India Jains: Why are these youngsters renouncing the world?

- Published

India's Jain community, a religious minority, has around 4.5 million believers

Hundreds of young people belonging to India's Jain community have begun renouncing the material world to become monks who always walk barefoot, eat only what they receive as alms and never bathe or use modern technology. The BBC's Priyanka Pathak explores why.

"I will never be able to hug my daughter again," says Indravadan Singhi, his voice breaking. He looks away, determined not to reveal emotion as he says, "I can never meet her eye again."

Resignedly, he watches friends and family drift through his home, decorating his living room with gold and pink tassels to celebrate his daughter's renunciation of the world and entry into monastic life.

In the days ahead of the ceremony, family came from around the country to spend her "last days" doing things she enjoyed - playing cricket in the local park, listening to music and eating out at her favourite restaurants. She will never be able to do these things again.

As a nun, 20-year-old Dhruvi will never again address him and his wife as mother and father. She will pluck out her own hair, always walk barefoot and eat only what she receives in alms. She will never use a vehicle, never bathe, never sleep under a fan and never speak on a mobile phone again.

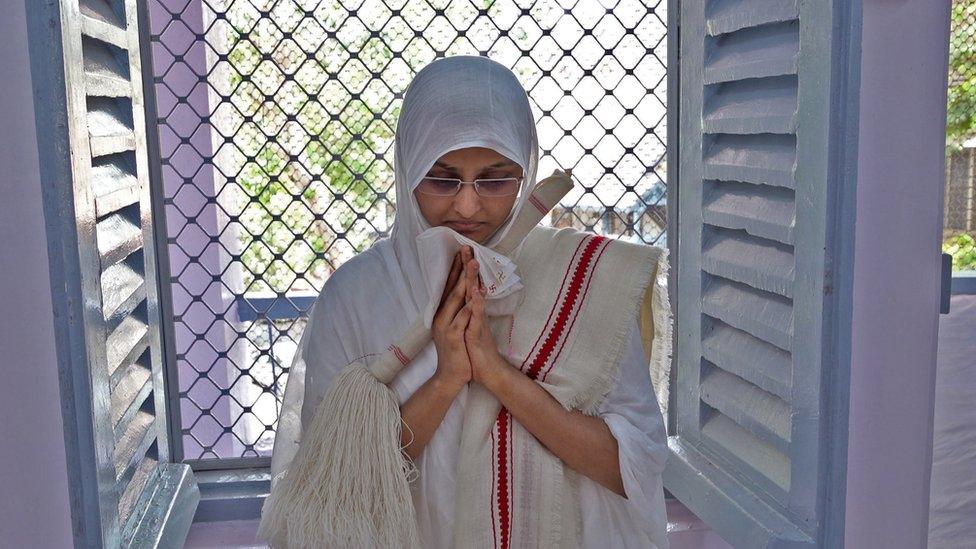

By undergoing deeksha, the Jain ritual of renunciation, Dhruvi (left) is withdrawing completely from the world

The Singhis belong to the ancient Jain community, a religious minority comprising around 4.5 million believers. Devout Jains follow the tenets of their religion under the spiritual guidance of monks. These include detailed prescriptions for daily life, especially what to eat, what not to eat and when to eat.

For the past five years, Indravadan Singhi and his wife have watched their only child - who loved ripped jeans and dreamed of winning the reality singing show Indian Idol - become increasingly religious and withdrawn.

By undergoing deeksha, the Jain ritual of renunciation. Dhruvi is withdrawing from the life she knows.

She is not alone. Hundreds of Jain youth are following the same path, their numbers rising each year, with women outnumbering the men.

"There used to be hardly 10-15 deekshas a year until a few years ago," says Dr Bipin Doshi, who teaches Jain philosophy at Mumbai University. But last year, that number rose to 250 and Dr Joshi says this year is likely to see close to 400 deekshas.

Community leaders attribute the rise to three things: growing disenchantment among the young with the pressures of a modern world, gurus of the faith adopting modern technology to make it easier for people to communicate religious ideas and finally, a superstructure of religious retreats that allows young people to experiment with monastic life long before they choose to commit to it.

Pressures of a modern life

The economic and social stresses of a "hyper-connected" world have contributed to this phenomenon, Dr Joshi says.

"What's happening in New York, or what's happening in Europe, you see it at the same moment. Earlier, our competition was restricted only to the streets in which we were staying. Now there is competition with all the world," he said, adding that Fomo - the Fear Of Missing Out - was driving more young people to try and escape everything.

"Once you take deeksha or renounce the world, your level of spirituality, social standing, religious standing becomes so high, even the richest man will come down and bow to you," he added.

Pooja Binakhiya, a physiotherapist who took deeksha last month, says the focus of her life changed completely after she became a nun.

Where her day was once filled with concerns like family, friends, beauty and career, she says she no longer has to think about how she will appear to her friends.

"Here we only think about soul, soul and soul," she says tranquilly.

The social-media gurus

Dhruvi, days ahead of her deeksha, says her guru is "everything to me".

"She is my world. Whatever she says, that is it."

Almost all Jain novices speak with similar warmth of their gurus. It is clear that these religious leaders also inspire tremendous obedience and loyalty.

