The Indian animal trainer who became a circus legend

- Published

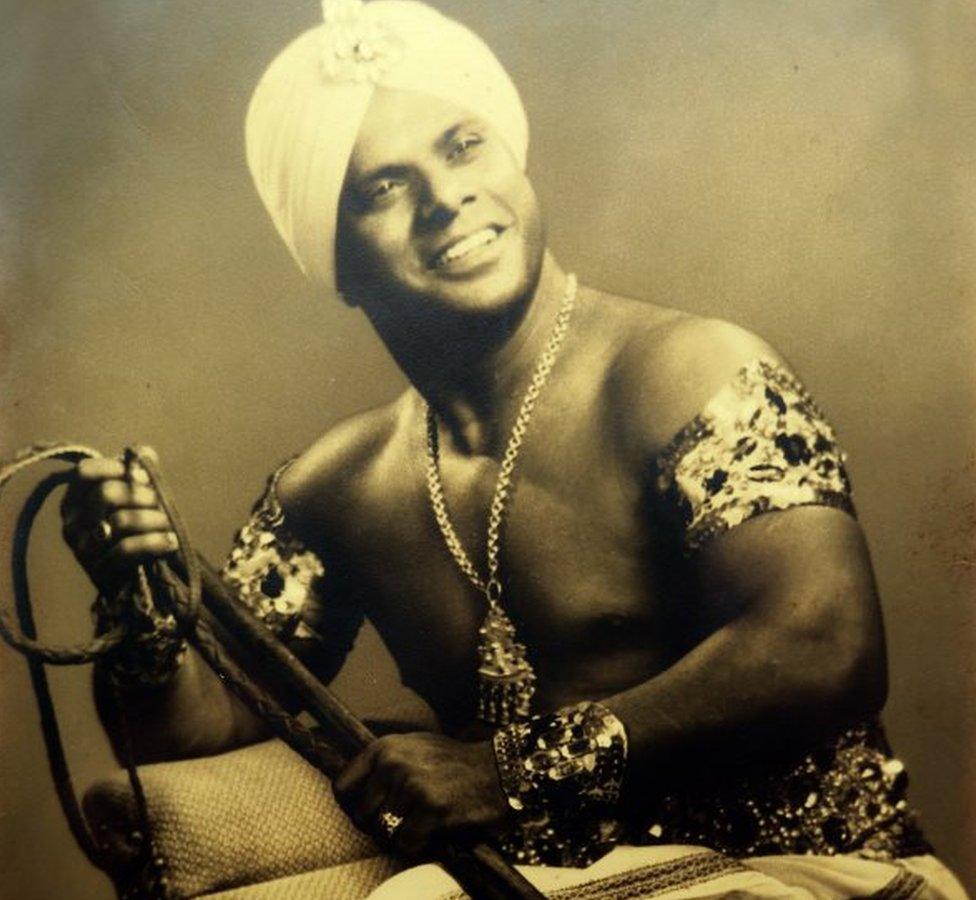

Damoo Dhotre was known for daredevil acts

During a circus performance in Shanghai in 1927, a writer stepped into a cage to interview a legendary animal trainer from India. They had five tigers and four leopards for company.

This was an extraordinary setting for an interview. But then nothing about Damoo Dhotre was ordinary.

Although only 25, he had already become famous for his daredevil circus acts. And he wanted the writer to observe first-hand how effortlessly he controlled wild animals.

Although Damoo went on to become one of the greats of the circus world, very little is known about him in India.

His grandson, Mahendra Dhotre, has researched his grandfather's life and wants young people to know about his achievements.

