The ancient wisdom the Dalai Lama hopes will enrich the world

- Published

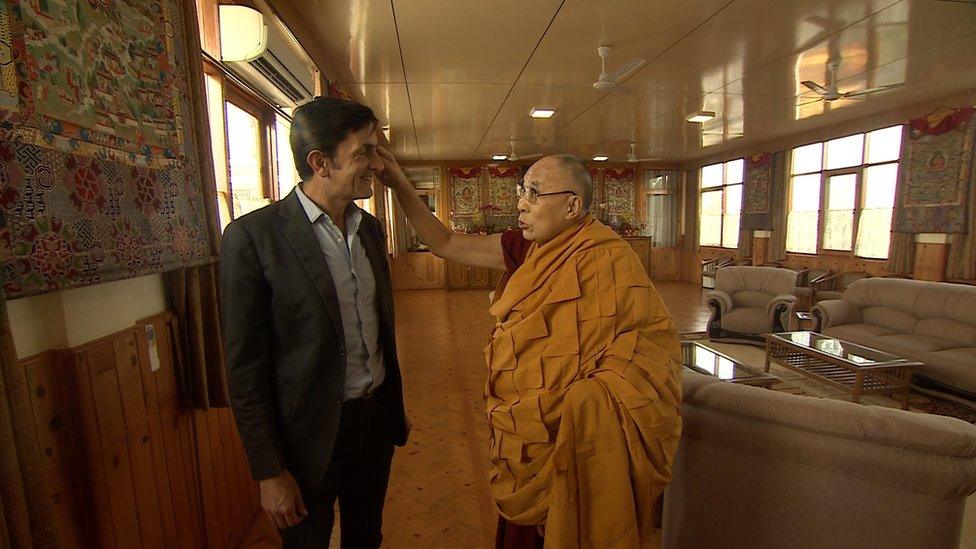

BBC correspondent Justin Rowlatt (L) meets the Dalai Lama

It isn't often you meet the leader of a world religion - rarer still that he tweaks your cheek. But that's what happened when I met the 14th Dalai Lama last month.

You know when he has entered a room. First there is a hush and, almost immediately after that, a ripple of infectious laughter. Next, there he is, his face creased into a mischievous smile, his eyes twinkling behind his tinted spectacles.

I met his holiness in Bodh Gaya, the northern Indian town where Buddha himself is said to have attained enlightenment. It is an auspicious place to meet the leader of Tibetan Buddhism, and it was also an auspicious day.

The Dalai Lama had just published the first volume, external of what he hopes will be a key pillar of his legacy- a four volume series bringing together ancient Buddhist scientific and philosophical explorations of the nature of reality.

He chuckled when I greeted him, clearly delighted to talk about the book. It draws on the wisdom of thousands of sutras and treatises written in Sanskrit by scholars in the historic university of Nalanda, he told me.

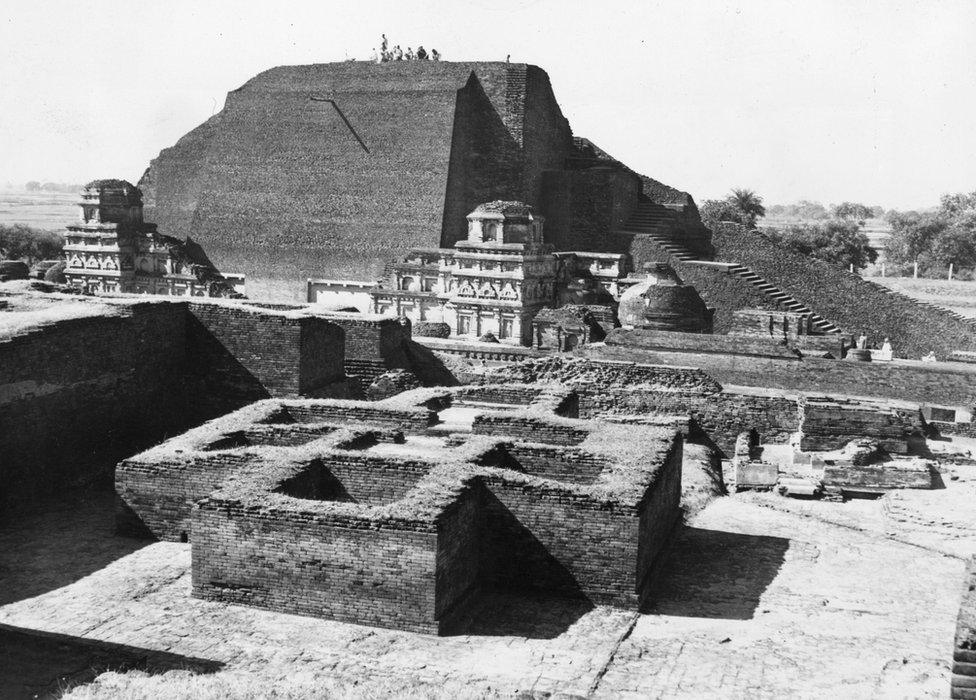

Nalanda is a legendary place, founded more than a millennium and a half ago on a site about 100km (60 miles) from Bodh Gaya in India's eastern state of Bihar.

