A kidnapped girl, a skeleton and a house of memories

- Published

Navaruna Chakravarty was kidnapped in September 2012

Six years ago, a 12-year-old schoolgirl was abducted from her bedroom in the eastern Indian state of Bihar in the middle of the night. The unusual case prompted the country's top court to order federal detectives to take over the probe, but they have drawn a blank. So why do her parents still believe she is alive?

He sleepily shuffled to the verandah and looked outside. It was pitch black.

Atulya Chakravarty had woken up in the middle of a rainy night to use the toilet. The two energy efficient fluorescent light bulbs that always lit up the courtyard at night to keep out burglars were not burning.

That is unusual, he thought to himself.

He returned to the bedroom, woke up his wife, Moitri, and asked her whether she had forgotten to switch them on before going to bed. She mumbled she hadn't, pushed off the quilt and climbed out of bed.

The couple stepped out onto the verandah which ran alongside two bedrooms on the ground floor of their squat two-storied house in the city of Muzaffarpur.

Now, lit by torchlight, what they saw sent chills down their spine.

The two doors in the closed verandah that overlooked the courtyard were ajar. Fear woke them up completely.

The panicked mother ran into the adjoining bedroom where their 12-year-old daughter Navaruna had gone to sleep.

Navaruna was kidnapped from her bedroom

The frail and shy girl had spent the day at home. She had applied henna on her hands, watched cartoons on TV and had bread and milk for dinner before calling it a night.

The lights went on. A tidily arranged silk shawl, a crumpled pillow and the mosquito net on the antique bed were in their place. But the bed itself was empty.

"She's not here, she's not here!" Mrs Chakravarty screamed into the night.

Navaruna Chakravarty disappeared on the night of 18 September 2012, a Tuesday. Or was it in the wee hours of 19 September?

The girl 'vanishes'

Investigators believe at least one person wriggled into her room after wrenching open the rotting iron bars of her bedroom window - it overlooked a dingy lane that was the main path used to access the house.

He had possibly gagged and sedated the sleeping girl. Woken up violently, she had urinated in fright, leaving a wet patch on the sheets. Then he had carried her out to the verandah.

Investigators believe the abductor opened the two doors from inside the house to let more people in. They had helped carry the girl out through an opening in the back of the house - the front door was locked from inside.

There was a vehicle waiting on the main road, a few yards away. The girl and her abductors vanished into the drizzly night.

Police believe a dispute over selling the house where the family lives led to the kidnapping

Navaruna's parents believe she's still alive and her captors are at large. Investigators believe she's dead but concede the captors are still roaming free.

A month after the incident, police arrested three men, including a distant, estranged relative of the Chakravartys.

The police said the three "seemed that they were hiding something", but found nothing incriminating to implicate them in the crime. They were released after nine months in prison.

On 26 November, local people found some skeletal remains in a neatly wrapped plastic bag in a fetid open drain close to the Chakravarty home. The family remembers there was some commotion, as municipal workers came, took out the bag and handed it over to the police.

Bone examination

Later that day, police told the family that they had found their daughter's bones. The parents refused to believe them and asked: Where's the evidence?

The following month, a state hospital carried out a forensic examination of the bones "attached to decomposed muscles and tissues" - a collarbone, a long upper arm long bone, bits of femur and tibia.

Doctors took away a molar tooth, a rib, a part of the thoracic vertebrae - a group of a dozen small bones that form the vertebral spine in the upper trunk - and some decomposed thigh muscles for DNA tests.

The examiner concluded that the bones "are of human in nature and belong to an individual, of a female, about 13-15 years of age who died 10 to 20 days before the date of receiving" the remains. The cause of death "could not be ascertained". The examiner said clothes found on "the decomposed body are suggestive of [a] teenage female".

The forensic doctor had examined a few bones - and certainly not a body - that arrived in a small box. The box also contained a black top, orange-and-white striped underwear and a black skirt, which the "body" was apparently wearing.

Navaruna's rubber sandals still lie on the floor in her room

The Chakravartys have always believed that the bones do not belong to their daughter, and that the bag was "planted" in the drain. They agreed to DNA tests in 2014, but they say the results have not been shared with them.

"If the bones are indeed of my daughter, why are investigators not sharing the results of the DNA tests?" wonders Mr Chakravarty.

The federal crime fighting agency, the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI), which took over the probe in 2014, said what had happened was a "blind kidnapping-cum-murder case". And the motive appeared to be a feud over the house in which the family has lived for decades, and from where Navaruna was taken away in the middle of the night.

Lawless city

Muzaffarpur, a teeming, exhausted city in one of India's poorest states, is known for cheap clothes, lacquered bangles and gangsters. Murders and abductions for ransom are common. Many are over plots which rival "land mafias", as they are called here, try to grab or buy cheap using coercion and fear. The streets are filled with dread for unescorted women who say they are stalked and harassed by men with impunity.

