The man who spent decades befriending isolated Sentinelese tribe

- Published

A photograph of Mr Pandit handing a coconut to a Sentinelese man in 1991

Not many people know more about the Sentinelese than Indian anthropologist T N Pandit.

As a regional head for India's Ministry of Tribal Affairs, Mr Pandit embarked on visits to their isolated island community over a period spanning decades.

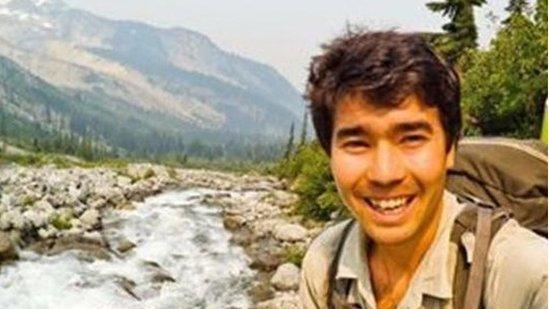

The tribe, who have lived in near-total isolation for tens of thousands of years, came to global attention last week after they reportedly killed a 27-year-old American would-be missionary trying to make contact with them.

But Mr Pandit, now 84, says from his experience the group are largely "peace-loving" and believes their fearsome reputation is unfair.

"During our interactions they threatened us but it never reached a point where they went on to kill or wound. Whenever they got agitated we stepped back," he told the BBC's World Service.

"I feel very sad for the death of this young man who came all the way from America. But he made a mistake. He had enough chance to save himself. But he persisted and paid with his life."

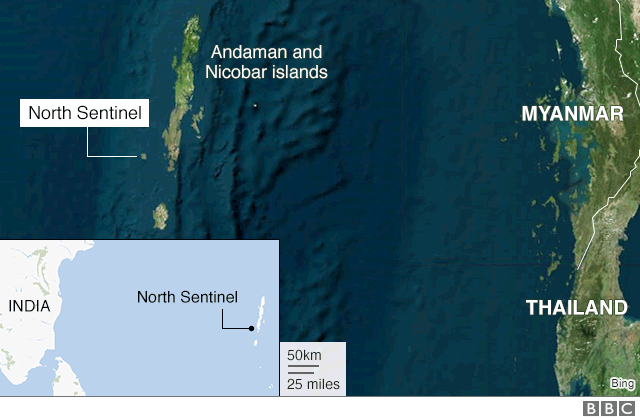

Mr Pandit first set out to visit North Sentinel island, solely inhabited by the tribe, in 1967 as part of an expedition group.

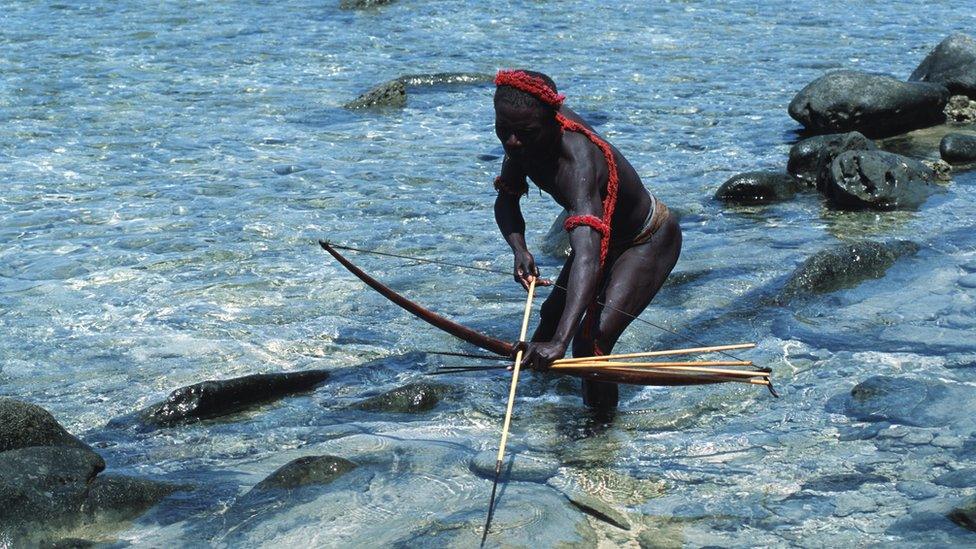

Initially the Sentinelese hid in the jungle from their visitors, and then on later trips shot at them with arrows.

He said the anthropologists would bring a selection of items along with them on their trips to try and entice contact.

