A holiday camp for India's captive elephants

- Published

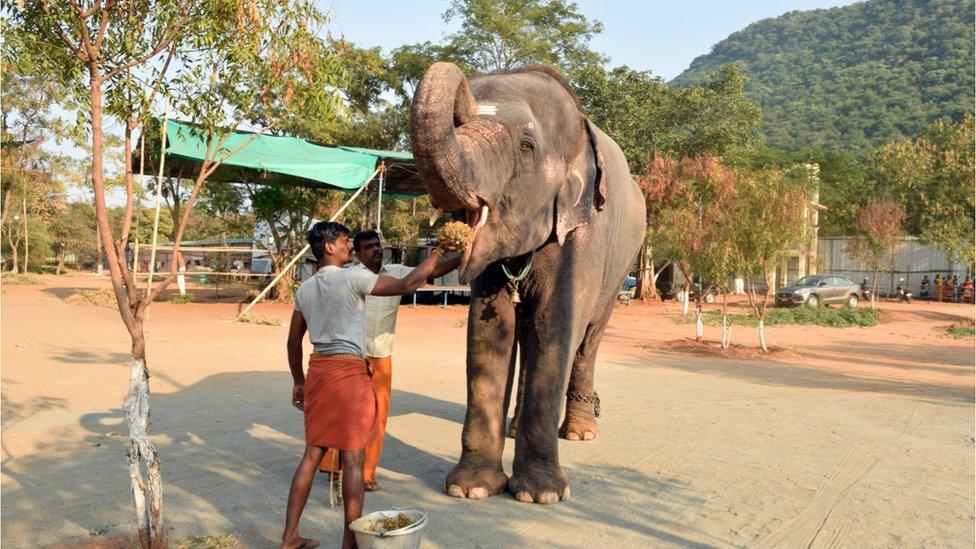

Arjun, the caretaker, pictured above with temple elephant, Akila

Once a year, some of India's captive elephants are whisked off to a "rejuvenation camp", where they are pampered and cared for by their caretakers. Omkar Khandekar visited one such retreat in the southern state of Tamil Nadu.

After seven years of being a local celebrity, Akila the elephant knows how to pose for a selfie. She looks at the camera, raises her trunk and holds still when the flash goes off.

It can get tiring, especially when there are hundreds of requests every day.

Despite this, Akila, performs her daily duties diligently at the Jambukeswarar temple. These include blessing devotees, fetching water for rituals in which idols of the deity are bathed, and leading temple processions around the city, decked up in ceremonial finery.

And, of course, the selfies.

But every December, she gets to take a break.

"When the truck rolls in, I don't even have to ask her to hop in," Akila's caretaker B Arjun said. "Soon, she will be with her friends."

Elephants sold to temples in Tamil Nadu are brought to this camp every year

India is home to some 27,000 wild elephants. A further 2,500 elephants are held in captivity across the states of Assam, Kerala, Rajasthan and Tamil Nadu.

The country is widely believed to be the "birthplace of taming elephants for use by humans". Elephants here have been held in captive by Indians for millennia. But 17 years ago, after protests by animal rights activists over instances of handlers abusing and starving captive elephants, the government stepped in to give the animals a bit of respite.

As a result, Akila and numerous other elephants held in temples around India are now brought to a "rejuvenation camp" each year, their caretakers in tow. For several weeks, the animals unwind in a sprawling six-acre clearing in a forest at the foothills of Nilgiris, part of the country's Western Ghats.

India has more than 2,000 captive elephants

The camps were described as an animal welfare initiative and have become a popular annual event for the state's temple elephants.

The one Akila and 27 other elephants are attending currently opened on 15 December last year, and will go on until 31 January, costing about $200,000 (£153,960) to run.

Supporters argue it is money well spent. A break from the city for these elephants is therapeutic, explains S Selvaraj, a forest officer in the area.

"Wild elephants live in herds of up to 35 members but there's only one elephant in a temple," he says. "For 48 days here, they get to be around their own kind and have a normal life."

It costs about $200,000 to run the six-week annual camp

Akila, who is 16 years old, has been a regular at the camp since 2012, the year she was sold to the temple. Arjun, who has accompanied her every year, is a fourth-generation elephant caretaker.

At the camp, he bathes Akila twice a day, feeds her a special mix of grains, fruits and vegetables mixed with vitamin supplements and takes her for a walk around the grounds. A team of vets are on hand to monitor the health of the camp's large guests, while at the same time tutoring their handlers in subjects like elephant diet and exercise regimes.

Akila has even forged a friendship with Andal, an older elephant from another temple in the state, said Arjun.

But despite the shady trees and quiet, the getaway is a far cry from an elephant's "normal life".

The government initiated such camps after protests over instances of handlers abusing captive elephants

The walled campus has eight watchtowers and a 1.5km (0.93 miles) electric fence around its perimeter. While the elephants appear well cared for, they spend most of their time in chains and are kept under the close eye of their caretakers.

And one six-week rejuvenation camp a year does little to assuage the stress of temple elephants' everyday lives, activists say.

"Elephants belong in jungles, not temples. A six-week 'rejuvenation camp' is like being let out on parole while being sentenced for life imprisonment," argues Sunish Subramanian, of the Plant and Animals Welfare Society in the western city of Mumbai.

"Even at these camps, the animals are kept in chains and often in unhygienic conditions," he adds. "If you must continue with the tradition, temple elephants should be kept in the camps for most of the year - in much better conditions - and taken to the temples only during festivals."

The camps have been described as an animal welfare initiative

Even among the company of their own, the elephants - like Andal and Akila - aren't allowed to get too close.

"I have to make sure the two keep their distance - otherwise, it'll be difficult to separate them when we go back," Arjun explains.

It is not just the animal rights activists who have concerns, however.

The camp has become a tourist spot in recent years, attracting a steady stream of visitors from neighbouring villages. Most watch, wide-eyed, from the barricades. But not everyone outside the camp is happy.

In 2018, a farmers' union representing 23 villages nearby, petitioned a court to relocate the camp elsewhere. The petition claimed that the scent of the animals - all female, as is the norm among temple elephants - attracted male elephants from the wild.

This has caused them to go on the rampage, often destroying crops that farmers depend on for their livelihood. The union says 16 people have died in such incidents.

The camp has also become a popular tourist spot in recent years

But the court rejected the petition, external. Instead, it asked why there were human settlements in what was identified as an elephant corridor. It also criticised the state government's tokenism of rejuvenation camps.

"Some day," it said, "this court is going to ban the practice of keeping elephants in temples."

But Arjun can't bear the thought of parting with Akila.

"I love her like my mother," he says. "She feeds my family, just like my mother used to. Without her, I don't know what to do."

But he also understands that his elephant can get lonely. "And that's why I work twice as hard to make sure she doesn't."

You may also be interested in:

The Indian man who runs an 'orphanage' for wild animals

All photographs by Omkar Khandekar

- Published24 April 2018

- Published7 February 2019