Why the Jaws shark is not a 'man-eating monster'

- Published

The great white shark is the most misunderstood fish in the world

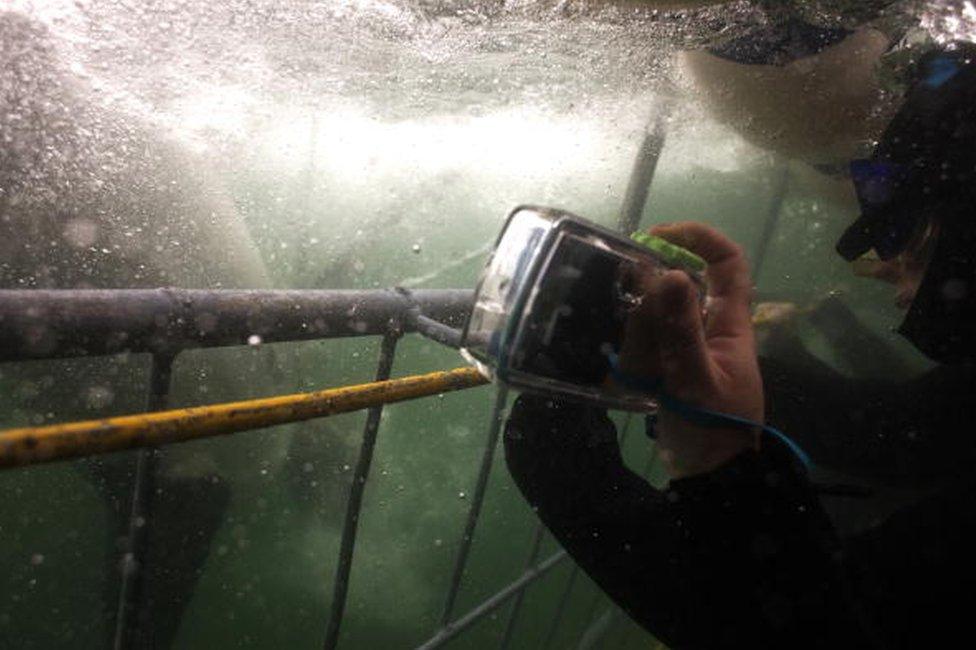

"When you're on top of the water, and you just see the fin, I think it's more scary because it's the unknown. But when you are underwater and you see the shark it is much less scary. When I saw him for the first time, he was bigger than expected and so much more colourful."

This is what a 26-year-old woman, a tourist from England, told researchers after going down in an aluminium cage into the choppy waters off the coast of Bluff, a southern seaport town in New Zealand, to watch the great white shark, the largest predatory fish in the world.

Working in what they call one of the five great white shark "hotspots" in the world, two researchers, India-based Raj Aich and his British associate, Soosie Lucas, are studying how cage diving impacts human interaction with the great white shark.

Over the past year, the two have interviewed 150 cage divers - the youngest was 12 years old, and the oldest was 70 - from some 20 countries. "Our research shows divers participating in the study return with a positive attitude towards the sharks after a cage dive," Dr Aich says.

"This helps them demystify the great white shark."