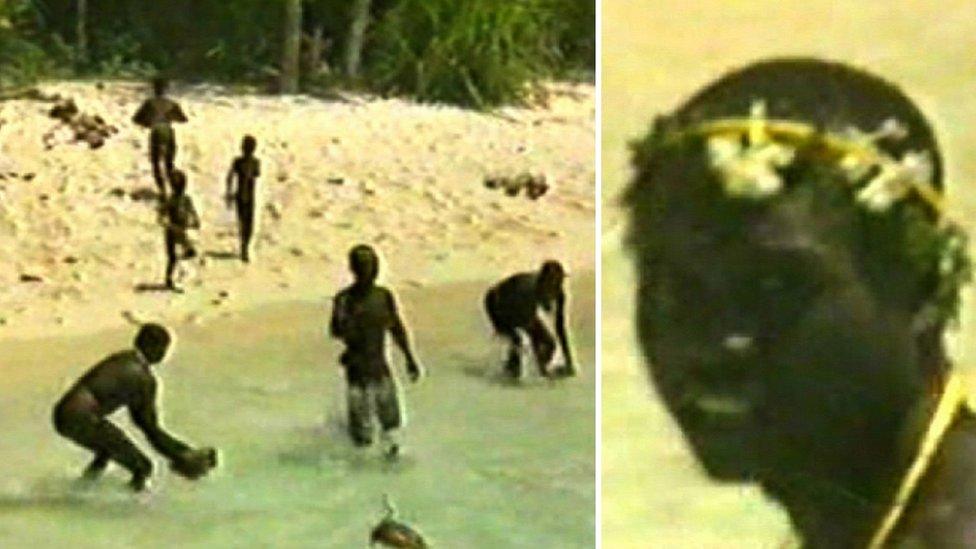

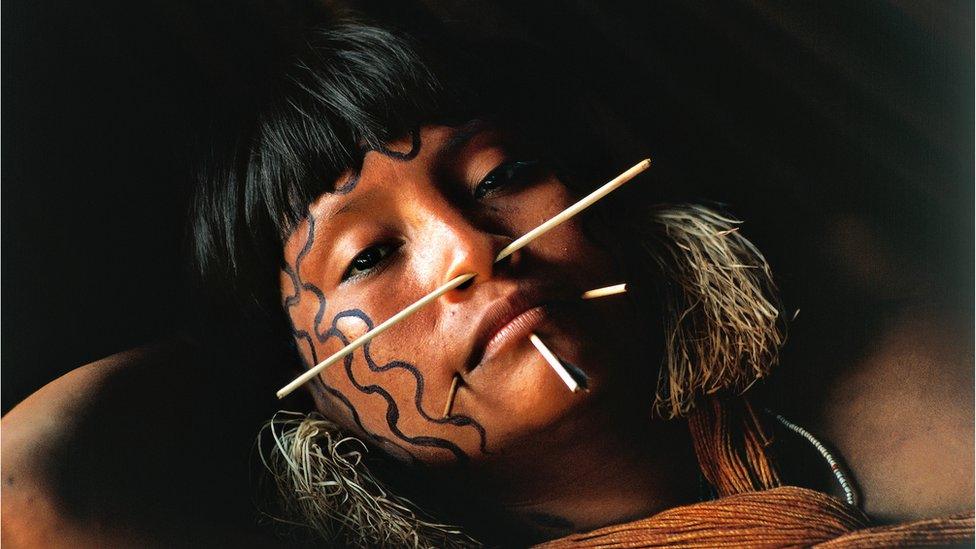

Few images of the endangered tribe exist

"We had brought in gifts of pots and pans, large quantities of coconuts, iron tools like hammers and long knives. We had also taken along with us three Onge men (another local tribe) to help us 'interpret' the Sentinelese speech and behaviour," he recalled in an essay charting his visits.

"But the Sentinelese warriors faced us with angry and grim faces and fully armed with their long bows and arrows, all set to defend their land."

Despite little success, they would leave gifts behind to try and build rapport with the mysterious community.

In one instance, he said they knew a tied-up live pig they offered was clearly unappreciated by the group when they swiftly speared the animal to death and buried it in the sand.

Making contact

After several expeditions trying to establish contact, their first real breakthrough came in 1991 when the tribe came out to peacefully approach them in the ocean.

"We were puzzled why they allowed us," he said. "It was their decision to meet us and the meeting took place on their terms."

"We jumped out of the boat and stood in neck-deep water, distributing coconuts and other gifts. But we were not allowed to step onto their island."

Mr Pandit (right) worked for India's Ministry for Tribal Affairs

Mr Pandit says he was not overly worried about being attacked, but was always cautious when he was in close proximity with them.

He says their team members tried to communicate in sign language with the Sentinelese, but had no success as they were largely pre-occupied with their gifts.

"They were talking among themselves but we couldn't understand their language. It sounded similar to the languages spoken by the other tribal groups in the area," Mr Pandit recalled.

'Not welcome'

In one memorably tense exchange on the trip, one young member of the tribe threatened him.

"When I was giving away the coconuts, I got a bit separated from the rest of my team and started going close to the shore," he told the BBC.

"One young Sentinel boy made a funny face, took his knife and signalled to me that he would cut off my head. I immediately called for the boat and made a quick retreat,"

"The gesture of the boy is significant. He made it clear I was not welcome."

Who are the Sentinelese?

The Indian government has since abandoned gift-giving expeditions, and outsiders are banned from even approaching the island.

The complete isolation of the Sentinelese people means any contact with the outside could put them at deadly risk of disease because they are likely to have no immunity to even common illnesses such as flu and measles.

Mr Pandit said members of his groups were always pre-screened for possible communicable diseases and only those in good health were allowed to travel to North Sentinel.

Officials say Chau, who was killed last week, did not gain any official permission for his trip.

He is instead said to have paid local fisherman 25,000 rupees ($354; £275) to take him to the island illegally in the hope of converting the tribe to Christianity.

An effort is now underway to try and retrieve the American's body - something Mr Pandit has suggested could be possible with a tentative approach by officials, external.

Despite his own experience of tense exchanges with the Sentinelese, Mr Pandit resists labelling them as hostile.

"That is the incorrect way to look at it. We are the aggressors here," he told the Indian Express. "We are the ones trying to enter their territory."

"Sentinelese are a peace-loving people. They don't seek to attack people. They don't visit nearby areas and cause trouble. This is a rare incident," he told the BBC.

Mr Pandit says he does favour the re-establishment of friendly gift-dropping missions with the tribe, but says they should not be disturbed.

"We should respect their wish to be left alone," he said.

That view is shared by conservation groups such as Survival International, who have implored local officials to abandon attempts to retrieve Chau's body.

Read more on uncontacted tribes:

- Published26 November 2018

- Published21 November 2018

- Published24 November 2018

- Published23 November 2018