, by local Muslim landowner Aslam Khan. There she was reunited with other relatives.

Her social position was secured when the landowner married one of her nieces. Thakuri then converted to Islam rather than going to India and three years later used Aslam Khan's connections to secure the property at Naluchi.

Zahid Shaikh (right) and his family face eviction and have nowhere to go

"Our house had been burnt down by the invaders, but a stone wall built along a ridge to reinforce our courtyard was still there, so Aslam Khan sent labour and material to rebuild that house," says Zahid Shaikh.

The family moved into the house permanently in 1959. Zahid's father died in 1973 and Thakuri lived until 2000.

It's not clear how but in 1990 the house was classified as "evacuee property" and allotted to others. All the family's appeals have been rejected and a court has ordered the demolition of their two houses.

The family's hopes now rest on a final appeal.

In a mercy petition sent to the prime minister of Pakistani-administered Kashmir last month, the family pleaded that if they are to be evicted from their homes, "then we have nowhere else to go, and it would be better that we are sent over to India, because we converted to Islam and are being punished for it".

- Published22 October 2017

- Published5 August 2019

- Published26 April 2017