Cage diving has becoming a thriving industry across the world

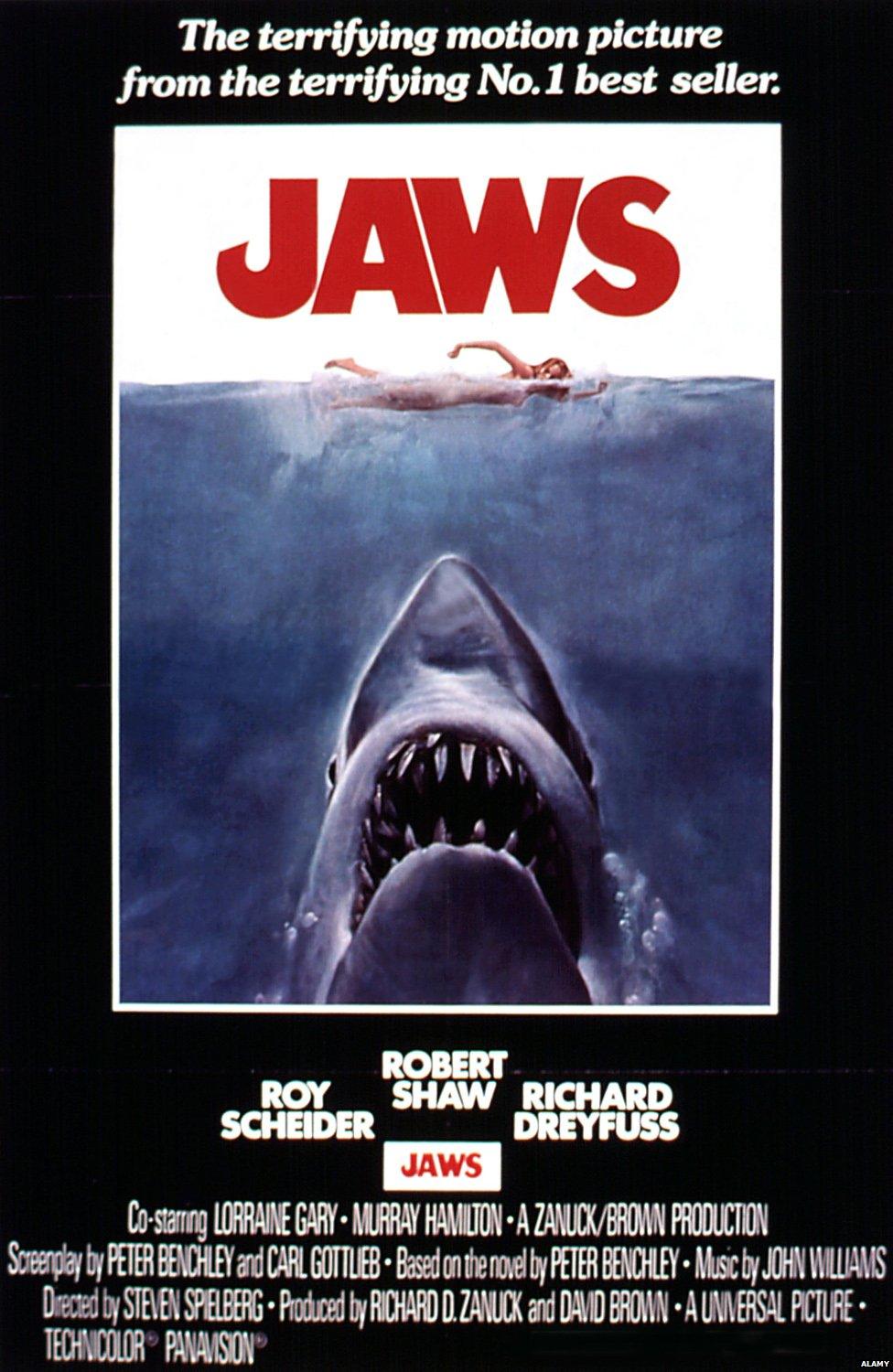

The great white shark has suffered from a crippling image problem ever since the release more than 40 years ago of Steven Spielberg's Jaws, a horror blockbuster about a shark that repeatedly attacks beachgoers in a resort town in the US.

"It is as if God created the Devil and gave him jaws," a voice drones in the trailer about the film's subject, the most maligned of the 500-odd species of sharks. It is, the narrator says coldly, a "mindless eating machine" which "lives to kill".

Since then generations have grown up with the image of a "man-eater" which glides from the sea floor to the surface, searching for human prey to catch and tear apart with its serrated teeth. Decades after Jaws, scary images and stereotypes about the shark are again being perpetuated in rating-thirsty TV shows. Two years ago, a video of a diver escaping an encounter with a great white that smashed through the bars of a diving cage off the coast of Mexico went viral and provoked scary headlines.

So much so that the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red list has put the great white on its 'vulnerable' list because of this "typically exaggerated threat to human safety and almost legendary 'Big Fish' status". The species, according to IUCN, is targeted as a source of sports-fishing, hunting (for jaws, teeth and even entire specimens preserved), sporadic human consumption or merely as the piscine whipping-boy of individuals pandering to shark attack paranoia".

In real life, the great white shark - the fish can weigh up to two tonnes, grow to lengths of 20ft (6m), reach speeds of 40mph in water and live reasonably long - prefers seals, sea lions, tuna, salmon and small toothed whales as prey. "They are inquisitive, sharp and sentient beings," Dr Aich says. "Sometimes I go down in the water after baits have been thrown, and the shark doesn't come to the boat. Or she will come for a few seconds and go away. The shark's will to encounter humans is pivotal."

The great white shark, according to shark specialist Craig Ferreira, is also "capable of explosive violence, but is absolutely not a blood thirsty and aggressive animal, and its behaviour is centred on not becoming involved in conflict and combat, with combat being the last resort."

Jaws was loosely based on a real incident in 1916 when a great white attacked swimmers along the coast of New Jersey

Shark attacks have gone down over the years: there were 84 cases of unprovoked attacks on humans in 2016, according to the International Shark Attack File. Between 2011-2016, there were 82 such attacks annually. More than half of the unprovoked attacks took place in the Continental north American waters.

Only 13 fatalities have been attributed to great white sharks in Western Australia since 1870, according to Leah Gibbs, a senior lecturer in geography at Australia's University of Wollongong.

Every day, between December and June, two boats ferry hundreds of tourists who pay NZ$500 ($363;£262) each to climb into cages yoked to boats for a view of the undisputed 'king of the ocean' in 12-degree sea water. Attracted by tuna bait, the sharks swim to the turquoise blue waters where the Tasman Sea and the Southern Ocean meet.

When the researchers spoke to cage divers near Bluff, many of them reported a "great white epiphany".

'Calm and peaceful'

They found the shark "calm, peaceful and beautiful" to look at. Others found it "inquisitive and curious". "It comes and looks at the cage just to see what is going on," said one tourist.

Watching the great white, according to a 60-year-old Canadian man, was a "moving experience, and there was no fear at all".

"People say all scary things about sharks, and as a child you are moulded into certain beliefs. But I felt totally at peace with those animals," he said. "It's a completely different experience for me than that I've seen on TV," a honeymooning American couple told the researchers, "It seems they are much more docile".

Researchers say cage diving is creating a favourable impression of the great white shark among humans

The jury is out on whether cage diving is a good way to improve interaction between humans and sharks. Ladling tuna bait in the water to attract the fish creates an "unnatural situation, leading to unnatural behaviour by the sharks,", George H Burgess, shark expert at the Florida Museum of Natural History, told me.

In New Zealand's Stewart Island, the country's third-largest island and another popular shark diving destination, local fishermen have complained about sharks following and attacking boats. , external

In Jaws, Matt Hooper, a character who plays an oceanographer and shark expert, tells the the chief of police investigating the beach deaths, "There's nothing in the sea this fish would fear. Other fish run from bigger things. That's their instinct. But this fish doesn't run from anything. He doesn't fear."

Not quite, as shark divers around the world are beginning to discover.

Pictures by Getty Images and Raj Aich

- Published2 August 2017

- Published20 July 2016