Finding God in the anguish of violence

- Published

As violence has intensified in Indian-administered Kashmir, people have been flocking to the region's fabled Sufi shrines in search of solace. Sameer Yasir speaks to photographer Azan Shah, who has been documenting the anguish of the devotees.

Bakhti Begam is a regular at Khanqah-e-Moula, a Muslim Sufi shrine located on the banks of river Jhelum, which careens through the heart of Srinagar city.

She arrives quietly, holding a framed photograph of her missing son in a torn plastic bag. She places it on the stairs leading to the sanctum sanctorum and prays to be united with him.

"Please listen to me, my peer [saint]. I am broken, my peer," the 75-year-old cries with folded hands. Her son, Manzoor Ahmad Wani, who was 25 at the time, disappeared on 22 December, 2001, a few days after he got married.

Bakhti Begam regularly makes the 80km (50-mile) trip to the shrine from her home. But her prayers are yet to be answered.

"I have come from far away, my peer. Please give me my Manzoor. I will sleep peacefully after 17 years," she laments.

Bakhti Begam is just one of the many characters featured in the works of photographer Azan Shah.

Mr Shah came into the limelight when his pictures were published in a book called Witness along with a number of other photojournalists who have worked in the state during decades of conflict. The book was among the 10 best photo books of 2017 chosen by the New York Times.

Separatists have waged a violent campaign against Indian rule in Muslim-majority Kashmir since 1989. The region remains a subject of bitter dispute between India and Pakistan, who have fought two of their three wars over it. India has long accused Pakistan of fuelling the unrest, a charge Islamabad denies.

The insurgency, which had begun to wane since the late 1990s, intensified in 2016 after forces shot dead popular militant leader Burhan Wani.

Human rights organisations estimate that about 100,000 people have died as a result of the violence since the 1980s, many of them civilians. As a result, fear dominates the streets and few venture out after dusk.

Many find salvation in Sufi shrines to heal the wounds of war - not just in Srinagar, but even in remote areas of the region.

Like Bakhti Begam, there are thousands of Kashmiris, particularly women, for whom Sufi shrines have long been places of hope. Many of them, psychiatrists say, show symptoms of depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Maroofa Ramzan is among them. Every week she meets a psychiatrist at Srinagar's Shri Maharaja Hari Singh Hospital. Her mental health has worsened in recent years after the death of her son. In the darkness, she claims to hear the voice of her son, Abir Ahmad, laughing and talking. He was shot dead by the army in 2010 during a protest.

After consulting the doctor, Maroofa Ramzan takes a bus to the Dastgeer Sahib, a 200-year-old shrine.

"He is alive, isn't he," she asks the Sufi saint at the shrine. Then, after some time, she slowly moves towards the gate and waits for the bus that will take her home.

A survey by Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) in 2016 found nearly 1.8 million people, translating to roughly 45% of the population in Indian-administered Kashmir, suffering from similar symptoms.

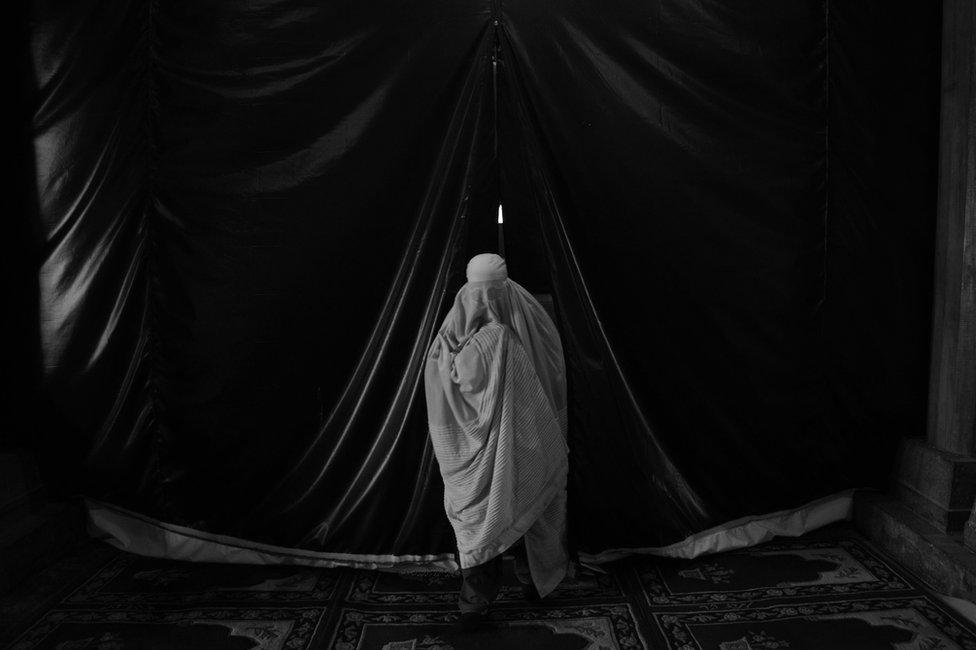

Azan Shah's pictures of devotees to Sufi shrines, all of whom have their own stories of pain and loss because of the violence in Kashmir, are intentionally blurred, shaky or tilted to give a sense of chaos and uncertainty in the moment.

Mr Shah says he tries to capture the unflinching faith of thousands of devotees who converge at these shrines.

"I prefer a tilted angle because it creates a psychological uneasiness. Things feel off-kilter, unsteady and unusual," he says, adding that he tries to convey the fact that "you can't control peoples' emotions".

"People find a mediator between God and themselves in these shrines," says Showkat Hussain, a professor of Islamic Studies at the Islamic University of Science and Technology, who has written on mysticism in Kashmir.

Arshad Hussain, a leading psychiatrist based in the region, adds that in Kashmir, these spiritual spaces serve as institutions of distress alleviation. "They started in times when there was no institution [to help] or redressal mechanism. Then it became a culture. People with sickness and domestic issues would end up in shrines with their pleas.

"In the current situation, after a conflict, many distressed women after paying me a visit end up in these shrines. They feel better talking about distress in spiritual spaces than to an individual."

All photographs by Azaan Shah