Neelam Krishnamoorthy: The film tickets that destroyed a family

- Published

Neelam Krishnamoorthy's children loved watching films - but one afternoon a routine cinema trip ended in a moment of tragedy, and left Neelam fighting a decades-long battle for justice.

The moment

On the morning of 13 June 1997, Neelam Krishnamoorthy rang a popular cinema in Delhi - Uphaar - and bought two tickets for Border, a star-studded Bollywood film about the 1971 war between India and Pakistan.

It had hit the screens that day. It was the summer holidays and her children, Unnati, 17, and Ujjwal, 13, wanted to watch it.

"She [Unnati] was a big movie buff," says Neelam. "She wanted to see this movie first day. So I promised her I'd book the tickets for her."

Neelam remembers every moment of June 13 1997

The whole family ate lunch together - Neelam remembers the chicken curry her husband, Shekhar, had cooked. And she remembers the kiss Unnati planted on her cheek before she and Ujjwal left for the film. It was the last time she saw her children alive.

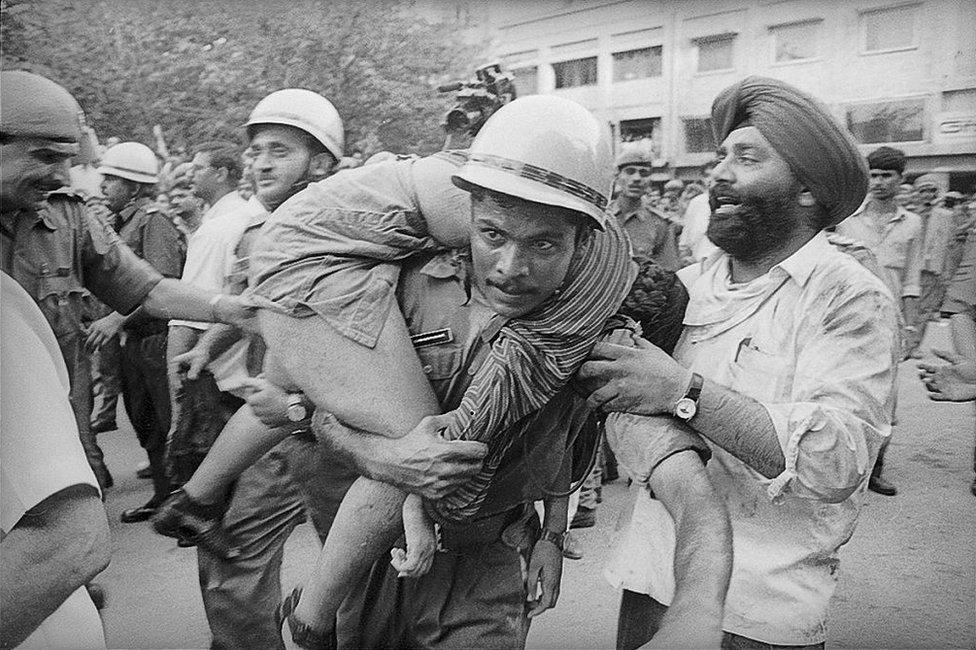

At 4.55pm, a fire broke out in the cinema's parking lot. The smoke spread up the stairs and entered the cinema hall. Witnesses said people poured out of the ground floor of the building, while some of those on higher floors smashed windows and jumped out to escape. But many were trapped inside as emergency vehicles laboured through evening traffic to reach the spot in the south Delhi neighbourhood of Green Park.

It was several hours before the Krishnamoorthys knew what had happened to their children. Neelam doesn't remember what time it was when she walked into a room full of stretchers in AIIMS hospital, and recognised Unnati's body. Ujjwal was on another stretcher, a few feet away.

"That's the day our world came to our end," she says. "Everything… just finished."

Fifty-nine people died, among them 23 children, the youngest one month old. More than a hundred were injured. It remains one of India's most tragic fires.

The fire at Uphaar cinema killed 59 people including 23 children

Soon, Neelam would learn that her children's deaths had been far from inevitable. And that discovery would drive her into a long, gruelling fight against powerful property developers, sluggish courts and, at times, her own unspeakable grief.

Before

The Krishnamoorthys' living room has birthday cards and photographs of Unnati and Ujjwal over the years - in one of them, she has her arm around him and they are both grinning.

Neelam picks up a thick photo album from the coffee table and starts turning the pages.

