Why young Indians are choosing streaming over TV

- Published

The recent football world cup was watched by more Indians than ever before

A record number of Indians streamed the recently concluded football World Cup on their phones, in the latest indication that many young people are deserting television for digital platforms. BBC Hindi's Zubair Ahmed finds out if these platforms pose a threat to India's numerous TV channels.

"I watched all the matches on my phone," says 22-year-old Sabir Ali, a diehard football fan, who runs a fast food outlet in the capital Delhi. "I didn't have to rush home or shut the restaurant early to watch them on TV."

Some 70 million Indians streamed the matches on SonyLiv, one of three Indian broadcasters with digital rights, and the only one to release viewership numbers so far. So, the total number is probably much higher. But that isn't surprising - in April and May, more than 200 million Indians logged on to Star India's digital arm, Hotstar, to watch the Indian Premier League (IPL) cricket tournament.

The IPL was an "inflection point" for mobile phones as a mainstream platform, says Hotsar CEO Ajit Mohan.

India is one of the world's fastest-growing internet markets, thanks to cheap data and a growing number of smartphone users. And streaming platforms, both Indian and global, have been tapping into this to target a young digital audience, which is largely ignored by cable networks.

Ajay and Vaishali Pisal, a couple who live in the western city of Mumbai for instance, do not own a TV. "When we have to watch our favourite programmes, we turn to YouTube or Voot," says Ajay.

Their five-year-old son has also never watched TV. Ajay points to his smartphone and says, "we let him watch cartoons on this."

Netflix's new Indian series stars big Bollywood actors

And the numbers for streaming platforms are impressive.

Hotstar, founded in 2015, is currently leading the pack with more than 75 million subscribers, according to an industry report at the end of 2017. A distant second with 22 million subscriptions is Voot, a free platform which is also the digital arm of an Indian media company.

Among the global players, Amazon's Prime Video has racked up more than 11 million subscriptions since its launch less than two years ago. Netflix is trailing with five million subscribers.

But JioTV, a streaming platform owned by telecom giant Reliance, could well become the country's biggest platform since it will be available to the company's 215 million internet users. But the company is yet to officially release any subscription data.

So where does this leave India's 800 TV channels? On the one hand, there are 40 streaming platforms - all of them less than five years old - that have quickly distinguished themselves.

But on the other hand, most of them are largely TV apps that allow users to stream on their phones what cable is already offering.

India is among the world's largest and cheapest internet markets

Of course, cable and satellite TV is still leading the race - some 780 million Indians watch TV, external, according to a recent estimate. Only a 100 million use streaming platforms but that number is likely to grow, especially given that 65% of India is under the age of 35.

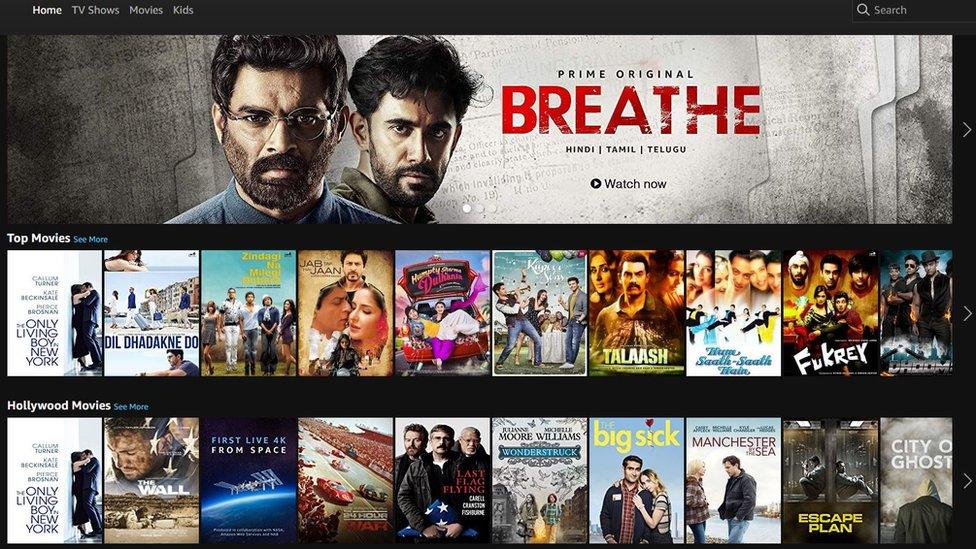

This worries senior executives at cable networks who realise that their wholesome, melodramatic soap operas, which are a favourite with many in the older generation, do not appeal to millions of young Indians. This is partly why foreign firms are investing in Indian audiences - Amazon has already made four original shows for India and seven more are reported to be in the offing.

It's also why the stories online are bolder - be it Netflix's Lust Stories, a frank, and sometimes funny, exploration of Indian attitudes towards sex; or Permanent Roommates, a popular web series on YouTube about a young couple's live-in relationship.

In 2015, Permanent Roommates became the world's second most watched web series on YouTube. It was the first series by The Viral Fever or TVF, a popular Indian YouTube channel. Their next one, TVF Pitchers, was also a huge success and brought them $10m (£7.6m) in funding.

"We, a bunch of engineers, realised young people were spending most of their time on their mobile phones," says Sameer Saxena, the chief content officer at TVF. "We thought why not give them something they would watch on their small screens."

TVF's small group of friends has now spiralled into a big company of 200, some 45 of them working on scripts and developing new formats. Its tag line - "TV is dead. Stories are not" - borders on arrogance.

But they firmly believe that there will be a remarkable shift from television towards streaming platforms. Advertisers seem to agree. In 2017, streaming platforms earned $1.66bn in advertising revenue and nearly $60m through subscriptions.

Amazon is expected to release seven more Indian shows

Streaming offers distinct advantages: you can binge-watch a whole season or watch episodes through the day, especially during long commutes.

It also offers privacy for young people living with their parents or as part of joint families. Netflix's first Indian drama series, Sacred Games, has attracted attention for its sex scenes and explicit dialogues; and while Hotstar doesn't censor Game of Thrones, Indian TV viewers are treated to a far tamer version of the series.

Many in the industry say it's an exciting time for India's video streaming market, which is growing at 30% while television stagnates at just under 10%. But some media executives say streaming platforms - and especially those making original content - have a long way to go.

"Most people are looking for excitement," says Ashok Mansukhani, a senior media executive. "We give our customers 800 channels which air a variety of programmes. TV is here to stay. Cable TV will remain a giant in the media".

Others believe streaming platforms and satellite television can help each other by creating an Indian version of the Apple TV.

"Soon you will see video streaming platforms such as Netflix and Hotstar on our platform, besides live TV," says Harit Nagpal, chief of India's premier satellite television company, Tata Sky.

- Published19 July 2018

- Published24 June 2018