Why India is greeting Amazon's Jeff Bezos with protests

- Published

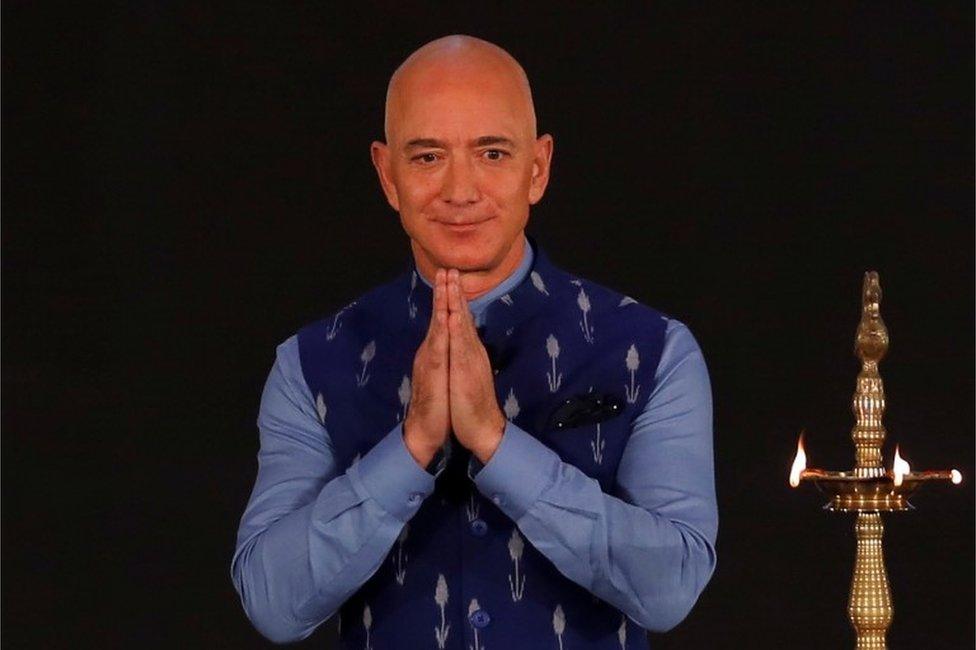

Jeff Bezos is visiting India for the third time

The last time Amazon boss Jeff Bezos was here, he wore a long Indian coat, climbed into a gaudily decorated truck, posed for pictures and promised to invest a couple of billion dollars. He also gave dozens of media interviews. "You hear all the time that there are so many obstacles in doing business in India, but that's not our experience," he told a newspaper.

Five years on, the world's richest man has arrived on a two-day visit to a much less enthusiastic reception.

A union of small traders who claim to represent tens of millions of brick-and-mortar businesses have planned protests in 300 cities against Mr Bezos, accusing his firm of predatory pricing. They complain that the online giant's now six-year-old retail operation in the country is hurting them badly. Praveen Khandelwal of the Confederation of All India Traders, which is organising the protests, says Amazon's "sinister game and evil designs" have "already destroyed the business of tens of thousands of small traders" in India.

If this was not enough, hours before Mr Bezos's arrival, India's anti-trust regulator opened a formal investigation into the business practices of Amazon and its Indian competitor Flipkart, an Indian e-retailer, mostly owned by Walmart.

The regulator says it is looking into allegations of predatory pricing, the exclusive launch of mobile phones, deep discounting and preferential treatment of selected sellers by the online giants, among other things. Amazon said in a statement it would co-operate, address the allegations and was "confident in our compliance [with local rules]".

Traders says Amazon is hurting small businesses

Amazon claims to have done a lot to empower retailers in India, its fastest-growing market.

With more than 60,000 employees and $5bn of investment in the country, the Seattle-based giant says it works with more than half a million sellers on the market place. (Under Indian laws, the site can only sell third-party goods from independent sellers.) More than half of the sellers come from small towns and cities, and many have grown rich during the site's popular festival sales, the firm claims.

Amazon also partners with small, so-called mom-and-pop stores to help customers buy products from the site for a commission. Some 50,000 Indian sellers have shipped $1bn worth of goods to destinations outside India, under a programme that enables them to list and sell their products around the world, the company claims.

On Tuesday, Mr Bezos announced that Amazon would aim to export goods worth $10bn from India by 2025. He also promised to invest $1bn in digitising small and medium businesses here. Mr Bezos is attending a company event in Delhi to fete small and medium businesses who partner with his firm. These initiatives do not appear to impress the protesters. "Mr Bezos is creating a false narrative of empowering small retailers," Mr Khandelwal says.

Mr Bezos attended a company event in Delhi

Amazon and Flipkart overwhelmingly dominate India's $39bn online retail market. Fuelled by an explosion of mobile phone subscribers - more than a billion already - and cheap data, it is the fastest growing e-commerce market and is expected to grow to $120bn in 2020. E-commerce attracted 124 rounds of international investor funding in 2017 alone. There are now more than 4,700 such start-ups in India.

But India is also a country where neighbourhood stores thrive.

These nifty stores - called kirana or neighbourhood corner shops - continue to rule the brick-and-mortar retail space. According to consulting firm PricewaterhouseCoopers, there are 12 million such stores in India and an increasing number of them are adopting technology - accepting debit and credit cards and wallet payments, for example - to serve customers better. Researchers at the Indian School of Business who analysed more than a million sales transactions of a fast-moving consumer goods company in India with corner shops and organised retail for three years found that the mom-and-pop stores had a higher ability to earn a profit than modern trade outlets.

Amazon says its sellers have grown rich through festival sales

Amazon is no stranger to battling regulators around the world. Last year EU anti-trust regulators opened an investigation after allegations that Amazon misuses "sensitive data" from independent retailers who sell on the online giant's website. The retailers' relationships with sellers of third-party goods is also being investigated in the US and Europe.

India is a promising, but tricky market. On the one hand, India's small traders are often seen as resistant to change and protectionist in nature. They also receive the backing of populist political parties.

On the other hand, there are genuine fears about the future of small brick-and-mortar businesses which face the onslaught of online giants. Consumers are largely happy with the speedy delivery and low prices that the e-commerce giants offer. And the government needs foreign investment to grow a slowing economy. How the regulator and Mr Bezos negotiate the maze will be interesting to see.

- Published15 January 2020