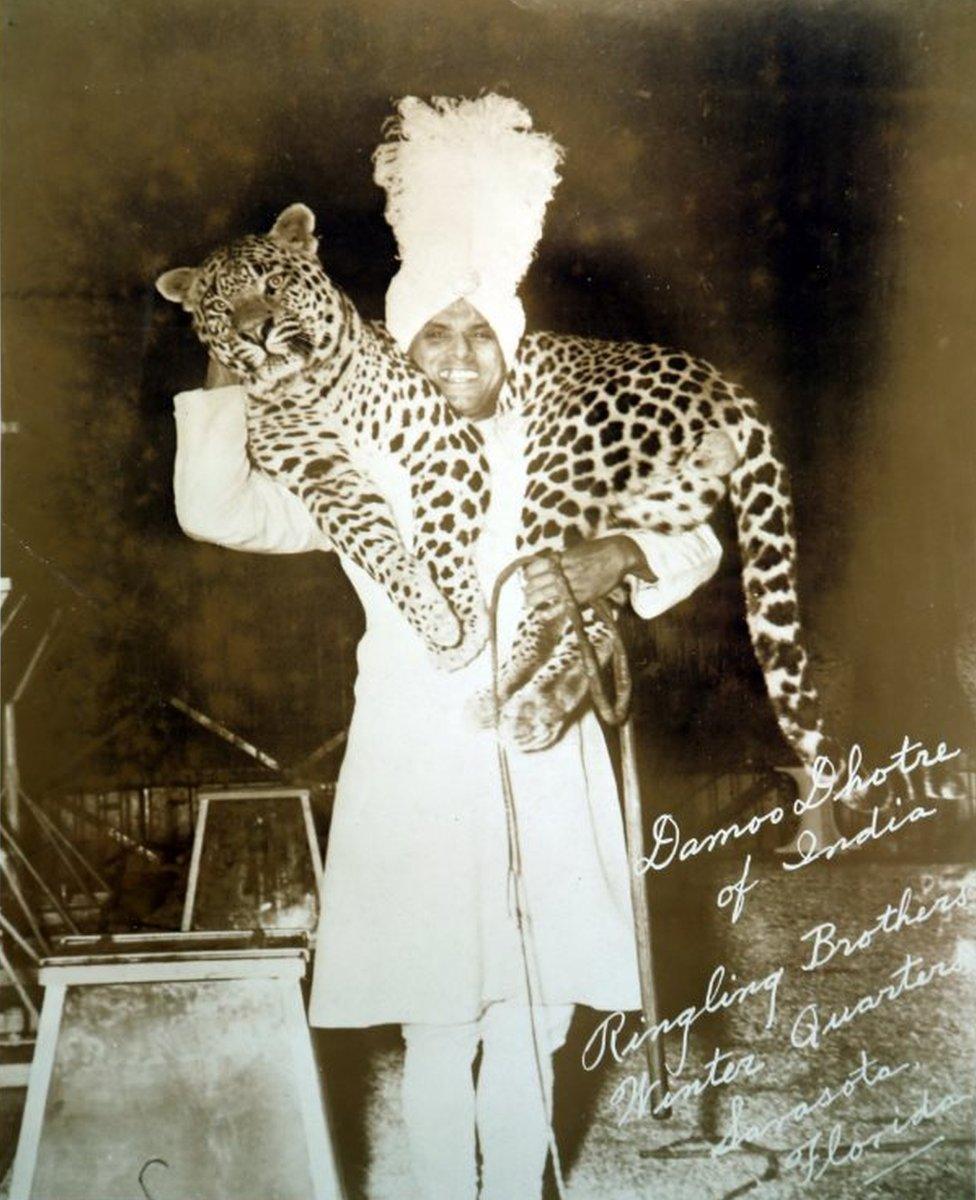

Damoo Dhotre won many awards during his career

"His story is remarkable," Mr Dhotre says. "He started his career in colonial India and became a legend at a time when it was difficult for a brown person to reach the top position in any profession."

Damoo was born in the western city of Pune in a middle-class family. He started visiting his maternal uncle's circus when he was only 10 years old.

