How India avoided its 'Lehman Brothers moment'

- Published

The default of IL&FS has spooked investors

India's government has taken over a major private infrastructure financing and construction group after it began to default on its $13bn (£10bn) debt repayment - and the news sparked panic in the financial market. Devina Gupta and Pooja Agarwal explain the reasons behind this crisis.

Many are calling it India's "too big to fail" moment, referring to big financial firms so large that their collapse could spark economic chaos.

On Monday, India took over the beleaguered IL&FS, an acronym for Infrastructure Leasing and Financial Services - a major non-banking financial institution, or a shadow bank. The firm's six directors have been dismissed and the new board is now led by a top banker, Uday Kotak.

The default spooked the markets and raised fears of a Lehman-like crisis, referring to the collapse of the US investment bank Lehman Brothers 10 years ago, external. The event rocked global stock markets and led to the biggest financial crash since the Great Depression.

IL&FS was set up in 1987 when a clutch of banks came together to fund the infrastructure boom which began in India in the 1990s.

The idea was to have an institution that could not only provide financial assistance but also give technical solutions for infrastructure projects.

The non-banking firm raised money through short and long-term bonds, that could be traded in financial markets. (If a government wants to borrow money, they usually do it by selling bonds to investors. The investor then gets to receive a stream of future payments.)

Infrastructure projects boomed in Indian cities focused improving transport links

Major shareholders of IL&FS include India's largest life insurance company Life Insurance Corporation, Japan's Orix Corporation and Abu Dhabi Investment Authority.

The money is invested in different infrastructure projects undertaken by private and government-run companies. Over the next three decades, the company formed 169 subsidiaries which managed a long list of investments.

However, slower-than-expected growth in the Indian economy in recent years led to stalled projects and delays in payments to the firm.

The group's venture into buying real estate in India's slowing market also backfired. As the money drained out, IL&FS defaulted on a series of its loan repayment commitments. This has shaken investor confidence in the non-banking financial institutions.

These institutions have been lending money to corporate borrowers as banks have struggled to do so due to their mounting debts. According to Reuters, there are about 11,400 shadow banking companies in India with a combined balance sheet worth $304bn and their loan portfolios have grown nearly twice the pace of banks.

But now the IL&FS default has shaken investor confidence over the stability of the non-banking financial sector.

"There are definitely some uncomfortable questions about the liquidity, assets quality and credit ratings of many non-banking finance companies. We had a lot of such firms and they have proliferated," Ananth Narayan, a former banker, said.

That makes all the more worrying the risk of a domino effect on the savings of tens of thousands of investors who have parked their money in the mutual funds which have high exposure to these institutions.

According to one study, in the last four years, fixed investment by mutual funds in non-banking finance companies has jumped by more than 2.5 times to about $33bn. Experts say the IL&FS crisis is a wake-up call.

The equity markets, too, are feeling the jitters - last week share prices of listed non-banking financial companies like Dewan Housing Finance Corporation and Indiabulls Housing Finance were under tremendous pressure.

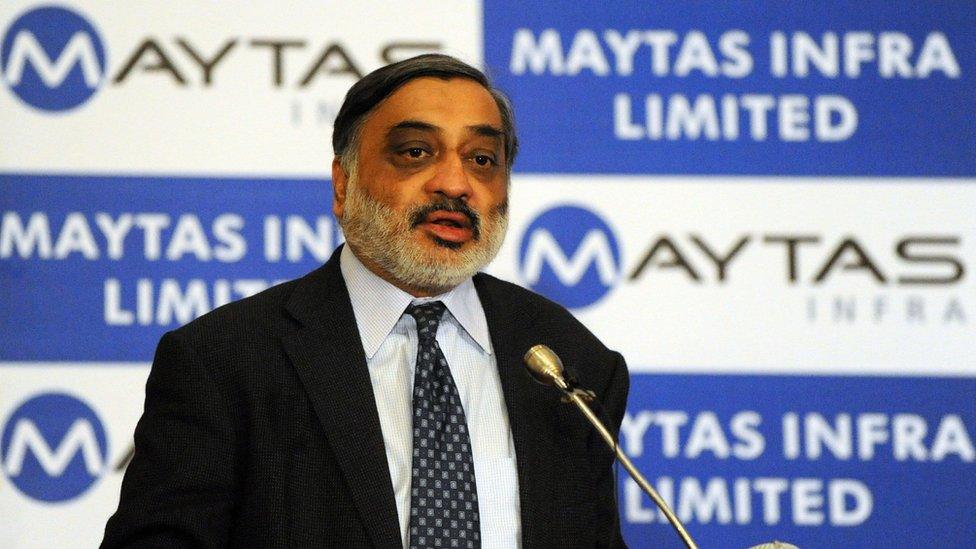

Chairman of IL&FS, Ravi Parthasarathy, has stepped down citing health reasons

But the storm has been brewing for a while.

Just three months ago, the first warning sign about the financial status of IL&FS was flashed when its chairman Ravi Parthasarathy stepped down after three decades, citing health reasons.

Then came the ratings downgrade.

In August, IL&FS found itself down from AAA to AA+ for loans and debentures. By the end of September, this rating was revised multiple times to junk status. Experts say the government could have moved in earlier.

"The government, regulators, board and auditors allowed this crisis to grow into this mess. There were warning signs but now deeper investigation will reveal why they were ignored. Hopefully, the lessons from this crisis will improve the level of regulation and governance," says analyst Pranjal Sharma.

IL&FS was designed to give financial and technical help for infrastructure projects

This is the second time in nine years the Indian government has taken control of a beleaguered firm.

In 2009 a corporate scandal in a leading Indian IT firm, Satyam, forced the ruling Congress party-led government at the time to step in.

This time, the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government is following in their footsteps: it has appointed a six-member board, which now includes banking and corporate governance veterans.

The board will restructure the firm and arrange fresh funds so that existing projects don't stop.

Also, a fraud investigation has been initiated to look into financial mismanagement.

"The main thing is to figure out what are the requirements for liquidity," said Mr Narayan, the former banker. "It is a complicated set-up. But the biggest challenge for the new board will be to come clean and be honest about the entire situation."

- Published15 February 2018

- Published19 February 2018