Perumal Murugan: India's 'dead' writer returns with searing novel

- Published

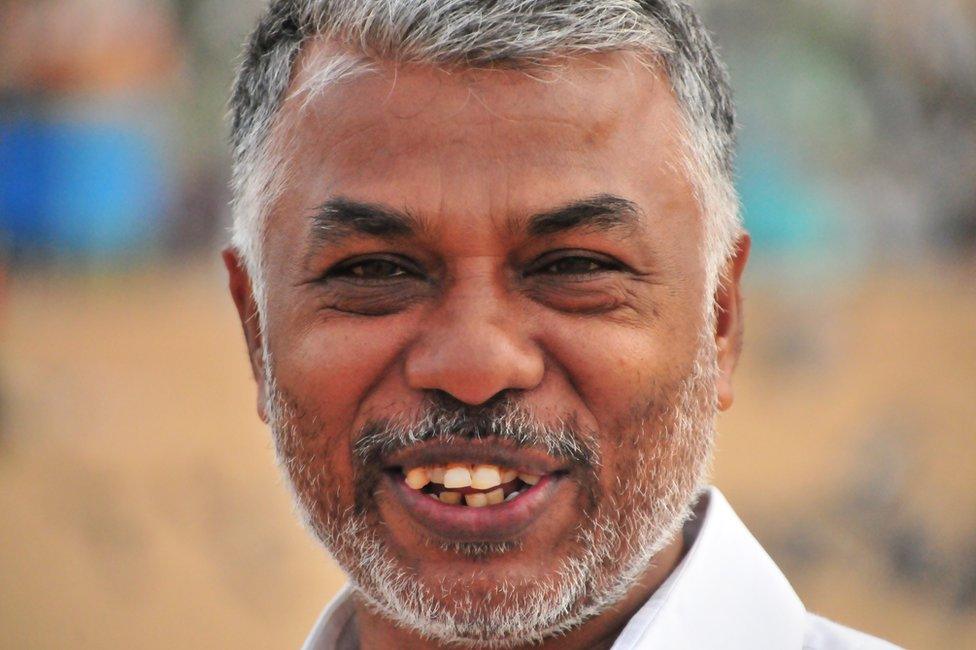

Perumal Murugan is one of the finest writers in the Tamil language

Perumal Murugan, a leading Indian author who writes in Tamil, declared his writing "dead" in 2015 after he was harassed and attacked by right-wing groups. But he has broken his self-imposed silence in a book that is an allegory on oppression and surveillance of the weak, writes Sudha G Tilak.