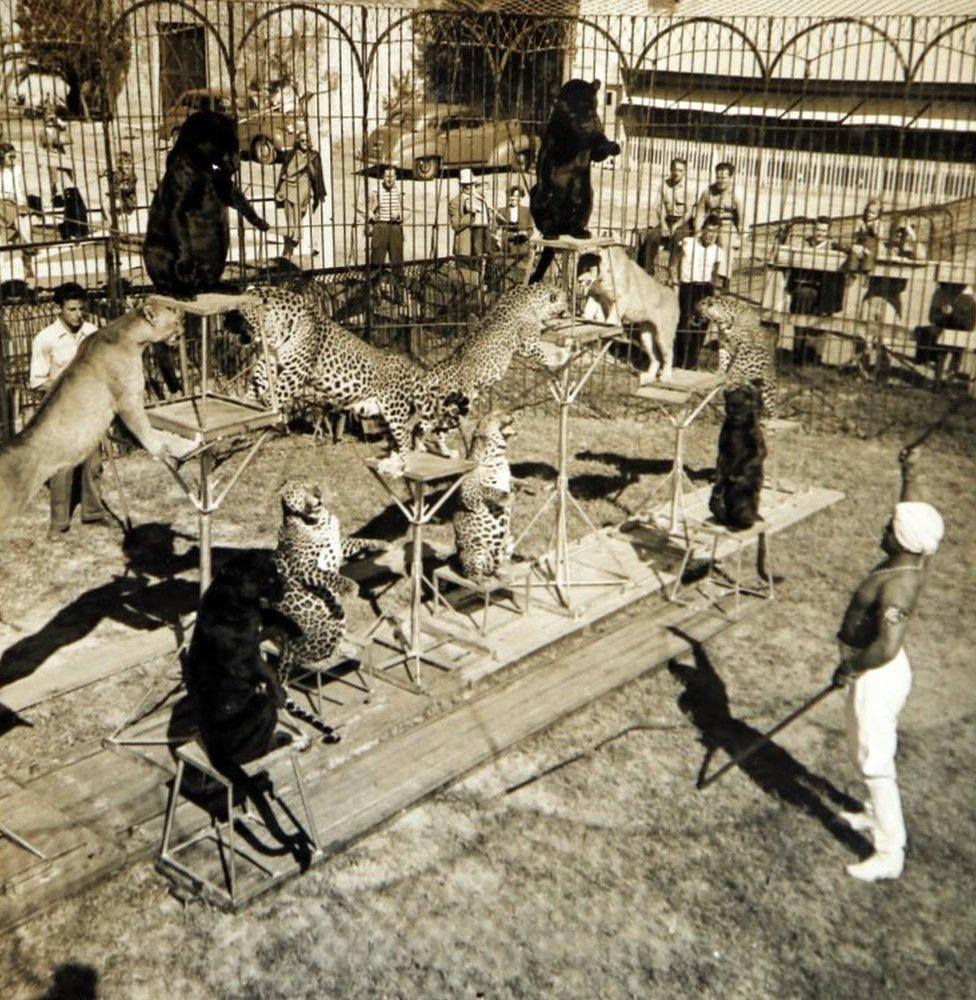

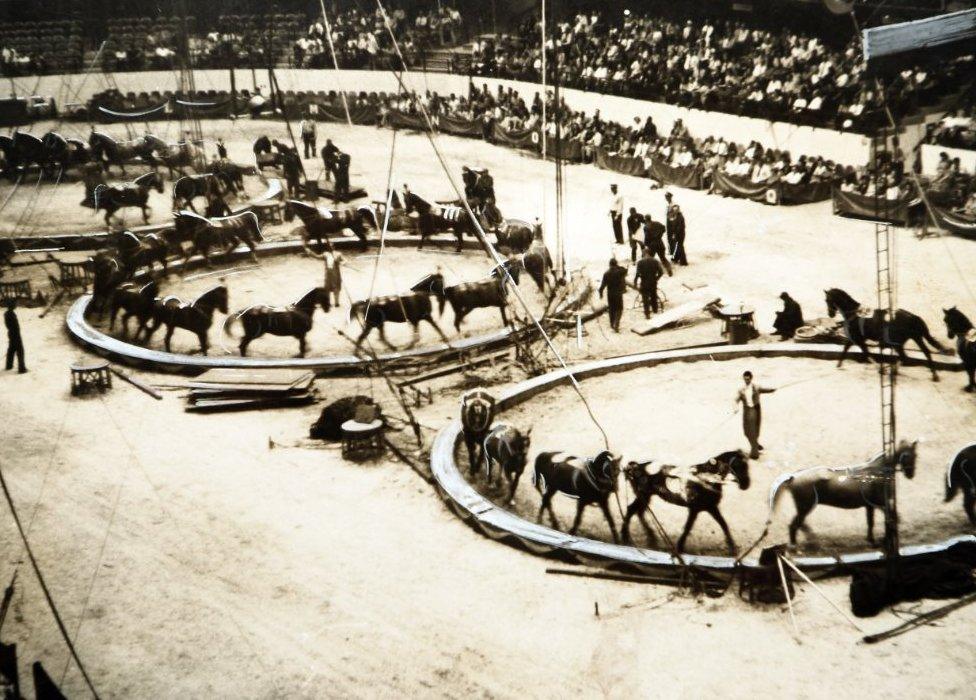

He was known for staging grand shows

He was fascinated with wild animals. He would observe the trainer closely and then he would mimic his routine outside the cage.