Contemporary accounts describe an astonishing complex of temples, reading rooms, gardens and lodging houses; a veritable city with pointed turrets, sparkling roof tiles, glimmering lotus ponds and peaceful flowering groves.

It was one of the world's first universities and - at its peak - one of the greatest centres of learning on the planet, with some 10,000 students. Such was its scale that when it was razed to the ground by Muslim invaders in the 12th Century, the libraries were said to have burned for three whole months.

The only reason these ancient Buddhist texts survived the destruction, the Dalai Lama explained, is because, centuries earlier, Tibetan monks had trekked down to the hot Indian plains from their icy redoubts in the Himalayas to translate them.

They returned to their monasteries in the mountains with these Tibetan versions.

Now the Dalai Lama wants to make them available to the whole world. "The wisdom came from India", he said, giggling - everything he said seemed to be accompanied by a chuckle - "but now we know it better than the original Indian masters".

The Dalai Lama is in his early 80s now, but he's still sprightly. Apparently his doctor has told him he needs to reduce how much he travels, but looking at his schedule this only seems to mean that he now travels once a fortnight rather than every week.

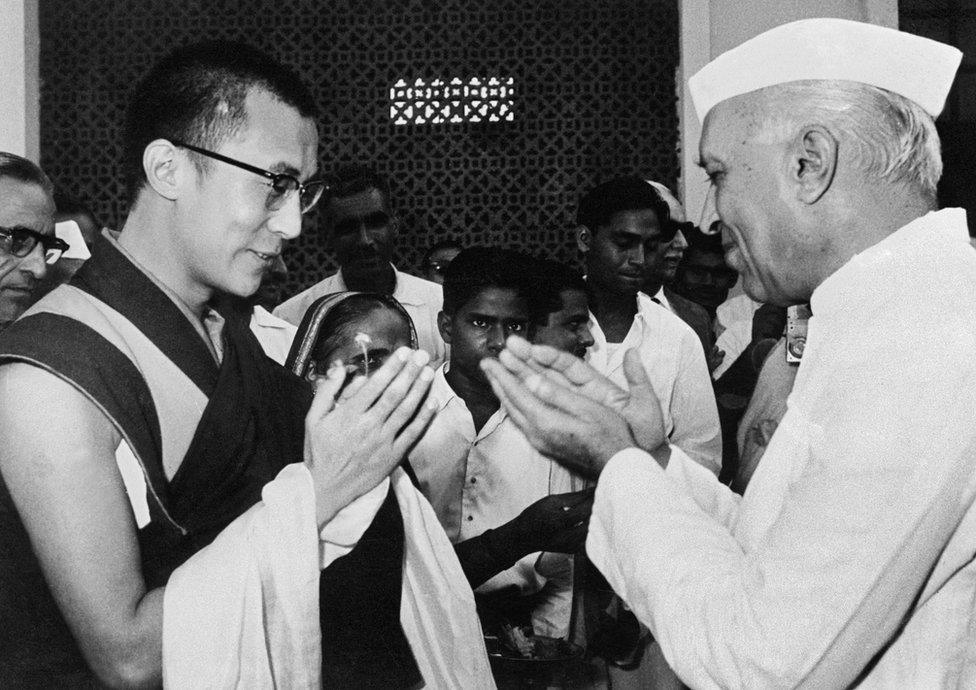

The Dalai Lama( L) and Indian's first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, in Delhi

But as he grows older, his followers have been forced to consider what will happen when he eventually passes away.

His death - and eventual rebirth - will be a major geopolitical issue. The Chinese have regarded him as an enemy - " a wolf in monk's clothes", they once called him - ever since he rejected Beijing's rule and fled Tibet in 1959 for sanctuary in India.

In exile, he's become an extraordinarily effective ambassador - not only of the Tibetan cause, but for Buddhism in general.

With his cheerful smile and burgundy robes, he has come to embody the Western ideal of Buddhism: a wise monk on a peaceful journey in search of self-enlightenment.

Buddhism needs a popular champion now more than ever.

Buddhist Myanmar's brutal attack on its Rohingya Muslim minority is just the most dramatic example of how, in South East Asia and elsewhere, the tradition has become increasingly entwined with a strain of toxic and often violent nationalism.

Ruins of the historic Nalanda University

As the leader of Tibetan Buddhism, the Dalai Lama couldn't intervene directly, but last year, as Buddhist mobs torched Rohingya villages, he urged Myanmar to "remember Buddha".

The books he is writing aim to bring the wisdom of Buddha to a wider audience. He hopes they will encourage people to study what he calls "the system of emotion" as an academic discipline. "Education everywhere is considered important," he explains.

"But if you look, the content of so-called modern education - very much orientated about material value. Not talking about inner value. So now, today, the best educated people, emotionally - lot of problem!" he says, and once again bursts into delighted laughter.

"I love to tease other people and so now I want to tease you", he tells me, rubbing my shoulder.

I brace myself.

"You see this country traditionally rich in the knowledge of emotion." He pauses, and gently tweaks my cheek with a finger: "You Britishers introduced modern education!"

There is another explosion of laughter and then his holiness moves slowly down the room, chuckling as he greets the hundreds of other people waiting to see him.

- Published21 February 2018

- Published13 February 2018