The Chakravartys had been long planning to sell their century-old tumbledown house in a congested but prime neighbourhood and move out of the city. Mr Chakravarty, now 66, is a retired pharmaceutical sales representative.

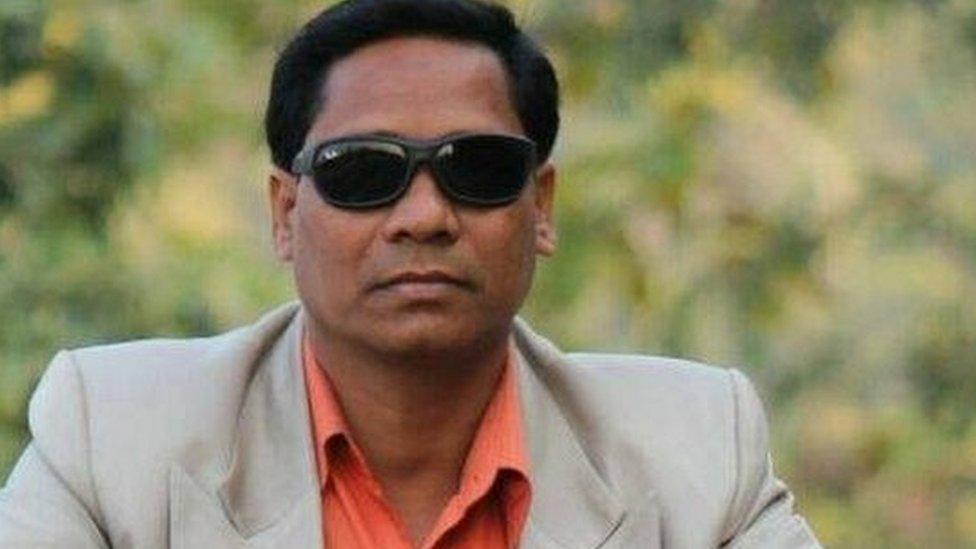

Atulya Chakravarty has spent the last six years waiting for his daughter

A fortnight before the kidnapping, he had signed an agreement to sell his property - the six-room house, a courtyard filled with palm, coconut and guava trees, a disused well and a small outhouse - for some 30 million rupees ($410,000; £320,000) to a local realtor, and accepted an advance of a little more than two million rupees.

As word of the impending sale swirled around the town, Mr Chakravarty says he came under pressure to cancel the deal and sell the house to a rival realtor. Even local policemen came home and asked him, he says, to cancel the deal.

"It was clear that the local police was in cahoots with a gang that wanted me to cancel the deal and sell it to another party. I was holding out. Then my daughter disappeared."

With her abduction, the house effectively became a crime scene, and the process of selling it ground to a halt.

The cupboards in the room are filled with Navaruna's dolls

Over the next few years, police questioned Navaruna's family, relatives, friends and teachers. They searched the Chakravarty residence, and took away two of her diaries. One, according to the police, had some photographs and stickers, while in another she had apparently "written about the qualities of a Dream Boy" without naming him. (They were clearly pursuing an unsuccessful "elopement" angle at the time.) They even inspected a septic tank in her house to check for any human remains, to rule out an "honour killing".

Teams fanned all over India, keeping an eye on crowded bus stands and railway stations. Police even staked out a hostel in Delhi where the couple's eldest daughter lived.

'Police involvement'

Mobile phone records of at least 100 people, including the family and the original suspects, were examined. Data from hundreds of thousands of phones from mobile towers of half a dozen telecom providers were examined for chatter in the neighbourhood on the night of the kidnapping. Raids were conducted at various places, including a local red-light district, to rule out trafficking.

"We have made sincere efforts to track down Navaruna. We have made intense examinations. We have carried out scientific investigations," the police told the court. The investigation clearly appeared to have hit the buffers.

Last month, the CBI told the Supreme Court that it had arrested six more suspects in April, questioned them for eight days and remanded them to judicial custody for 90 days before the court released them on bail. They had searched their homes and offices and found nothing suspicious.

Navaruna rode to her convent school on a pink bicycle

But in a significant twist, the sleuth agency said it had questioned three senior police officers who were directly connected with the investigation when the incident happened.

In a report submitted to the top court last month, the agency said the first investigating officer and the head of the Muzaffarpur police station "have to go through narco tests and brain mapping test".

"Truth drug" test results have never been admissible in Indian courts but police say they have provided leads. In the tests, a suspect is injected with sodium penthanol, a chemical that numbs powers of perception and supposedly makes it difficult for a person to lie during questioning.

'Don't play games'

The agency also spoke about the "deceptive response" of the main policemen investigating the case, and pledged to explore the "bureaucrat-mafia nexus" in the crime.

Waiting for their daughter has taken a grim toll on the Chakravarty family. A heart patient, Mr Chakravarty nearly overdosed on sleeping pills after spending sleepless nights waiting for his daughter.