"One day the cage was open and he entered it and managed to keep the animals calm. It was only for a few minutes but everybody in the circus realised that he was special," says Mr Dhotre.

"This incident showed that he was fearless. He had this attitude throughout his career. He was fearless and brave, and used these attributes to create drama inside the ring."

Noticing Damoo's interest, his uncle agreed to train him. This angered Damoo's mother who was horrified at the thought of her son entering a cage that held wild animals.

She relented after her brother assured her Damoo would be safe. And that's how the legendary trainer Damoo Dhotre was born.

In 1912, Damoo dropped out of school and travelled with his uncle for the next four years. But he missed his mother and felt homesick. So, he returned to Pune.

His heart still belonged to the circus. He also wanted to earn money to help his parents.

"He started performing stunts on a bicycle. This made him popular and some local newspaper named him the 'boy wonder'," Mr Dhotre says.

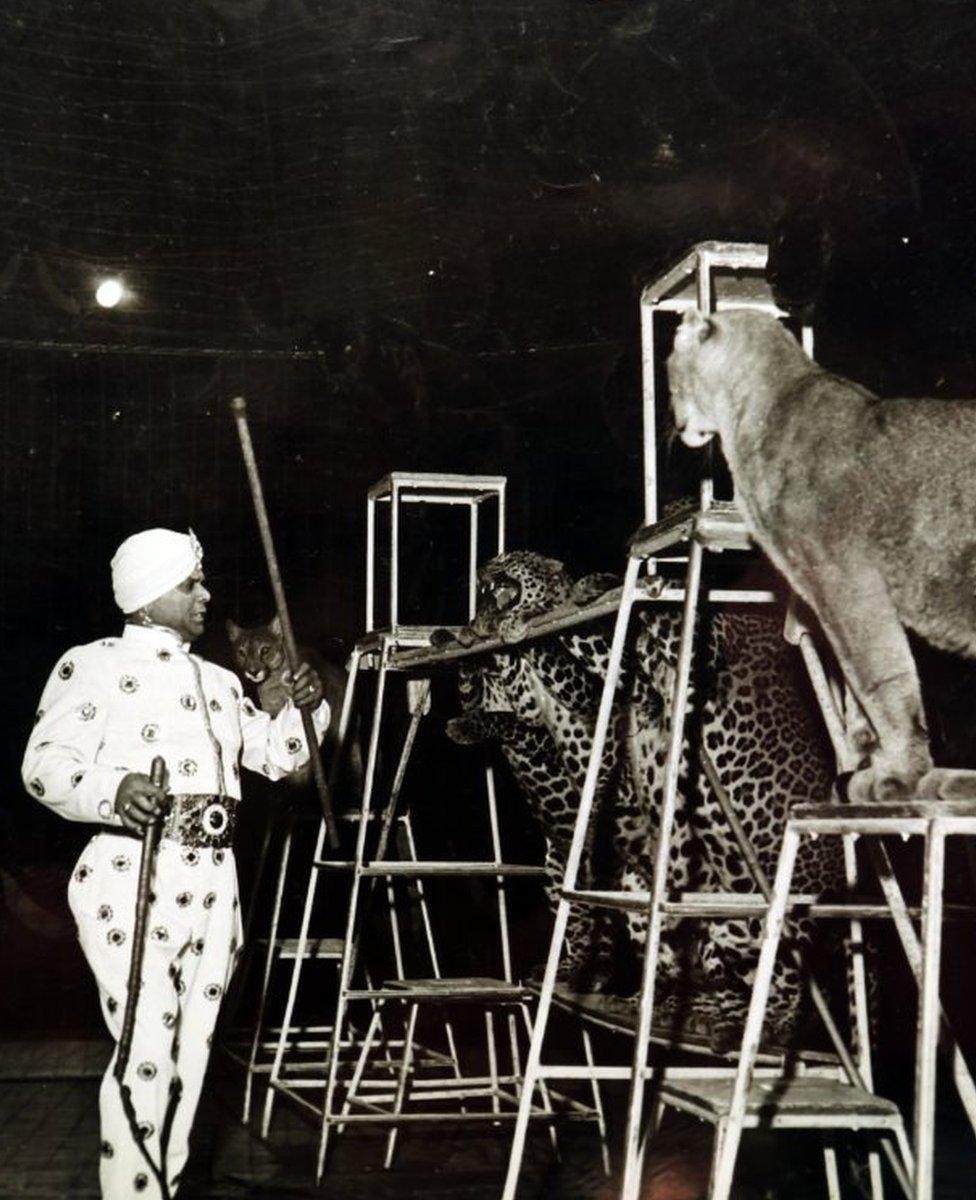

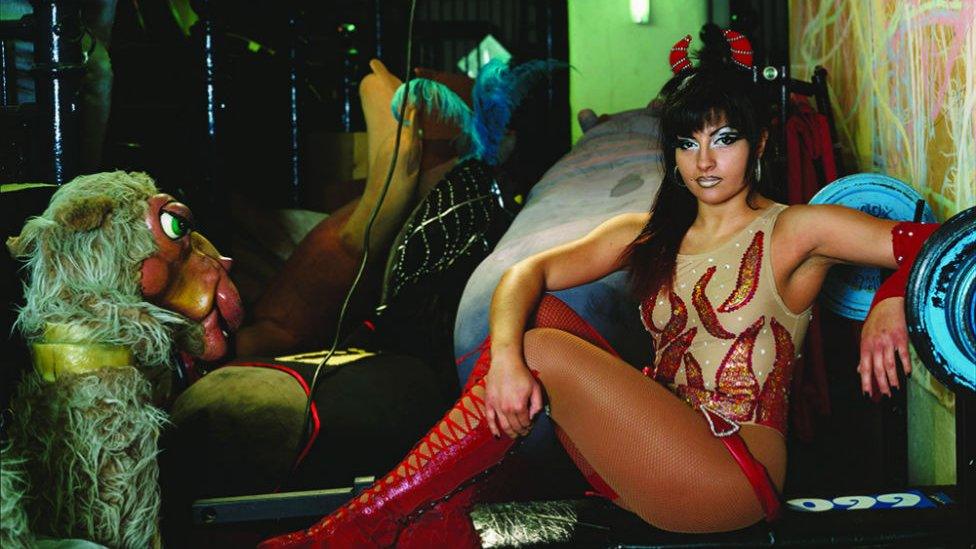

His acts were full of surprises

Damoo continued to perform stunts across Pune - he would also freelance as an animal trainer whenever he found the opportunity.

He was 22 when he applied for a job as a motorcycle stunt rider with a Russian circus. He got the job and convinced the owners to let him work as a ring master. His big moment came when he travelled to China with the circus.

"He was an instant hit in China," Mr Dhotre adds. "I think people liked his daring attitude. He could easily work with dozens of animals inside a cage."

The ringmaster's attire also drew crowds. Back then, people were used to seeing ring masters fully clothed and using protective gear. Damoo always entered the ring bare-chested, wearing a pagadi, the traditional Indian headgear.

He mostly performed bare chested

He was a master of creating drama inside the ring. One of his famous acts involved a goat riding on the back of a tiger. It almost defied logic because tigers and leopards typically prey on goats.

Mr Dhotre says this was possible only because of Damoo, who somehow managed to gain the trust of wild animals.

He could train and control many animals at the same time

Damoo was just 22 when he became a ring master

Despite his popularity, Damoo felt the Russian circus was too small for his ambitions. He decided to advertise in European newspapers. A French circus owner saw his ad and asked him to go to Europe.

He travelled to France in January 1939 but the journey cost him all the money he had earned.

When he arrived, he was relatively unknown in Europe. But it wasn't long before he became famous in France. He started earning well too.

"By this time he was married and had three sons. He started sending money back home and it made him very happy," Mr Dhotre says.