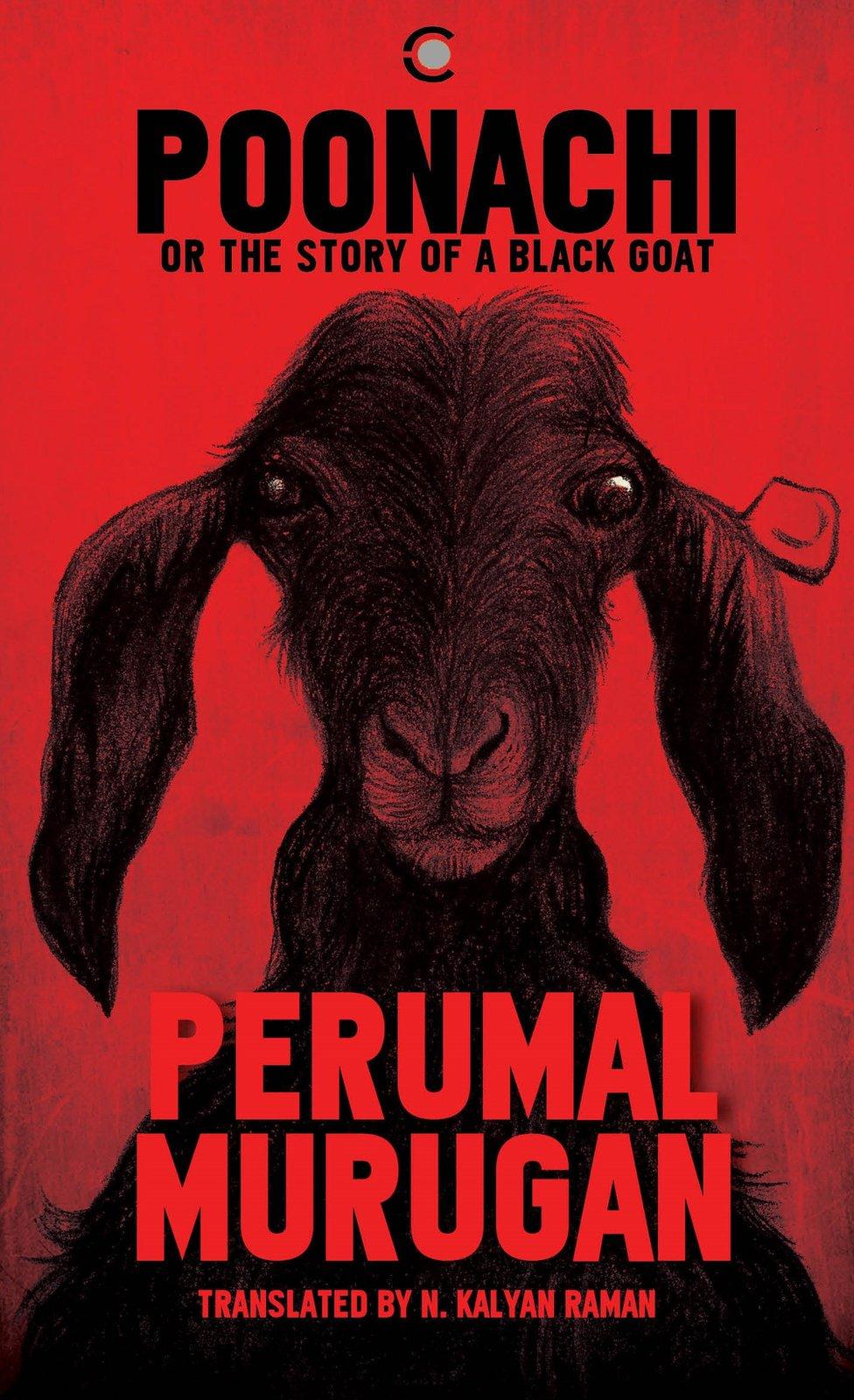

In Perumal Murugan's comeback novel, a black goat stands as silent witness to the inequities and tragic violence of the human world.

The 52-year-old Indian writer's Poonachi or The Story of a Black Goat, has been welcomed by critics as an allegory about social oppression and authoritarian surveillance of the weak and dispossessed.

Poonachi is Murugan's first novel after his self-imposed literary silence in January 2015.

He gave up writing after protests against his novel Madhorubagan (One Part Woman). The novel, set in his hometown, was about a childless woman who participated in a sex ritual during a temple festival in order to conceive - a scenario Murugan says was based on historical fact.

Local groups led protests against the book, saying the "fictitious" extramarital sex ritual at the centre of the plot insulted the town, its temple and its women.

The outcry prompted Murugan to leave his teaching job at a university, go into exile and exhort his readers to burn his books. He wrote on his Facebook page: "Perumal Murugan the writer is dead".

In July 2016, a court threw out a slew of petitions demanding that Murugan be prosecuted for his writings which had angered Hindu groups.

"The period of hiding and exile was tougher on my children and it was the sheer forbearance and protectiveness of my wife that kept me going through that bleak period," Murugan told the BBC.

Murugan's novel is the Orwellian tale of a black doe who's mysteriously gifted to an old couple

He also discovered "how deeply writing was embedded in me" during his exile.

Even with the threat of harm and violence looming, Murugan wrote over 200 poems that were released as Songs of a Coward, when the local courts dismissed the litigations against him.

Murugan says, "I realised during that traumatic period that writing is my outlet and the tool for expression at the deepest possible level".

The release of Poonachi is both sobering and reassuring.

"Murugan has redefined literary resistance with the way he fought the censorship imposed upon him," says celebrated classical musician and Ramon Magsaysay award winner TM Krishna, who has set Murugan's poems in exile to music.

Orwellian tale

Murugan's novel is the Orwellian tale of a black goat Poonachi who's mysteriously gifted to an old couple in a fictional village.

Many of his earlier novels were set in real locations and were on themes of brutal caste violence and rural unrest.

"Perumal centres most of his writing around his village experiences and this book brings out that richness beautifully. The goat being the protagonist is also symbolic of his wordless resistance against the violence that was unleashed on him by the powerful", says Krishna.

This time it's unsurprising that Murugan has peopled his novel with nameless rustic folk and asuras (mythological demons) as well as a menacing "regime" that seeks to monitor beast and man alike. The only characters with affectionate names are the goats.

Murugan gave up writing after protests over his novel Madhorubagan (One Part Woman)

"I'm fearful of writing about humans…It's forbidden to write about cows or pigs", writes Murugan in the preface of the novel.

Poonachi's tale abounds with humanism, the tragic dignity of the goats and the arduous life of the farm hands and their cattle.

He brings to bear a lyricism in the life of Poonachi's inner life. Her survival battles, the death of her lover Poovan the goat, and the loss of her children because of excruciating famine are situations that Murugan knows only too well from his experience.

Murugan writes with empathy and restraint about the hardships of the goats and it's easy to see why.

The only educated son of an illiterate farmer, Murugan grew up more in the company of women including his mother, grandmother, aunts and cousins. Heckled as a "mamma's boy" he found the company of women more conducive to his nature.

The family lived on the farm and goats were a predominant presence around the farming huts. His first pet was a female goat he named Karupayi or Blackie when he was six.

"The does were hardy and lived longer than the rams. I knew their birthing and growing rhythms as my own as they were allowed into our homes unlike the rams", recalls Murugan.

The rural world in his novels is not a pastoral romantic landscape but one of violence, greed, jealously and bloodshed that Murugan witnessed closely growing up in the hinterland.

Poonachi dies to become a deity, a figure of stone who receives mortal obeisance after the cruel treatment she received as a living creature.

In this Murugan seems to echo his personal "literary resurrection" and the attention that has come from his own near literary death.

"Writing is both my weapon and solace," he says.

Sudha G Tilak is a Delhi-based independent journalist

- Published13 October 2015

- Published15 January 2015