"This is on Ujjwal's 11th birthday..." she says wistfully, pointing at a photo of him cutting a cake. Neelam is also in the photograph - she's in bed with a fractured leg. Ujjwal insisted on cutting the cake in her bedroom, even though he had friends over.

Neelam says they were a close-knit, fun-loving family. They enjoyed eating out, they travelled a lot and they celebrated every birthday and anniversary. She describes her children as kind, outgoing and friendly.

In the summer of 1997, Unnati had finished school and was excited about college. Ujjwal was in the school choir, which he loved.

Unnati was 17 and Ujjwal, 13, when they died in the fire

The Krishnamoorthys have moved into a new home since then but Neelam has recreated the children's room like it was on that day. She doesn't allow outsiders into the room but she says she has kept every little thing that belonged to them - Ujjwal's cap is still on the bed where he left it.

She says she still goes into their room every morning and every night. "The time when I am very upset I go and sit in their room and I spend a lot of time there."

She has also held on to the most tangible reminder of that day: two pink, flimsy movie tickets.

She gingerly pulls them out of a black, leather wallet. It was a gift from her to Ujjwal.

The tickets are torn at the edges but you can see the timing of the show - Friday, 3.15pm - and the name of the cinema is printed across the middle.

"I call them tickets to death. As a mother I feel very guilty because I booked the tickets."

She also has Unnati's purse, which she was carrying that day.

The tickets, the wallet, the purse - they were all undamaged because Unnati and Ujjwal did not suffer any burns.

After

It was only days later that Neelam began to wonder what happened at Uphaar.

"I kept wondering why is it that only people in the balcony have died?"

Unnati, Ujjwal and all the other victims had been sitting in the balcony above the main hall.

Neelam and Shekhar have moved into a new house but they have recreated the children's room

"It was when I read the papers, I realised that the fire had started a long time back, the movie kept running, they were not informed, the doors were closed, the gatekeeper had run away. I mean, I realised they didn't have to die."

An inquiry into the fire found that this had indeed been the case.

The owners had added 52 extra seats in the balcony over the years, blocking a crucial exit and narrowing paths to the other exits.

There were also no emergency lights or footlights. Survivors from the balcony told the court that they stumbled towards the exits in pitch darkness. Some managed to pry open a locked door and squeeze through only to faint in the smoke-filled lobby. But those inside choked to death on carbon monoxide fumes.

This is the crux of Neelam's 22-year-long fight: the deaths were a man-made disaster, the result of broken rules and lax enforcement.

The inquiry also found that the transformer in the basement that had caused the fire had not been installed correctly, increasing the risk of fire. It had caused another fire earlier that day, which had been quickly put out, but shoddy repairs resulted in the second and fatal fire.

All those who died were sitting in the balcony above the main hall

The more Neelam learnt, the angrier she got. And the more convinced she became that she had to fight for her children.

"I told Shekhar I want to get the people responsible for this tragedy. I want to send them behind bars."

India has a dismal record in public safety and tragedies like these are alarmingly common. But what is rare is for victims' families to hold someone accountable. So Neelam and Shekhar's decision to do that unnerved family and friends. Some suggested that they have another child to move on - but this was never an option for the couple.

"You do everything for your children [while] they are alive," says Neelam. "So why would I stop doing something for them when they are no more?"

This is the second in a series of stories on moments that drastically altered Indian lives

You can listen to Neelam Krishnamoorthy's story on Outlook, on the BBC World Service - click here for transmission times, or to catch up online

Read the first of the series here - The fake spy scandal that blew up a rocket scientist's career

This series is produced by the BBC's Geeta Pandey in Delhi

The state accused 16 men of causing the deaths in Uphaar - they included staff at the cinema, and safety inspectors who overlooked glaring violations throughout the building. The most high-profile accused were Sushil and Gopal Ansal, two brothers who owned the cinema.

Neelam and Shekhar formed an association with families of the other victims to support the prosecution. And Neelam started to educate herself about everything, from safety rules for cinema halls to criminal law. But nothing prepared her for India's overburdened and understaffed courts.

It was a decade later - in 2007 - that the court finally found all 16 men guilty, by which time four of them had died. The sentences ranged from seven months to seven years - some were found guilty of negligence, while others were found guilty of more serious charges. The Ansal brothers were given two years in jail, the maximum sentence for their charge.

"It came as a shock to me that they gave just a two-year sentence for someone responsible for killing 59 lives," says Neelam.

Neelam says her children are what give her the strength to keep going

She had been fighting for them to be charged with a graver offence, on the grounds that decisions they took, as the cinema's owners, had proved fatal.

