Why India activist arrests have kicked up a storm

- Published

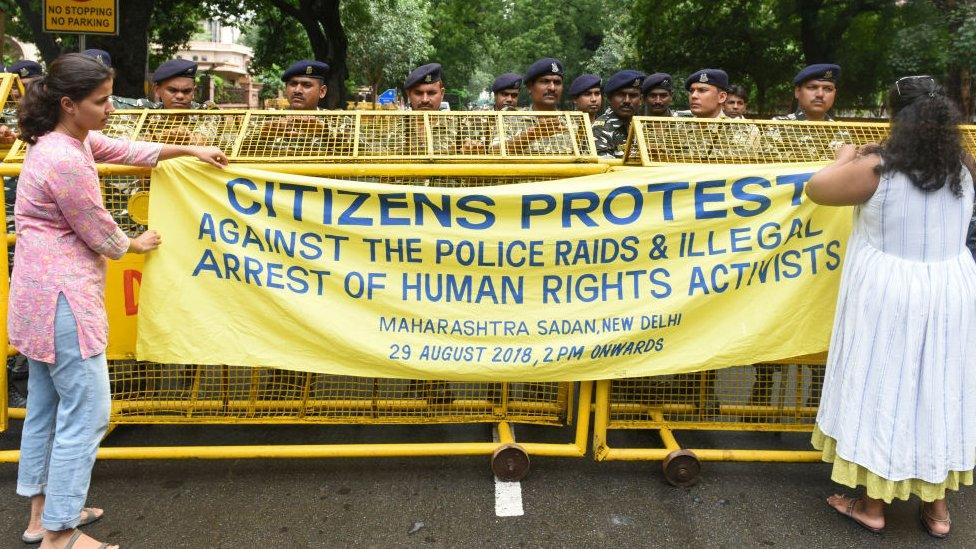

People in different cities are protesting against the arrests

The arrest of five prominent Indian political activists over their alleged Maoist links has sparked a national conversation.

Some have called it an attack on freedom of speech, while others have justified the arrests in the name of national security.

On Wednesday, a group of scholars challenged the arrests in the Supreme Court, which ordered the detainees to be kept under house arrest rather than in police custody until the next hearing on 6 September.

Who are the activists who were arrested?

On 28 August, police arrested Sudha Bharadwaj, Gautam Navlakha, Varavara Rao, Vernon Gonsalves and Arun Ferreira. They were picked up from their homes in different Indian cities. Police also searched the homes of other leftist lawyers and scholars as part of the same investigation.

Ms Bharadwaj, 56, is a law professor and a trade unionist who, for more than 30 years, has fought for the rights of tribal people. Mr Rao, 78, is a poet, a communist and a Maoist ideologue. Mr Navlakha is a civil liberties activist and member of the editorial board of an academic journal. Mr Ferreira and Mr Gonsalves are both lawyers.

All of them are leftists and are sympathisers of Maoists. They have also spoken out against successive Indian governments, including the current administration of Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

Some of them, such as Mr Ferreira and Mr Rao, have been arrested before for alleged Maoist links.

The Maoists themselves say they are fighting for communist rule and greater rights for tribal people and the rural poor.

What led to their arrest?

The reason for the arrests can be traced to a large public rally that was held in Pune city in the western state of Maharashtra on 31 December 2017.

The rally was organised by Dalits (formerly untouchables) to commemorate a historic battle against caste oppression: in 1818, Dalits fought alongside British colonial forces and defeated an upper-caste Hindu ruler.

But the day after the rally, clashes broke out between Dalits and right-wing groups, who opposed the celebrations, and one person died.

Gautam Navlakha is one of those who was arrested

Police investigated the rally's organisers, as they believed that the violence was the result of incendiary speeches at the event. And the investigation led to the arrest of five other activists - Surendra Gadling, Shoma Sen, Rona Wilson, Mahesh Raut and Sudhir Dhawale - in June 2018.

Although those arrests were reported by the media, they did not spark much outrage since the activists were not as well-known.

Police said they recovered emails, letters and other documents from them which led to the next and latest round of arrests and raids.

What are the activists being accused of?

No charges have been filed against the activists yet, but the police have said they were arrested based on "incriminating evidence" of their "elaborate communication" with members of the armed banned Communist Party of India (Maoist) or CPI(M).

They have alleged that the evidence suggests the accused provided funds to "radicalise youth and students", took part in "unlawful activities" which led to violence and have shown "intolerance to the present political system".

When Mr Rao, Mr Ferreira and Mr Gonsalves appeared in court in Pune on 28 August, the prosecutor alleged they were in the "process of setting up a front for Maoist organizations whose aim it is to overthrow the government", reports BBC Marathi's Mayuresh Konnur.

He also accused Mr Rao of buying weapons from neighbouring Nepal on behalf of extremist organisations, and Mr Ferreira and Mr Gonsalves of recruiting students for Maoist groups.

All of them have been arrested under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act or UAPA, a stringent anti-terror law under which it's much harder to get bail.

What are the defendants saying?

"The police have designed a story," Mr Gonsalves' lawyer told the court in Pune. "Finding the names of activists in some seized letters doesn't mean that they committed a crime."

Defending himself, Mr Ferreira said there was no need for them to have been arrested as he and the others had cooperated with police when their houses were raided.

Meanwhile, Mr Rao's lawyer, Rohan Nahar, argued "even the high court has clarified that merely being a member of a banned organization does not amount to an offence".

The hashtag #MeTooUrbanNaxal, is trending as people mock the term

Prominent activists, scholars and writers have also jumped to their defence.

"This is absolutely chilling," tweeted historian Ramachandra Guha. "The Supreme Court must intervene to stop this persecution and harassment of independent voices."

Why has it generated outrage on social media?

On Wednesday, filmmaker Vivek Agnihotri set off a storm on social media , externalby asking "some bright young people" to make a list of all those defending #UrbanNaxals.

There is no formal definition of the term "urban naxal". It appears to have been coined by Mr Agnihotri, who is also the author of Urban Naxals: The Making of Buddha in a Traffic Jam.

The term has since been used to describe people critical of Mr Modi or his government.

Mr Agnihotri's tweet was met with a barrage of responses - but it was not what he expected. Some 50,000 Indians replied with mocking tweets, volunteering to be on his list. And soon the hashtag - #MeTooUrbanNaxal - was trending.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

- Published29 August 2018

- Published29 August 2016