Delhi Nirbhaya rape death penalty: What do hangings mean for India's women?

- Published

Four men found guilty of the gang-rape and murder of a 23-year-old woman on a bus in the Indian capital, Delhi, seven years ago have been hanged.

The hangings were the last step in the brutal December 2012 rape case that stunned India, brought thousands of protesters out on the streets and made global headlines for weeks.

It also forced the authorities to bring in more stringent laws, including the introduction of the death penalty in rare cases.

The judges perceived this particular crime fit for awarding the death penalty and on 20 March, the convicts were executed.

Delhi Nirbhaya rape death penalty: How the case galvanised India

Despite the outcry over the crime and the government's promise to deliver quick justice, the case had meandered through courts for more than seven years.

The hangings have been welcomed by the victim's family. Her mother, Asha Devi, who had become the face of the campaign to carry out the death sentences, has said that justice has finally been done.

There have been celebrations outside the prison where the executions took place with many chanting "death to rapists".

But will it make women any safer in India?

A short answer to that question would be: No.

And that's because despite the increased scrutiny of crimes against women since December 2012, similar violent incidents have continued to make headlines in India.

According to government data, thousands of rapes take place every year and the numbers have been consistently rising over the years.

Recently-released figures from the National Crime Records Bureau show police registered 33,977 cases of rape in 2018 - that's an average of 93 every day.

And statistics tell only a part of the story - campaigners say thousands of rapes and cases of sexual assault are not even reported to the police.

I personally know women who have never reported being assaulted because they are ashamed, or because of the stigma associated with sexual crimes, or because they are afraid that they will not be believed.

Even so, the daily newspapers are full of horrific reports of violations and it seems no-one is safe - a victim could be an eight-month-old or a septuagenarian, external, she could be rich or poor or middle class, an assault could take place in a village or the big city, inside her own home or on the street.

The rapists do not belong to a particular religion or caste, they come from different social and financial backgrounds.

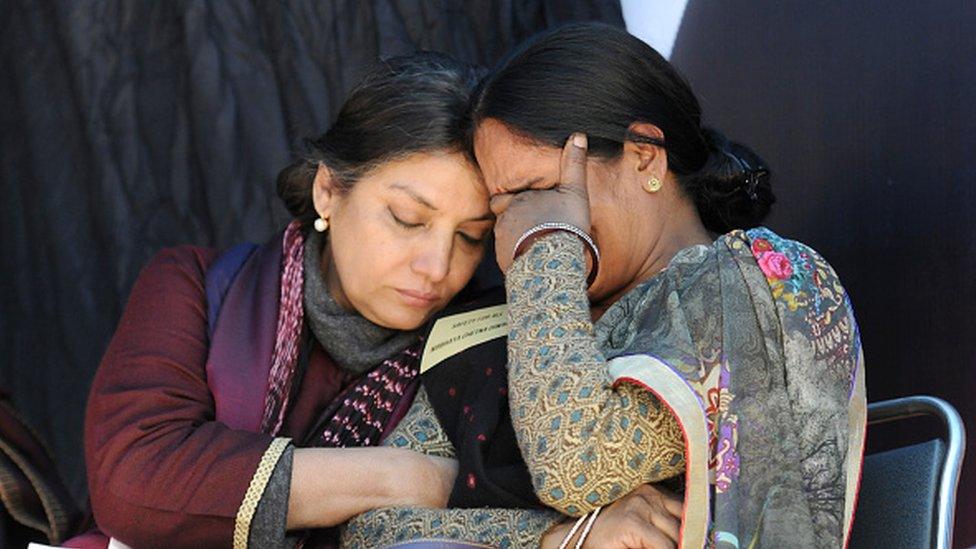

The Delhi bus rape victim's mother Asha Devi had become the face of the campaign to carry out the death sentence

And they are everywhere - lurking in homes, playgrounds, schools and the streets - waiting for an opportunity to strike.

In November, a 27-year-old vet was gang-raped and murdered in the southern city of Hyderabad. Later, her body was set on fire.

A few days later, in Unnao district in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh, a woman was set on fire while she was on her way to testify against her alleged rapists. She sustained 90% burns and died in hospital three days later.

Another woman, also in Unnao, was seriously injured in a car crash in July after she accused a ruling party lawmaker of rape. Two of her aunts were killed in the crash, and her lawyer was seriously injured.

She alleged that the police had ignored her complaints for months preceding that. In fact, she alleged they had colluded with the alleged rapist and arrested her father who then died in custody.

The legislator was arrested only after she threatened to kill herself, and the national press began reporting on her allegations. In December, a court pronounced him guilty and sentenced him to life in jail.

All these cases, the brutality of the abuse, the entitlement displayed by men in power, do not give women much confidence.

Some say strict punishment, swiftly delivered, will instil a fear of the law in the public mind and deter rape, but experts say the only permanent solution to the problem is to dismantle the hold of patriarchal thinking, the mindset that regards women as being a man's property.

They say the family and wider society need to recognise their role in making India a safer place for women; that parents, teachers and elders must deal with every transgression, however minor, and not indulge bad behaviour with "boys-will-be-boys" remarks.

Last year, the government said they had started gender sensitisation programmes in schools to teach boys to learn to respect women. The idea, they said, was to catch them young, in their formative years, to make them better men.

This could definitely help, but one of the major problems with such ideas is their patchy implementation and the long time they take to show results.

Until that happens, how do women and girls in India ensure their safety?

By doing what we always do - that is, by restricting our own freedoms.

The Delhi gang-rape victim couldn't be named under Indian law so the press dubbed her Nirbhaya - the fearless one. But as most women will tell you, that's not how we really feel.

We dress modestly while going out, we don't stay out late, we keep looking over our shoulders at all times, we drive with our doors locked and windows rolled up.

And sometimes, safety comes at a cost too.

Like when two years back I had a flat tyre while driving home at night, I didn't stop until I reached my regular petrol station where I knew the mechanics.

By then, my tyre had been shredded to pieces. Next day, I had to pay for a new tyre, but I think I got away cheaply.

Read more from Geeta Pandey

- Published6 December 2019

- Published13 December 2019

- Published16 December 2017