Coronavirus: Herbal remedies in India and other claims fact-checked

- Published

False and misleading information has been spreading on Indian news channels and social media posts as the authorities attempt to control coronavirus with strict restrictions on movement throughout the country.

We've been looking at some of the most prominent examples.

Traditional herbs won't boost your immunity to the virus

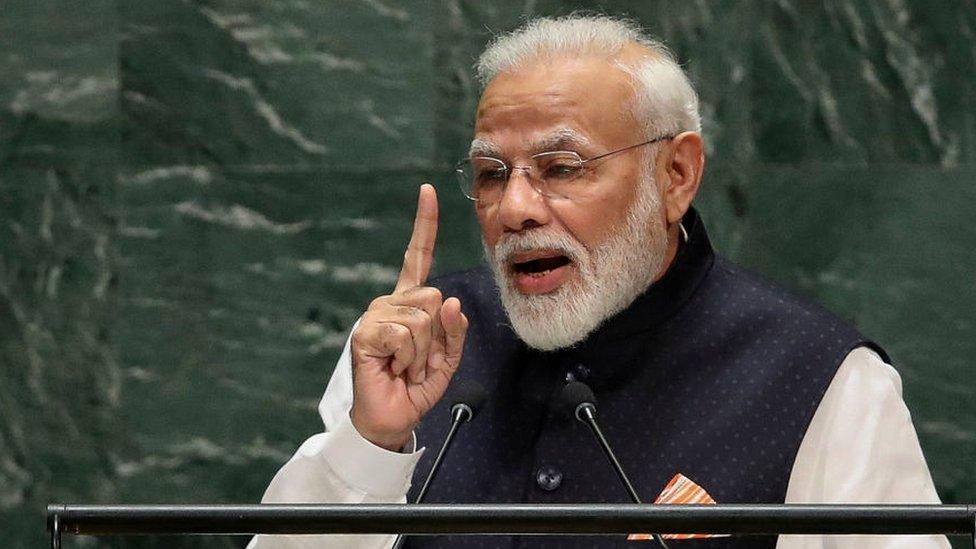

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi's strategy against the coronavirus includes advising citizens to use traditional herbs.

Mr Modi has announced a seven-point plan to combat the virus

Mr Modi has said people should follow official guidance to use a particular herbal combination, external known as "kadha" which will "increase immunity."

The immune response is what the body does when it fights off a virus but there is no evidence that it can be boosted in this way, say medical experts.

"The problem is that many of these claims (about certain supplements boosting immunity) have no grounding in evidence," says Akiko Iwasaki, an immunologist at Yale University.

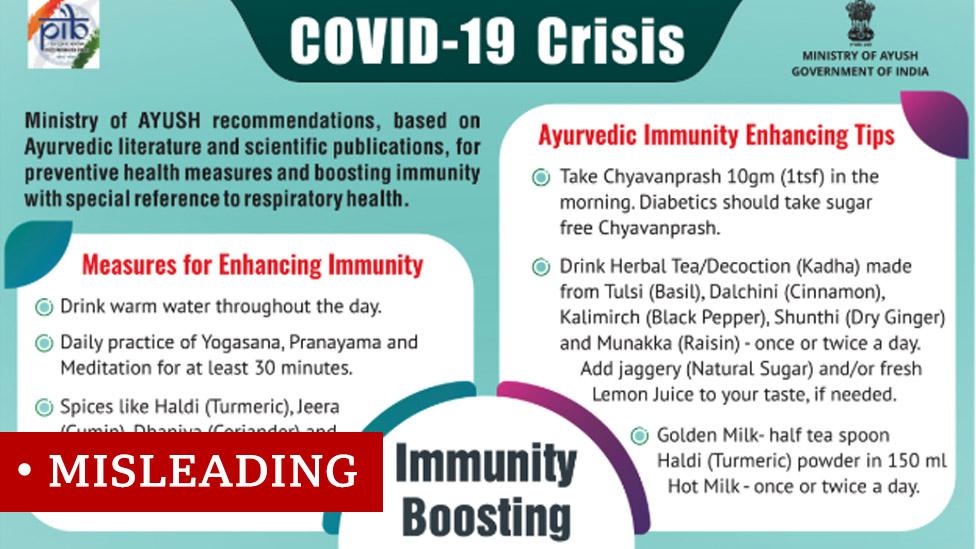

India's Ministry of Ayurveda, Yoga & Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha and Homoeopathy (AYUSH) promotes traditional healing therapies and lists various practices for boosting the immune system.

Many of these remedies have been promoted by the ministry to specifically ward off the coronavirus.

There is however no scientific evidence that they are effective.

The Indian government's own fact-checking service has already debunked similar health claims, such as around drinking warm water - or gargling with vinegar or salt solutions, external.

Below, we take a look at one these traditional remedies, the drinking of tea, and how a fake claim originating in China, has been picked up and spread elsewhere, including India.

A non-existent study on the impact of the virus

A popular Hindi TV channel, ABP News, reported there was research to show that if there hadn't been a nationwide lockdown, there would have been 0.8 million people in India infected with coronavirus by 15 April.

The TV channel attributed this figure to a top medical research organisation - the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR).

The ruling Bharatiya Janata Party's (BJP) information technology chief, Amit Malviya, tweeted out this story, external, getting thousand of views and retweets.

But the Indian Health Ministry says there's no such study, something which was confirmed by the ICMR itself.

"The ICMR has never carried out any study saying that a lockdown would have had such an impact," Dr Rajnikanth, regional head of research management and policy, told the BBC.

ABP News has stood by its story, despite the Health Ministry denying it.

However, the ministry has acknowledged there had been some "internal research" about predicted infection numbers which has not been made public.

The actual number of infections that there would have been without a lockdown can't be known, of course, as people in India have been under strict restrictions of movement since 25 March.

A fabricated post about tea drinking

"Who would have known that a simple cup of tea would be the solution to this virus."

This false claim - shared on social media - refers to the Chinese doctor Li Wenliang, who was hailed a hero for his efforts to raise the alarm about the virus early on in Wuhan, and who later died of the disease.

It claims that in his case files, the doctor had documented evidence that substances commonly found in tea - known as methylxanthines - can decrease the impact of the virus.

The widely shared post also falsely claimed that hospitals in China were giving Covid-19 patients tea three times a day.

It's true that methylxanthines are found in tea, as well as in coffee and chocolate.

But there's no evidence Dr Li Wenliang was researching their effect - he was an eye specialist, rather than an expert on viruses - nor that hospitals in China were treating Covid-19 by giving patients tea.

LATEST: Live coverage of developments

EASY STEPS: What can I do?

A SIMPLE GUIDE: What are the symptoms?

MAPS AND CHARTS: Visual guide to the outbreak

VIDEO: The 20-second hand wash