Dr Doshi says that it was not always like this.

"Previously the ascetics were more introverted and interested only in their own self-purification," he says. But today, he adds, they are more involved and are actively reaching out to young people in particular.

"They are good orators and offer young people a path which is simple, they get attracted to it."

Until as recently as 10 years ago, Jains relied on literature written in the ancient Indian languages of Ardha Magadhi or Sanskrit. Now, the religious literature is offered in many languages, especially English.

"Stories of the Jain religion are made into short films, which are shareable on social media. Reading a book may not be important but just seeing one small story in a minute or two would influence youngsters a lot actually," Dr Doshi says.

These videos, which are mostly circulated via WhatsApp messages, are well produced films which often glorify renunciation and sometimes even portray monks as superheroes.

Muni Jinvatsalya Vijay Maharajsaheb, a Jain monk, says that over the last few years, films produced by Jain NGOs have played a critical role in making the religion accessible to young followers.

He himself has published several YouTube videos that have had over a million views. "If one wants to reach youngsters, it is easier to go to where they are rather than to try and bring them here," he says. "YouTube was the best choice because that is where young people spend most of their time online".

The religious retreats

Dhruvi says an Updhyan - a 48-day retreat she attended five years ago - was "the spark that made me consider a monk's life".

Under a presiding guru, the retreat allows regular Jains to experience a monastic life - without shoes, electricity and baths. Most novices point to this gruelling retreat - where gurus exhort them to renounce a world "full of sorrow" - as the moment they decided they want to be monks.

But such retreats cannot be undertaken overnight.

Hitesh Mota, who organises deekshas in Mumbai, say that most attendees undergo a series of short retreats to "slowly build the confidence that yes, I can live like this for a little bit longer next time".

"You know the fear of a monk's life, the fear of giving up everything. That fear is removed during the retreat. It is the first step, a sort of training camp to become a monk."

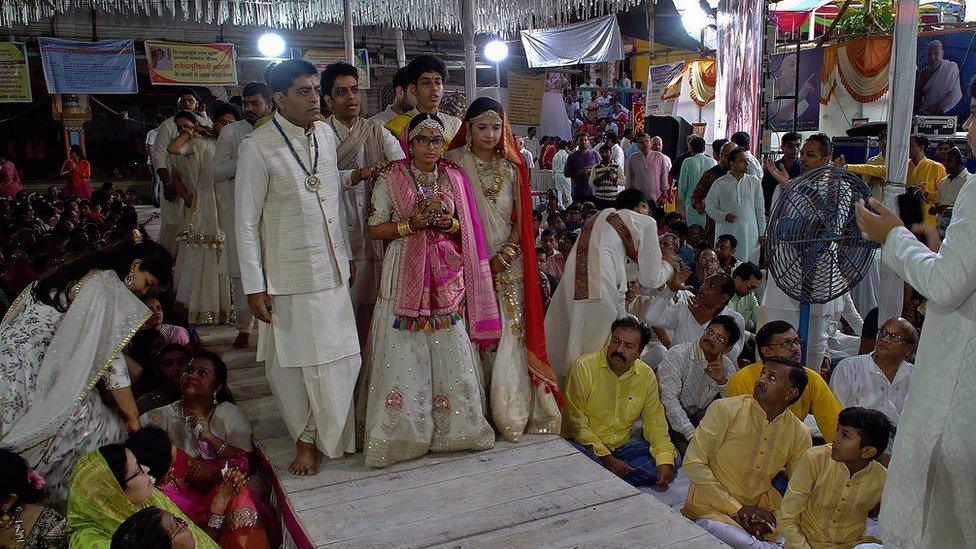

The number of young Jains choosing to renounce the material world is rising each year

Last month, a retreat in the western city of Nashik ended in a celebratory procession of chariots carrying 600 attendees wearing glittering clothes. Most were under 25 and reportedly hundreds of them expressed a desire to take deeksha.

Among them was 12-year-old Het Doshi.

A bright student and skating champion, Het missed three skating races and several weeks of school to attend this retreat. His feet were blistered and covered in boils and he lost 18kg (40lb) during the retreat, but Het says the flame had already been kindled in his heart.

"My guru has said there is nothing good in this world," Het said, uttering words he scarcely seemed to understand. "I don't like anything in this material world. I want to move away from my karmas, my sins. So I want to take deeksha. My guru says I should take it sooner rather than later, so I want to take it before I turn 15."

Although Het's parents want their child to become a monk, not all parents share this enthusiasm

His parents looked on proudly. But not everyone shares their children's enthusiasm for renunciation.

Dhruvi had to work very hard to get her parent's endorsement. "My family got very upset when I told them," she says.

She strategically stopped mentioning deeksha for a couple of years, aware that if she pushed too hard too quickly she could jeopardise her freedom to travel with her guru.

And even though she eventually wore down the family's resistance, their trepidation lingers just under the surface.

On the morning of Dhruvi's renunciation ceremony, her father hugged her for the last time before she donned the dress of a nun, grief etched on his face.

"All this pomp is one thing," he said. "Come back in two years to see how it has worked out."