India coronavirus: Gambling on lockdown to save millions

- Published

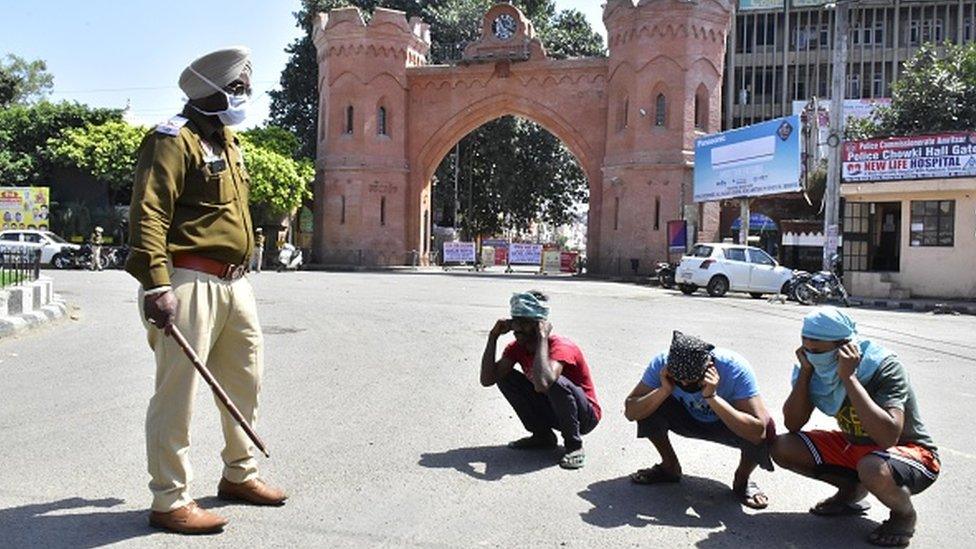

The brutal lockdown will extract a huge economic cost

India is on pause. The streets are empty, the skies vacant, railways silent. Nearly everything is shut. People have been asked to stay at home. Time stands still.

But the eerie stillness of a 21-day lockdown of the world's second most populous country to prevent the spread of coronavirus is a deceptive exterior to the chaos brewing within.

As India ended the second day of this unprecedented hiatus from life and work, reports and videos turned up showing how potentially disruptive this move could be in a chaotic, under-resourced democracy.

It's early days yet, and things may improve. But how India copes with the economic and social fallout of its biggest ever disruption, possibly since the bloody partition at the end of British rule in 1947, will be watched keenly. It will also be the biggest test for any government since the founding of the republic.

Scenes in India as 1.3 billion people are ordered to stay indoors

The severe restrictions India has imposed on its people to stop runaway community transmission of a lethal virus will inevitably extract a huge economic cost. But the reality is that the country simply had no choice. It has been testing low, and below its capacity, for some weeks now, and it still doesn't have a handle on the extent of the spread of the infection. (India has recorded 649 cases, and 13 deaths so far.) Data is scarce.

Migrant workers, out-of-work and without wages, are walking back to their villages - many of which are hundreds of miles away - because there's no transport. The poor and the homeless are flocking to makeshift gruel kitchens. Panicky policemen are using force to seal state borders and keep the streets empty.

Essential supply trucks are stuck and home deliveries stalled, resulting in shortages and inflation. Chinks are already showing in the government's messaging and planning: a senior bureaucrat has tweeted saying he will try to act on complaints that e-commerce giants like Amazon have suspended services because their employees are not able to come to work.

Thousands of workers are stranded

The government also knows that if the infection spreads unhindered in India's heaving cities, there will be mass death. By keeping people at home, India has one chance to avoid or mitigate a looming catastrophe. If the country had waited longer and the disease spread, it could have led to its people and economy being decimated. "To be honest, there was no other option. We had to shut down," Pratap Bhanu Mehta, a prominent public intellectual, told me.

India, say many, is now in a "war-like" situation. On the one hand, the battle against a stubborn virus has just begun. On the other, as economist Rathin Roy says, the government has to move quickly to a crisis mode "similar to fiscal response in war time". There's no time to lose.

On Thursday, the government announced a $22bn (£19bn) bailout for the country's poor. This will pay for cash, transfers and free food to the needy, and health insurance for health workers, among other things.