But when she challenged the sentence in the Delhi high court, rather than being increased, it was halved.

"The reason given was that they are educated, they have a good social status," says Neelam. "I found those reasons pretty pathetic. Because if you are educated, you should have been more prudent and followed all the rules."

So she appealed to the Supreme Court, which delivered its ruling in 2015. And this time the Ansal brothers' custodial sentences were waived altogether. Instead, each was fined $4m.

"I just threw all the documents I had in the court," she says, recalling that day. "I walked out of the court and I burst into tears. That was the first time I cried publicly."

She says that day, she and Shekhar couldn't visit the children's room - they spent the whole night in the drawing room, wondering what they could have done differently.

It was a ruling, she says, that shook her faith in the judiciary. But she eventually went back to the Supreme Court for another appeal. This time, the court ordered Gopal Ansal to serve one year in jail. Sushil Ansal, then 77, was released on account of old age.

The Krishnamoorthys are still doing the rounds of courts

That was in 2017. Neelam has one more challenge pending. She has petitioned the Supreme Court again, asking for the Ansals to serve the full two years of their original sentence, since neither of them has completed two years in jail. She doesn't know when the court will begin its hearings.

Over the years, she has committed the case to memory - every order, appeal, verdict and document that is spilling out of the boxes and shelves in her home office.

"I have read every single document," she says. "There are almost 50,000 pages to be read in the main case alone."

She says she has lost count of how many hearings Shekhar and she have attended - they still spend hours in courtrooms every other day. And she takes copious notes so she is always in the loop, and can question or prod the prosecutor if necessary.

What keeps them going, Neelam says, is the promise they made to their children to get justice for them - although at times, she feels like she has failed them and despair takes over.

"If I had to do it all over again, I would just pick up a gun and shoot the guys who were responsible for my children's death. I would not like to go through this trauma. After killing them, I can kill myself so I don't suffer. As simple as that."

The memorial is in a park opposite Uphaar cinema

Uphaar cinema is still standing - grimy and dilapidated, it bears the marks of the tragedy 22 years ago. It can't be torn down until judges have ruled on Neelam's final challenge.

"I try not to even look at this building when I come here," says Neelam, standing with her back to it. "I had my bank right here. I didn't visit it for almost 12 years."

Across from Uphaar is a small park with a round black granite fountain - a memorial to the victims of the fire. It has their names with their date of birth.

Neelam visits the park three times a year - on her children's birthdays and on the anniversary of the fire. She goes straight to the memorial, touches the spot where Unnati's and Ujjwal's names are inscribed, folds her hands and closes her eyes.

"I just pray because I think... this is where they died and I very strongly feel that they are still not at peace."

You may also be interested in:

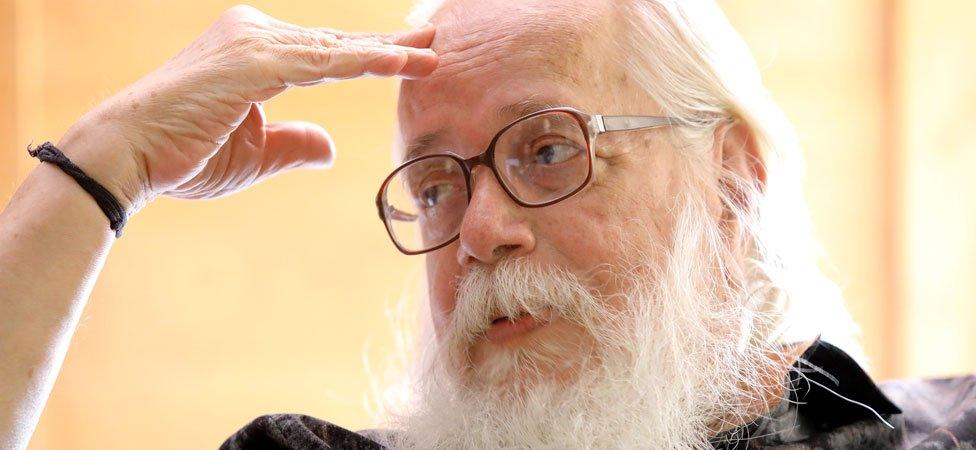

Imagine your life being changed by a single dramatic moment. This is what happened to a top scientist in the Indian space programme, when one day, 25 years ago, police officers knocked at his door.

The fake spy scandal that blew up a rocket scientist's career