How saleswomen in India finally won the 'right to sit'

- Published

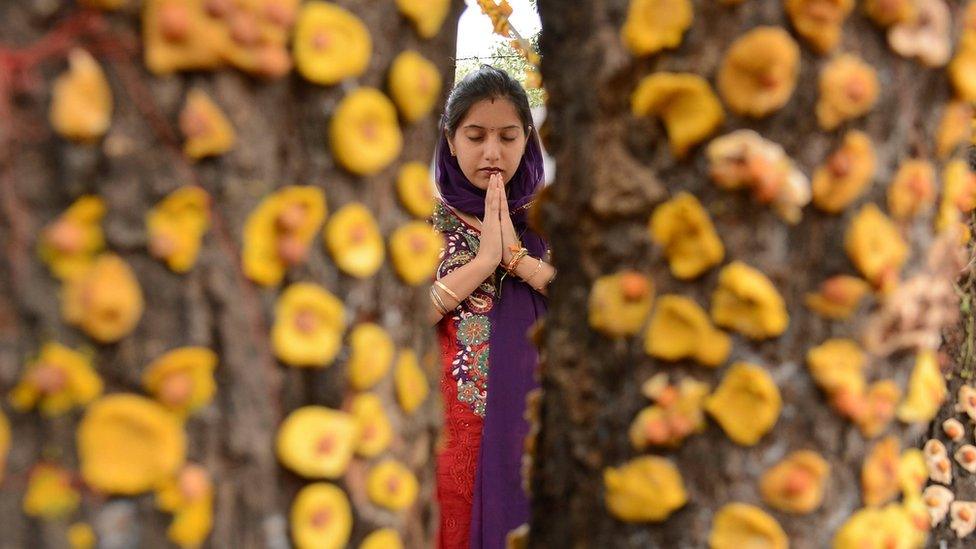

Saleswomen in jewellery and clothes stores said they were not allowed to sit through the day

A women's union in India's southern state of Kerala has won the state's workers "the right to sit".

BBC Hindi's Imran Qureshi reports on the story behind the struggle.

For years, Maya Devi worked in a shop that sold textiles - her job involved pulling out and displaying rolls of fabric, including saris, picked out by customers who wanted a closer look. But, she says, she could never sit while she was at work.

"We were not allowed to sit even when there were no customers inside the shop," she recalls. She also says she couldn't take a toilet break.

Ms Devi's experience is not unusual. Women working in textile, jewellery and other commercial retail stores in Kerala say shop owners can also prohibit them from chatting with colleagues or even leaning against the wall if they had been standing for too long.

They say their salaries were often docked if they disobeyed.

These rules were so widely prevalent that women employed by commercial retailers fought for their "right to sit" - and they won. The Kerala government said on 4 July that it would amend the relevant labour laws to grant workers the right to take a seat.

"Things which were not supposed to happen were happening," says a senior official in the labour department. "So, we have framed rules...for women to compulsorily sit and to be given adequate time to go to the toilet."

The new rules say that women must be given toilet breaks as well as access to a toilet. Shop owners can be fined if they violate the rules, according to an official.

The "right to sit" movement was led by a trade union called Penkootam

"It is so basic. One would think there is no need to write a rule that says a person needs to sit or needs a break to go to the toilet or to drink water," says Maitreyi, a trade union leader in the neighbouring state of Karnataka, who goes only by her first name.

"This is not something unique to Kerala," she adds. "It happens in other states as well."

Women make up a majority of the workforce in commercial retail shops but they are often unprotected by the law. Working conditions can be poor, wages paltry and benefits scant. Only 7% of Indians work in jobs with full benefits, according to some estimates.

Ms Devi, 43, says she never received benefits such as health insurance or a pension. She lost her job in 2014 after she tried to form a union with her colleagues so they could demand benefits and higher wages.

Viji Palithodi (standing) led the fight for the "right to sit"

She says she was inspired to fight for her rights by 48-year-old Viji Palithodi, who is the leader of the "right to sit" movement.

Ms Palithodi was 16 years old when she started her first job in a tailor's shop. During the course of her work, she says she met women such as Ms Devi who were employed by commercial retailers. When she heard their stories, she decided to do something about it. In the early 2000s, she began organising meetings where women would compare salaries and working conditions.

"Women would break down and say how they could not drink water during the summer," Ms Palithodi says, adding that they often "developed health problems because they could not go to the toilet".

She says many women complained of not being allowed to sit.

"Managers would keep track (of what they were doing) on CCTV cameras and cut the wages of those women who sat down, even when there were no customers in the shop," she recalls.

Women make up a majority of the workforce in commercial retail shops

She says some women told her that managers and shop owners had asked them to fasten a plastic bag to their underwear if they wanted to use the toilet so badly; others said male colleagues asked them if the small water bottles they carried to work were meant for urination.

"This used to hurt them,'' Ms Palithodi says. "It was this humiliation that made us think of forming a union."

So in 2009, she organised the women into a group called penkootam, which means "a crowd of women" in the local language. This eventually grew into a trade union that spread across several districts in Kerala.

Penkootam has now become synonymous with not just the "right to sit" movement but a larger fight for better pay and working conditions.

Ms Palithodi says there was a time when women would work for more than 8 to 10 hours a day at retail shops but their daily wage would be less than one dollar. Now after several years of struggles, she says, it's increased to $8 (£5.5).

This law came about, she says, because of the "arrogance of the employers and officials".

"When we complained to officials, we were told there is no rule that says you can sit."

Although such a law will soon exist, she says, the fight is far from over.

When the new rules become official, she adds, "we shall decide if justice has been done. Otherwise, we will resume our agitation."

- Published26 October 2017

- Published18 February 2016

- Published20 October 2016

- Published23 November 2015