Viewpoint: The pitfalls of India's biometric ID scheme

- Published

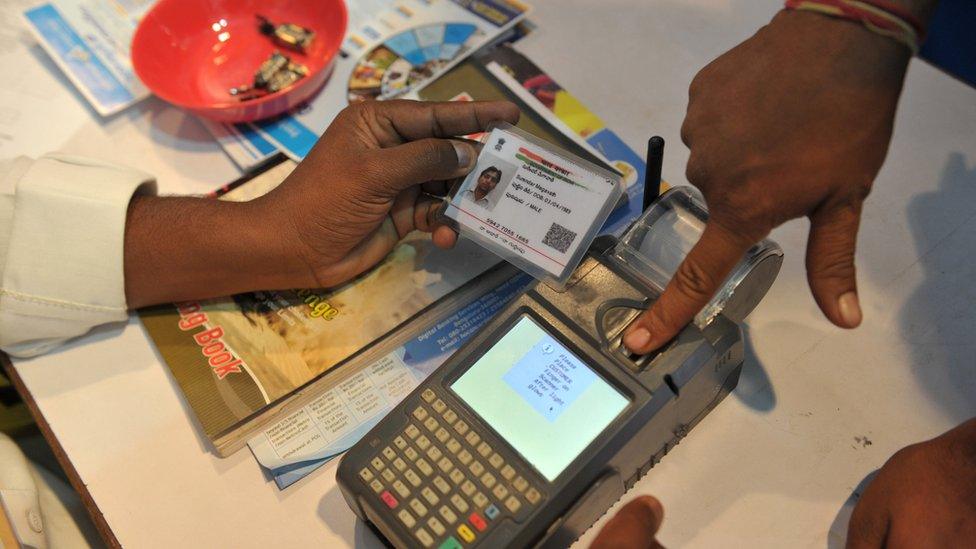

More than a billion Indians have a biometric-based identification number

More than a billion Indians now have the biometric-based 12-digit personal identification number called Aadhaar, which means foundation in Hindi. What started as a voluntary programme to tackle benefit fraud has now grown into the world's most ambitious, and controversial, digital identity programme. Mishi Choudhary writes on why most advanced countries are not adopting similar identification programmes.

If Aadhaar is such a wonderful technology platform, why are the most technologically advanced countries not scrambling to adopt it or similar structures for their people?

In many of the other highly-developed societies in Europe and North America - and in the view of many computer scientists and policy-makers who study and advocate for policy in this area - using single number identity systems for everything is simply not a good idea.

In 2010, the United Kingdom abandoned a similar scheme of a national identity card linked to biometric information.

Israel has a smart card identification system with no fingerprints where data is not stored in any centralised database but stays only on the card.

The US has no such nationwide, all-encompassing program and only two states - California and Colorado - fingerprint driving licence applications.

Biometric information is collected by most of these countries only for visitors but not for their own citizens.

Connecting bank accounts and voter registration to biometrics is a trend seen only in China, some countries in Africa, Venezuela, Iraq and the Philippines.

Biometric information is collected by most countries only for visitors but not for their own citizens

Centralised government-controlled databases of biometric and genomic data create high levels of social risk. Any compromise of such a database is essentially irreversible for a whole human lifetime: no one can change their genetic data or fingerprints in response to a leak.

Any declaration by a government that its database will never be compromised is inherently far-fetched. No government can argue that its flood prevention or public health system will never fail under the pressure of weather or disease. The goal of policy is risk management, not perfect risk-prevention.

In the case of Aadhaar, we have seen no adoption of traditional security measures well regarded in the industry to fix exploits, bugs or vulnerabilities.

What we have seen is a lot of shooting the messenger and attractive marketing to hard sell the benefits of Aadhaar while underplaying privacy and security issues.

Surveillance

Misuse of the database for state surveillance and targeted coercion is also unpreventable.

Anyone committing her data to such a system is betting for her lifetime that her government will never become totalitarian or even strongly anti-democratic, lest she be subjected to forms of oppression she cannot possibly evade.

These are not merely theoretical concerns of Luddites or anti-innovation activists but already being perfected by countries like China.

The Xinjiang region of China, which has long been subject to tight controls and surveillance has seen vast collection of DNA samples, fingerprints, iris scans and blood types of people aged 12 to 65. This information is then linked to residents' hukou, or household registration cards.

This system limits people's access to educational institutions, medical and housing benefits. Combined with facial recognition software, CCTV cameras and a biometric database, the unprecedented level of control being attained is being presented as an example of the great technological strides the country is making.

The Supreme Court is currently hearing a batch of petitions challenging the Aadhaar scheme.

The fact that Aadhaar has expanded beyond its original goals and that comprehensive surveillance profiles of citizens are already being offered by companies, confirms the fears about misuse of data for surveillance.

At the same time the risks of catastrophic failure are difficult to manage in a centralised single-number system and the problems of ordinary operation are non-trivial as well.

If an ordinary retail transaction is verified by "secure" authentication over a single-number system for instance, the seller need only surreptitiously retain both the number and the confirming biometric data in order to be able to seamlessly forge future transactions.

An inexpensive thumbprint reader meant for a market vegetable vendor, for example, can be inexpensively modified to remember all the thumbprints it scans.

Several thousands of instances where beneficiaries have been denied benefits like pension and food assistance because of failed authentication are being reported everyday from different parts of India.

To several entrepreneurs eying "data-based innovation", these are merely "teething problems" of a system that once matured will reduce all kinds of identity fraud and weed out corruption.

Multiple approaches

But to several others, it is a matter of daily survival and deprivation of subsidised food and rations that was the original intent of this scheme.

For these reasons, European and North American technologists and policy-makers prefer solutions that treat identity as a probabilistic - based on or adapted to a theory of probability - quantity.

In their decentralised approaches, multiple data sources and forms of identification are overlapped to get as high a probability of correct identification as necessary.

This means not relying on only one form to confirm a person's identity and allowing for different forms to be used to enable diversification of risk that comes from having one centralised structure.

India's Supreme Court is currently hearing a batch of petitions challenging Aadhaar.

The court had ruled through interim orders passed earlier that Aadhaar registration cannot be made generally mandatory, yet it has before it numerous petitions concerning large numbers of social services for which Aadhaar registration has been made mandatory.

We are all waiting for this powerful court speaking for the world's largest democracy on issues now coming to the fore in all societies.

Let's hope that once again the Supreme Court places India in the vanguard of the constitutional democracies and presents an example to democratic societies.

Mishi Choudhary is a technology lawyer who practices in New York and Delhi.

- Published23 June 2017

- Published27 March 2018

- Published5 January 2018