Kashmir's crippled courts leave detainees in limbo

- Published

The families of two detained men have spoken to the BBC

Thousands of people have been detained in Indian-administered Kashmir following a government move to strip the region of its special status. Worried family members have been flocking to the courts - but to little avail, reports BBC Hindi's Vineet Khare.

Altaf Hussein Lone looked anxious as he sat on a red printed sofa in a large hall of the high court in Srinagar, the main city of Indian-administered Kashmir.

Since there is no public transport readily available, he had to pay an exorbitant amount to travel from his home in Baramulla, more than 50km (30 miles) away.

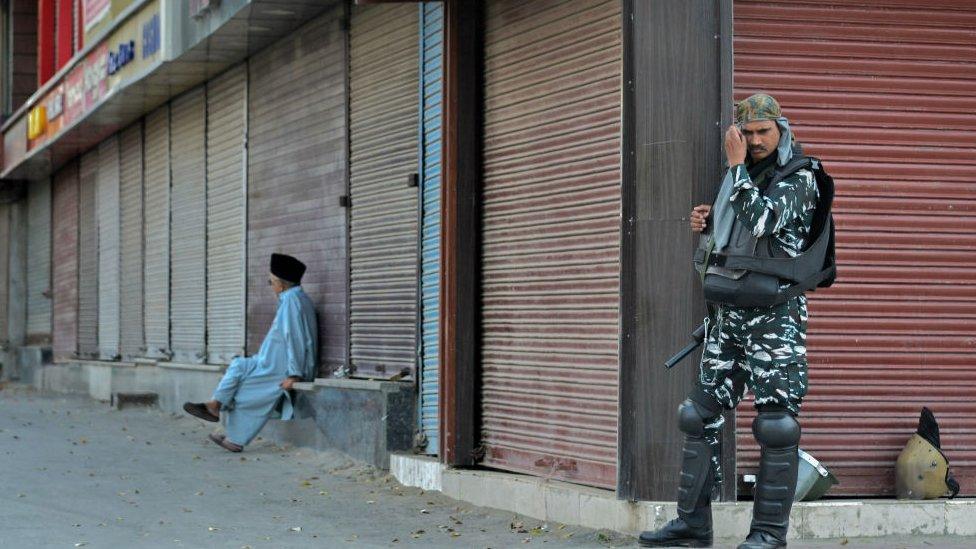

Life here has come to a standstill since the region lost its partial autonomy on 4 August. Internet and mobile phone connections remain suspended, roads and streets are largely deserted; and tens of thousands of extra troops have been deployed.

Despite government assurances that schools and offices can function normally, that has not happened. Most businesses have stayed shut as a form of protest against the government, but many owners also say they fear reprisals by militants opposed to Indian rule if they go back to business as usual.

Life in the region has come to a near standstill

Thousands of locals, including political leaders, businesspeople and activists, have been detained. Many have been moved to prisons outside the state.

Mr Lone was at the court looking for a lawyer to represent his brother, Shabbir, a village leader who had been arrested under the highly controversial Public Safety Act (PSA), external, which among other things, allows detention without formal charge for up to two years.

But he was unable to find one. Ironically, the lawyers of the Jammu and Kashmir Bar Association in Srinagar - a body representing more than 2,200 professionals - have been boycotting the courts for more than 50 days over the arrest of their present and former presidents, Mian Abdul Qauyoom and Nazeer Ahmed Ronga.

Both men were arrested under the PSA and sent to two different prisons in distant Uttar Pradesh state for "advocating secessionism" - a move that some lawyers describe as a "political vendetta".

The courts are conducting no business as the lawyers are on strike

This has left family members of detainees in the lurch.

Without a lawyer, Mr Lone is unsure of how to proceed - he has already submitted a habeas corpus petition to quash the charges against Shabbir.

Habeas Corpus, which translates from Latin to "you may have the body" is a writ that traditionally requires a person detained by authorities to be brought to a court of law so that the legality of the detention may be examined.

More than 250 petitions have been filed since 5 August, but none are being heard as the court has assigned only two judges to hear them, external. Apart from a lack of lawyers, the court is down to nine judges from the usual 17.

"I don't know what else to do," said a despondent Mr Lone, adding that he is now taking care of Shabbir's family - his wife and two young children - and their 80-year-old mother.

Lawyers say the strike will continue for as long as it takes to get their colleagues released.

While some lawyers are still helping people file habeas corpus petitions on behalf of family members, many don't appear in court. Petitioners or their relatives present themselves before the judge only to find out when they should appear in court next.

There has been a lot of anger against the Indian government decision

Tariq (name changed) who was also at the Srinagar court, said he was looking for a lawyer to represent his father-in-law who was arrested on 7 August. He said the 63-year-old was taken away by security forces close to midnight and spent several days at the local police station before being moved to Srinagar Central Jail.

"He followed the ideology of Jamaat-e-Islami [a militant group opposed to Indian rule in the region] but abandoned it five years ago," Tariq added. "We have been running around for a month now. He has had two surgeries."

The dismal state of affairs in the Srinagar high court was raised in the Supreme Court, and even prompted chief justice Ranjan Gogoi to announce that he would visit Srinagar, external to see for himself if the situation was as bad as reported. He has not announced a date to do so as yet.

But what it means is thousands of Kashmiris remain detained in prisons around the country.

"Normally, the court has to issue a notice within 48 hours of a Habeas Corpus petition being filed and the state has to respond before the case is listed on the fourth day. The case then has to be decided within 15 days. Now the process will take weeks, months and sometimes years," said Mudasir, a lawyer and a member of the Jammu and Kashmir Bar Association.

Thousands of Kashmiris have been detained and sent to jails across the country

Lawyers are also struggling to run their practices.

"We are not able to contact clients. During the initial days, there was a shortage of stamps and papers. We wrote bail applications on normal white paper," said Rafique Bazaz, a senior lawyer.

"People walked long distances to police stations for information and reports. We are short on stenographers to write petitions. No internet means we do not know the grounds of detention."

Despite the consequences however, Mr Bazaz said the strike would continue.

"This is a matter of rights and identity".

Read more on Kashmir:

- Published18 September 2019

- Published19 September 2019

- Published6 August 2019