Tortured and killed: Kashmir's vulnerable policemen

- Published

Mohammad Ashraf Dar was killed in front of his one-year-old daughter

At least 31 policemen in Indian-administered Kashmir have been killed by militants this year, according to official estimates. Sameer Yasir reports on how the state's police force is bearing the brunt of the insurgency.

Mohammad Ashraf Dar was killed in his kitchen in front of his one-year-old daughter on 22 August. It was the day of Eid-ul-Adha, a holy Muslim festival.

The 45-year-old sub-inspector was posted to central Kashmir but he had come home to spend the holiday with his wife and three children.

His family lives in the tiny village of Larve, surrounded by paddy fields and apple orchards, in southern Kashmir's Pulwama district. The region has witnessed a fresh spiral of deadly violence, sparked by the killing of a popular militant leader, Burhan Wani, in July 2016 by Indian security forces.

And policemen, many of them local Muslims, have become the most vulnerable targets as violence escalates in the region.

In recent months, they have even been advised to avoid visiting their homes. If they do, they should take "extreme precautions", particularly in the southern region, said the Director General of Jammu and Kashmir Police, Shesh Paul Vaid.

'Like negotiating mines'

Dar's colleagues said he was asked by his friends and family to stay away from home but he had said he had no need to hide. "Am I a thief? I have never wronged anyone," he had said.

"The life of a local policeman fighting a homegrown insurgency is like walking on a road filled with landmines," said Ghulam Qadir, Dar's father.

Muslim separatists have waged a violent campaign against Indian rule in Muslim-majority Kashmir since 1989. The region remains a subject of bitter dispute between India and Pakistan, who have fought two out of three wars over it. India has long accused Pakistan of fuelling the unrest, a charge Islamabad denies.

The insurgency, which had begun to wane since the late 1990s, intensified in 2016 after Wani's death. When Kashmiris took to the streets to protest, security forces used "pellet guns", a kind of shotgun, against them.

Indian forces had said that the pellets, made of rubber-encased steel, were not lethal but they killed dozens of people and injured more than 1,500 others, blinding hundreds of bystanders including children who were caught in the crossfire.

Since then, the number of militants being killed has also shot up. In 2017 alone, 76 militants were killed - the highest in a decade - according to police. And this year, 66 were killed only in south Kashmir.

For decades, the Indian government did not deploy policemen in their own towns or neighbourhoods in Kashmir in order to protect their identities and their families. But in the restive south - in districts such as Pulwama - as more local youth join the insurgency, the attacks on policemen have grown.

Kashmir's local policemen are bearing the brunt of the insurgency

No militant group has recently said it killed any policeman, even in Dar's case, which was a high-profile killing.

Unofficially, police blame militant groups like Hizbul Mujahideen and Lashkar-e-taiba for such attacks.

'My daughter's innocent eyes saw it all'

The men who killed Dar knew where he lived. They crept into his house - their faces masked, carrying rucksacks and rifles slung over their shoulders - while he offered his evening prayers at the local mosque.

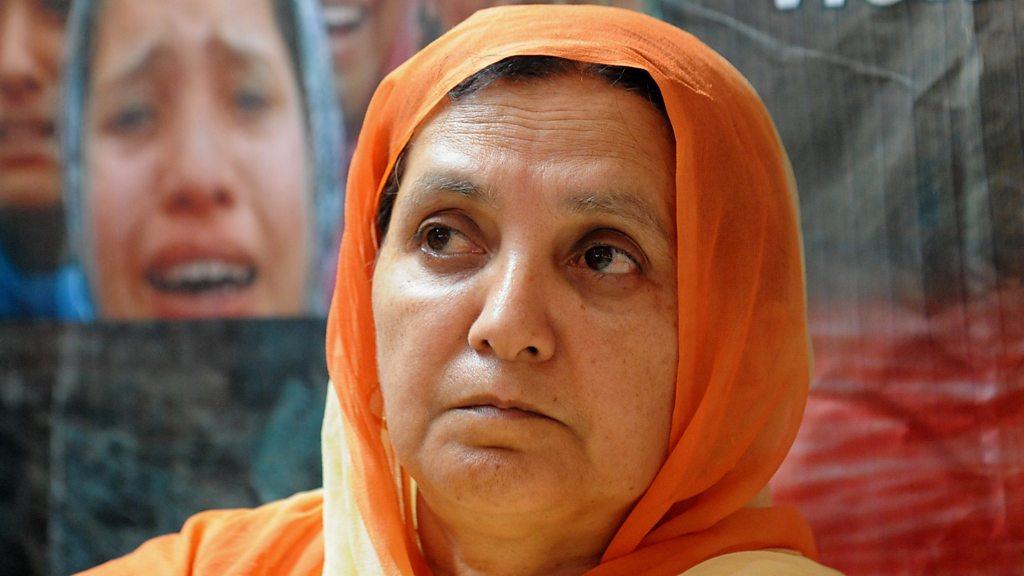

"Keep your mouth shut," they told Dar's wife, Shehla Gani, as they pointed a gun at her. They pushed her and her two sons, Jibran Ashraf, 12, and Mohammad Owaim, 7, into a corner.

"They pulled my hand and asked me where my father was," Jibran recalled.

When Dar returned home, his one-year-old daughter, Iraj, was with him. But the masked men forced him into the kitchen while he still held her in his arms. He refused to let her go but they hit him and snatched her. "You are like my brothers," Dar said to the men. "I have never harmed anyone."

Ms Gani, who could hear everything from the next room, says she then heard a volley of shots. Dar died on the spot.

"My daughter's innocent eyes saw it all," Ms Gani said.

Kashmiri Muslim women wail during the funeral of a local policeman

"Is a policeman not Kashmiri?" asked Abdul Gani Shah, 68, a resident of Mutalhama village in south Kashmir. "By targeting policemen, militants are hurting their cause."

In another incident in June 2017, Muhammad Ayub, a police officer in plainclothes, was lynched in the capital Srinagar. He had allegedly fired his gun into a crowd after getting into a brawl with some youths.

In July 2018, constable Mohammad Saleem Shah went missing while he was on a fishing expedition with friends. His bullet-riddled body was found the next day in an apple orchard.

Officials said at least 12 family members of policemen were kidnapped this year.

Despite the killings, many young Kashmiris want to join the police force

On 28 August, suspected militants abducted the son of a policeman from his home in south Kashmir. The police traced the kidnapping to Riyaz Naiko, chief of the Hizbul Mujahideen militant group. Naiko had once threatened Kashmiri policemen to "leave their jobs or face consequences".

Muhammad Aslam Chowdhary, a senior police officer, said he felt he was a target not just on the streets when he was in uniform but even inside the four walls of his home. Until recently, he was posted in Pulwama.

"Sometime you even doubt your own family members," he added.

Despite all this, many young Kashmiris want to join the police force. There aren't many jobs in the region because of sporadic violence and a weak economy.

"I would like to join the police because I have to take care of my parents," said Furkan Ahmad, who is currently training to be a police officer.

Meanwhile, the rift between Kashmiris and the police continues to widen. Protesters clashed with police in June after a demonstrator run over by a police jeep died in hospital. Police said they were defending themselves but locals alleged that they had deliberately driven into the crowd.

"Humanity is dead," said Mr Qadrim. "It's been dead in Kashmir for a long time."

Sameer Yasir is an independent journalist based in Srinagar, Kashmir.

- Published30 August 2018

- Published14 May 2018

- Published26 April 2017