Every day, for two years after the incident, Mrs Chakravarty would visit the local police station and demand answers from the officer in charge.

"Don't play games with me," she would tell the policemen. "Give me my daughter back."

Over the years, Mr Chakravarty has turned from a grieving father to an angry, obsessive detective, trying to find clues about Navaruna's disappearance.

Moitri Chakravarty believes her daughter is alive and will return soon

He has recorded four gigabytes of phone conversations with police officials on his mobile phones and "mysterious calls" he says he received from different parts of India until a month after his daughter's disappearance.

"I even heard my daughter's muffled voice in some of them," he says.

In his clear handwriting and in finely-vivid detail, he has written five exhaustive diaries, detailing his conversations with investigators. He's begun writing a book on the case, and has already completed 170 pages. He has written letters to politicians, judges, and the prime minister and president of India. He has personally visited the state's chief minister Nitish Kumar and complained about the snail-paced investigation.

He reads aloud obsessively from the diaries, almost enacting the scenes and intoning the voice of the detectives, as if to tell the world: "Listen to me. I know who's behind the kidnapping. Why is no one taking me seriously?"

More from Soutik

All this is triggered, says Mr Chakravarty, by a sense of guilt, grief and vengeance. There's guilt over his failure to protect his daughter; grief at her prolonged disappearance and vengeance "against the system which conspires to delay justice to common people".

"How can I go on living here like this," says Moitri Chakravarty. "How long can you live in this house of memories? When she returns home, we will leave the place."

The crumbling house is an oppressive museum of memories, carrying the full weight of darkness and tragedy. The Chakravartys seem to have even stopped cleaning the room that Navaruna spent most her time in, lest a speck of memory vanishes with the dust.

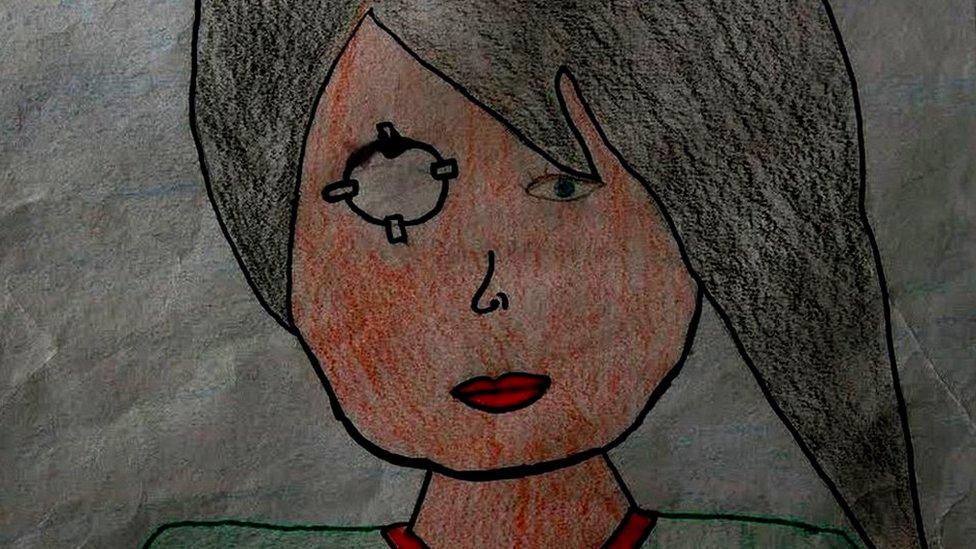

Navaruna's drawing books are full of pictures

"Navaruna is everywhere, around us. Just look around and you will feel her presence," says Mrs Chakravarty.

Her school uniform - the maroon tie and skirt, the white cap - is packed inside a string basket which hangs on the wall outside. Her maroon cotton towel, now mouldy with age, hangs outside the door, untouched since she disappeared. In a corner stands a pink cycle which her father bought for her 20-minute ride to the convent school.

In the room, a glazed-glass cupboard is full of the missing girl's possessions. Plastic dolls gaze eerily through the dust. A small red purse with 200 rupees lies in a corner. The printed school schedule is pasted behind the door. A folded study table lies in a corner. In the room where she went missing, her pink dress hangs on a fraying clothesline; a white vest is strung up near the main door.

On the dressing table she shared with her mother, her tube of moisturizer is untouched. On her father's table, which she would sometimes use, there's a faded pink whistle, painting books with drawings of young girls and cartoon characters. And there are strips of medicine tablets that her father takes every day to keep his blood pressure in control and protect his heart.

Navaruna's pink dress still hangs in the room

It is a house of suffering and pain.

"Navaruna is coming back. So we have kept her things in place", Ms Chakravarty says, welling up.

"She's 18 now. I wonder how she looks."

Related topics

- Published5 May 2018

- Published12 October 2018

- Published29 May 2017