The woman who fought for the right to be a prostitute

- Published

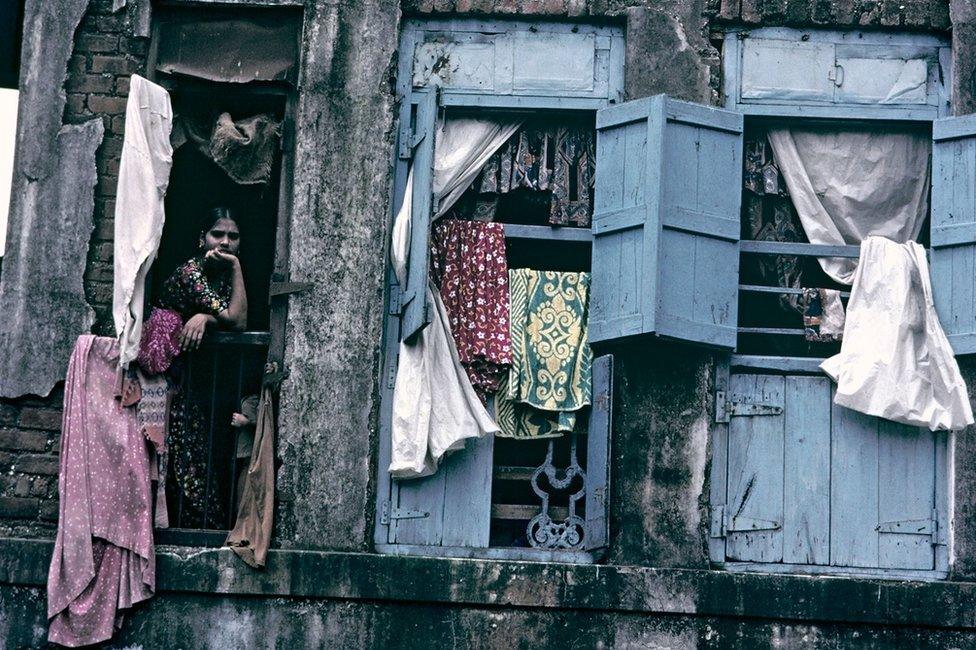

India has a thriving sex industry

On 1 May 1958, a young woman was an unusual cynosure of all eyes in a courtroom in the north Indian city of Allahabad.

Husna Bai, a 24-year-old woman, told Judge Jagdish Sahai that she was a prostitute. Invoking the constitution, she had filed a petition challenging the validity of a new law to ban trafficking in human bodies.

By striking at her means of livelihood, Bai argued, the new law had "frustrated the purpose of the welfare state established by the Constitution in the country".

It was an act of radical public defiance by a poor Muslim prostitute. She had forced the judges to look at women on the street at a time when life in India had excluded prostitutes from civil society.

Their numbers - 28,000 in 1951, down from 54,000, according to official records - had dwindled, as had public support for them. When prostitutes offered donations to the Congress party, Mahatma Gandhi refused and told them to take up spinning instead. All this despite the fact that they were among the few groups of people who were allowed to vote because they earned money, paid taxes and owned property.

Prostitutes in Bombay protested against the new law

Not much is known about Husna Bai's personal life - and a search of the archives turned up no photographs - apart from the fact that she lived with her female cousin and two younger brothers who were dependent on her earnings.

But the largely forgotten story of her struggle for the right to ply her trade is part of an engrossing new book by Yale University historian Rohit De.

A People's Constitution: Law and Everyday Life in The Indian Republic explores how the Indian constitution, despite its "elite authorship and alien antecedents, came to permeate everyday life and imagination in India during its transition from a colonial state to a democratic republic". The lack of any archival material meant that De had to depend on court records to piece together Husna Bai's story as part of a larger movement by women across the country.

Bai's petition sparked a lot of interest and anxiety.

Bureaucrats and politicians debated it and left behind "a voluminous paper trail". A group of prostitutes in Allahabad and the Dancing Girls Union came out in support of it. There was a flurry of similar petitions in courts by prostitutes in Delhi, Punjab and Bombay. Begum Kalawat, a prostitute living in Bombay state who was evicted from a town after complaints that she was plying her trade near a school, went to the high court, arguing that this violated her right to equality, and freedom of trade and movement.

The new law had made the prostitutes nervous about their future. They collected money from customers and local businessmen to fight the law in the courts. Some 75 women, claiming to be members of a professional singers and dancers association, staged a demonstration outside parliament in the capital, Delhi. They told the MPs that a crackdown on their profession would lead to its spread to respectable areas.