But his success didn't last long. World War Two had engulfed Europe by the middle of 1940 and soon circuses were banned because of the security risks.

Damoo was heartbroken, his grandson says.

"He was stuck alone in Europe and he was jobless. Those were difficult days for him."

Damoo worked for the renowned Ringling Brothers circus

Then the French circus decided to travel to the US, and invited Damoo to join them. He was excited because the US was home to Ringling Brothers circus - the biggest and most famous one at the time.

After reaching the US, he contacted officials at Ringling Brothers and asked them for a slot. He was hired and went on to become a huge hit.

"People in the US had not seen such fearless acts and they loved him. His place as a legend in the circus world was now cemented," Mr Dhotre says.

But the US entered the war in late 1941 and circuses were banned. Damoo was enlisted as a US army corporal, before rejoining the circus when the war ended in 1945.

He quit Ringling Brothers in 1949 due to ill health and went back to Europe. Two years later, he returned to India as his health worsened.

By then, his wife had been diagnosed with cancer. She died before he arrived home. He decided to take a break from the circus and, eventually, he quit because he had become asthmatic and could no longer work with animals.

"But he was too attached to the circus world. So he started to train and help others who wanted to become ring masters," Mr Dhotre says.

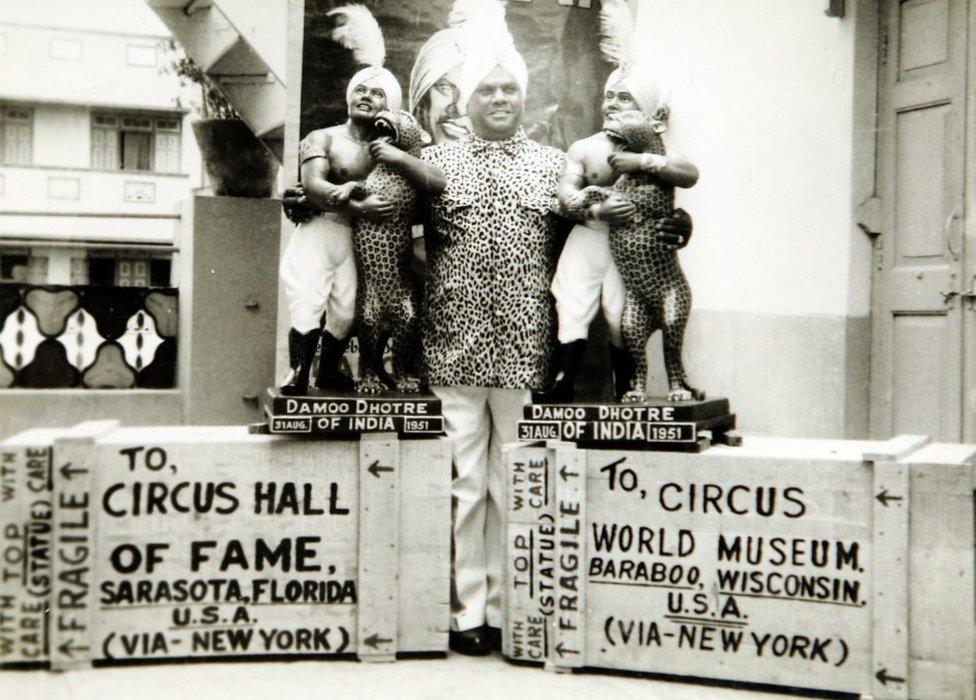

Damoo Dhotre is the only Indian to be inducted in the International Circus Hall of Fame

In 1971, Damoo was inducted into the International Circus Hall of Fame, external. He died two years later.

"Damoo's story is not widely known in India. There is a lot we can learn from him. He taught us that you can achieve anything if you believe in your dreams," Mr Dhotre says.

"There can't be another Damoo Dhotre because circus is a dying craft and the use of animals is now banned. So it's important to remember his legacy."

Mr Dhotre, however, agrees that some may consider Damoo's circus acts cruel.

"I think that in today's context the use of animals in circuses is cruel. But Damoo existed in another time when there weren't many sources of entertainment. He just followed his passion and became a legend and that's how I want people to remember him."

- Published2 September 2018

- Published4 February 2018

- Published22 May 2017

- Published12 February 2016