Policemen are using force to seal state borders and keep the streets empty

India's array of public welfare schemes has helped build up an impressive database of hundreds of millions of recipients. That needs to be mined to quickly transfer cash into the bank accounts of the needy - farmers, daily wagers and informal workers who comprise the bulk of the labour force. Those who are unbanked have to be given cash and food and access to supplies of essentials.

Sticking to the protocols of social distancing, supply chains have to ease quickly. Farmers and manufacturers need to be clear about whether a truck can come and take their produce and goods to the markets. The police, enforcing the lockdown with characteristically coercive enthusiasm, have to be told what can and cannot be stopped. Millions of informal and gig economy workers have to be paid to stay at home.

The streets are empty, the skies vacant, railways silent

Half a dozen states have already moved in this direction. They have announced direct cash transfers to millions of workers, advanced pensions for the old and disabled, made available free food and medicine, and dry rations for school children at home. Self-help groups are being roped in to give out consumer loans in the southern state of Kerala. Utility bill payments are being deferred and eateries being opened for cheap meals. The oil price crash - India is a major importer - will give the country some extra cash.

Yet, all this might still not be sufficient to tide over this "war-like" challenge.

How long, for example, will it take for supply lines to begin moving smoothly so that people can buy their food and essentials?

Despite the government's assurances, thousands of trucks carrying food and cooking gas, among other goods and commodities, are reportedly stuck at sealed-off state borders. The drivers have no food or water. "The police are not even willing to talk to us," a trucker told a journalist.

State borders are shut

Whether the promised assistance to the poor and vulnerable reaches them in time is also a major concern: many of the more populous northern states like Uttar Pradesh and Bihar have a poor record of delivery. "People are right to express concerns about the livelihood and economy. Your best hope is to inflict some pain now, contain the spread of the disease now or face disaster later," says Prof Mehta.

Yet, India, with its chronically underfunded and leaky state, can surprise sceptics. A state that largely fails to deliver quality public health and education to its people excels in "mission mode" with deadline-driven, specific targets.

It went door-to-door, and vaccinated more than 170 million children and eradicated polio. It regularly holds trouble-free votes involving hundreds of millions of people - 67% of the 910 million eligible voters cast their ballots in the 2019 general election. An under-developed and crime-ridden state like Uttar Pradesh, with a population of the size of Brazil, regularly hosts the Kumbh Mela, the world's biggest open air religious gathering of people. It prepared for more then 100 million pilgrims last year, without a single stampede or health scare. It is all very counter-intuitive.

Has India shut down early, or late, or just in time?

"The Indian state," says Prof Mehta, "is not very good at routine stuff, but very good in mission mode." It also helps that Indians, especially faced with a crisis, show unusually high levels of social cohesion and adaptability.

Over the years an increasing number of states have beefed up capacity for delivering welfare schemes and services more efficiently. Kerala has been a shining example for years. But now, even states like Orissa in the east are catching up: it has given 500,000 rupees ($6,626; £5,582) to every village council to build a quarantine centre, in what is seen as exemplary strategic disaster planning.

India's mission-mode capacities will be now put to the test in more ways than one.

India, with its chronically underfunded and leaky state, can surprise sceptics

Experts say that it should use this time to ramp up testing, swiftly identify clusters of infection, and move resources - beds, ventilators and doctors - to those areas. India will need to hunt down its hidden positive patients, isolate and treat them.

Most importantly, India has to decide what to do after the 21 days are over. It is not clear if the government has enough data to decide as yet. So is it going to be a trade-off between easing the lockdown and seeing if more people get infected and then shutting down things again? Farzad Mostashari, former national co-ordinator for Health Information Technology and the US Department of Health and Human Services, says the "confluence of politics, policy and data" will decide "when we go in for extreme measures and when we come out of it". Has India shut down early, or late, or just in time? Time will tell.

"The India lockdown is the biggest in history," Howard Markel, who studies the history of pandemics and is director of the Center for the History of Medicine at the University of Michigan, told me.

"I hope it works - but it needs to be implemented early and for a long time. Stay the course - and we'll save our lives together."

- Published24 March 2020

- Published20 March 2020