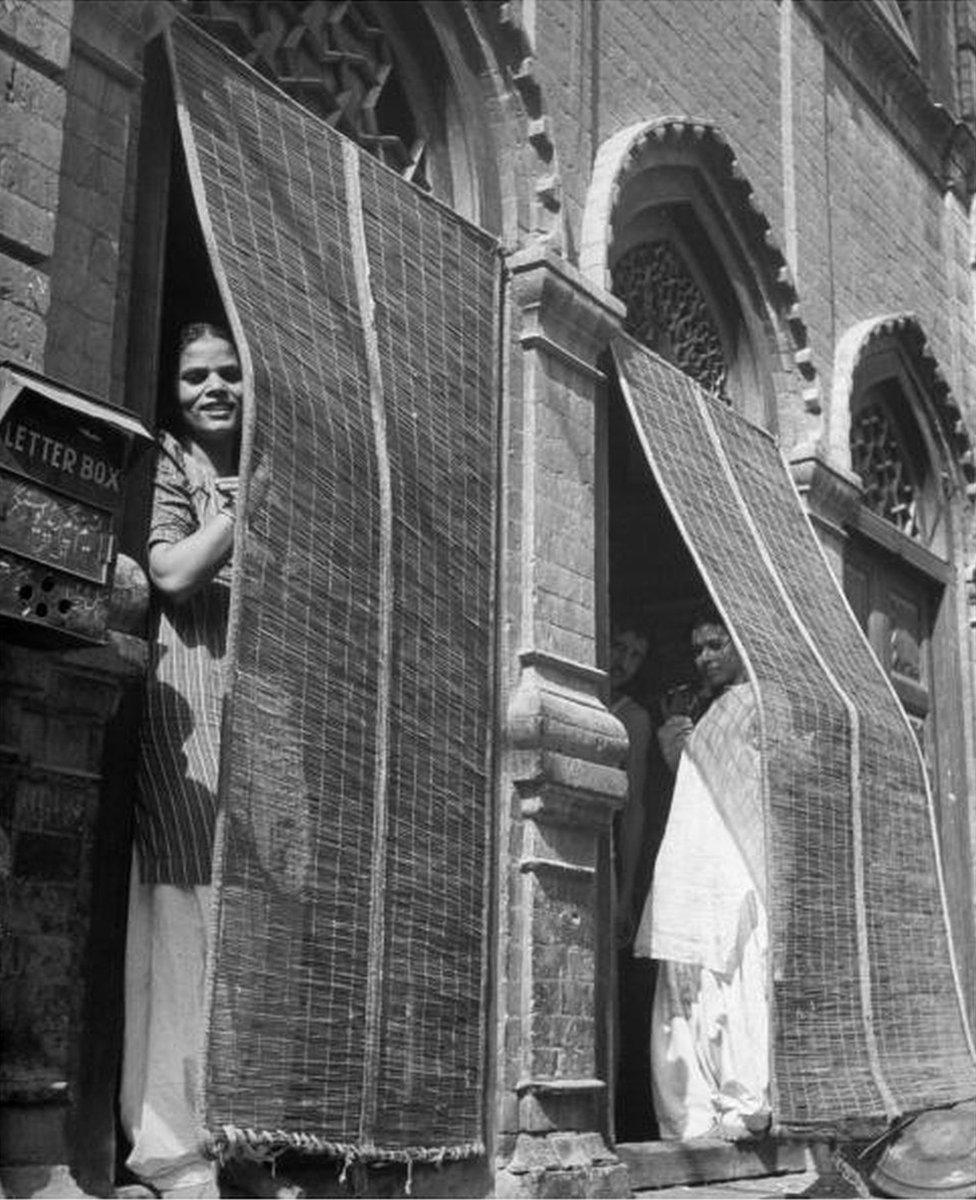

India's constituent assembly had a number of distinguished women who took a stand against prostitution

Some 450 singers, dancing girls and women of "ill fame" even formed an union to fight the new law. A group of dancing girls in Allahabad announced it would hold demonstrations in protest against the law because it was a "clear encroachment on the right to carry on any profession guaranteed by the constitution."

Prostitutes in Calcutta's bustling red-light district threatened to go on a hunger strike if the government did not provide the 13,000 sex workers in the neighbourhood with an alternative means of livelihood.

The police and the government expressed their concern over Husna Bai's petition. Not surprisingly, it met with the stiffest resistance from women MPs and social workers who had been leading the campaign for legislation against human trafficking.

The critics, says De, were "aghast at the invocation of constitutional principles by prostitutes".

"Husna Bai's petition and the similar petitions that followed it were seen as an attack on the progressive agenda of the new republic."

India's constituent assembly - which included a number of women who were experienced organisers - had argued that women did not choose to become prostitutes and they were forced into it because of circumstances. It would have possibly shocked them that prostitutes would assert a fundamental right to ply their trade and continue a "life of degradation".

"Looking closely, it becomes clear that this is not an individual heroic act of resistance but rather one part of a collective action by a loosely organised group engaged in sex trade throughout India," says De.

"It is clear that this new law added to the pressures that those engaged in the sex trade were already facing and threatened to upset long-standing practices."

Bai's petition was dismissed within two weeks on the technicality that her rights had not yet been hurt by the new law - she had not been evicted, nor was there a criminal complaint against her. Judge Sahai said her arguments on eviction were correct, but he didn't say much more.

And eventually, the Supreme Court found the law to be constitutionally sound, and said prostitutes could not enjoy unrestricted rights.

Rohit De's A People's Constitution: The Everyday Life of Law in the Indian Republic is to be published by the Princeton University Press, in US, and Penguin India