Why Delhi violence has echoes of the Gujarat riots

- Published

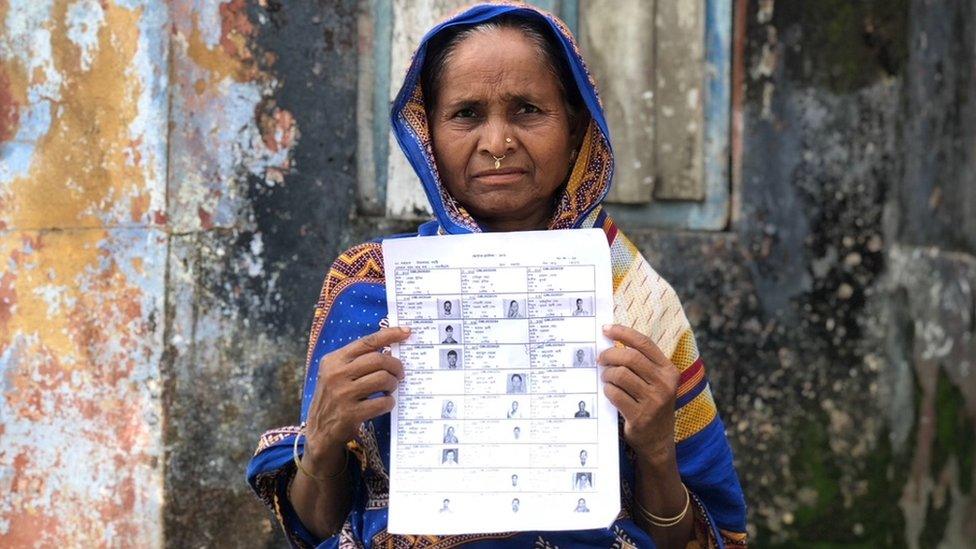

Delhi remains on edge after three days of rioting

The religious violence which has roiled Delhi since the weekend is the deadliest in decades.

What began as small clashes between supporters and opponents of a controversial citizenship law quickly escalated into full-blown religious riots between Hindus and Muslims, in congested working class neighbourhoods on the fringes of the sprawling capital.

Armed Hindu mobs rioted with impunity as the police appeared to look the other way. Mosques and homes and shops of Muslims were attacked, sometimes allegedly with the police in tow. Journalists covering the violence were stopped by the Hindu rioters and asked about their religion. Videos and pictures emerged of the mob forcing wounded Muslim men to recite the national anthem, and mercilessly beating up a young Muslim man. Panicky Muslims began leaving mixed neighbourhoods.

On the other side, Muslim rioters have also been violent - some of them also armed - and a number of Hindus, including security personnel, are among the dead and injured.

Delhi religious riots: 'Mobs set fire to my house and shop'

Three days and 20 deaths later, Prime Minister Narendra Modi tweeted his first appeal for peace. There were no commiserations for the victims. Delhi's governing Aam Aadmi Party was criticised for not doing much either. Many pointed to the egregious failure of Delhi's police - the most well-resourced in India - and the inability of opposition parties to rally together, hit the streets and calm tensions. In the end, the rioters operated with impunity, and the victims were left to their fate.

More than 20 people have been killed in the rioting

Not surprisingly, the ethnic violence in Delhi has drawn comparisons with two of India's worst sectarian riots in living memory. Nearly 3,000 people were killed in anti-Sikh riots in the capital in 1984 after the then prime minister Indira Gandhi was assassinated by her Sikh bodyguards. And in 2002, more than 1,000 people, mostly Muslims, died after a train fire killed 60 Hindu pilgrims in Gujarat - Mr Modi was then the chief minister of the state. The police were accused of complicity in both riots. The Delhi High Court, which is hearing petitions about the current violence, has said it cannot let "another 1984" happen on its "watch".

Ashutosh Varshney, a professor of political science at Brown University who has extensively researched religious violence in India, believes that the Delhi riots are beginning to "look like a pogrom" - much like the ones in 1984 and 2002.

Pogroms happen, according to Prof Varshney, when the police do not act neutrally to stop riots, look on when mobs go on the rampage and sometimes "explicitly" help the perpetrators. Evidence of police apathy in Delhi has surfaced over the past three days. "Of course, the violence thus far has not reached the scale of Gujarat or Delhi. Our energies should now focus on preventing further escalation," he says.

Political scientist Bhanu Joshi and a team of researchers visited constituencies in Delhi ahead of February's state elections. They found the BJP's "perfectly oiled party machinery constantly giving out the message about suspicion, stereotypes and paranoia". In one neighbourhood, they found a party councillor telling people: "You and your kids have stable jobs, money. So stop thinking of free, free. [She was alluding to free water and electricity being given to people by the incumbent government.] If this nation doesn't remain, all the free will also vanish." Such paranoia about the security of the nation at a time when India has been at its most secure has "widened" existing ethnic divisions and "made people suspicious", Mr Joshi said.

Mosques have been vandalised in the clashes

In the run-up to the Delhi elections Mr Modi's party embarked on a polarising campaign around a controversial new citizenship law, the stripping of Kashmir's autonomy and building a grand new Hindu temple on a disputed holy site. Party leaders freely indulged in hate speech, and were censured by poll authorities. A widely reported protest against the citizenship law by women in Shaheen Bagh, a Muslim-dominated neighbourhood in Delhi, was especially targeted by the BJP's campaign, which sought to show the protesters as "traitors".

"The repercussion of this campaign machine is the normalisation of suspicion and hate reflected in WhatsApp groups, Facebook pages, and conversations families have among themselves," says Mr Joshi.

It was only a matter of time before Delhi's fragile stability would be shaken. On Sunday a BJP leader issued a threat, telling the Delhi police they had three days to clear the sites where people had been protesting against the citizenship law and warned of consequences if they failed to do so. The first reports of clashes emerged later that day. The ethnic violence that followed was a tragedy foretold.

- Published30 July 2018

- Published30 July 2018