Coronavirus in India: Desperate migrant workers trapped in lockdown

- Published

Manoj Ahirwal right and his mother Kalibai (centre) are desperate to return home

Last week, hours after Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi extended a nationwide lockdown to contain the spread of the coronavirus, thousands of migrant workers gathered near a railway station in Mumbai city.

There had been rumours of train services restarting, and the workers had gathered defying rules of social distancing, putting themselves and others at risk.

They demanded that authorities arrange transport to send them back to their hometowns and villages so they could be with their families. The police, instead, used sticks to disperse them.

Around the same time, in the western state of Gujarat, hundreds of textile workers protested in Surat city, demanding passage home.

And a day later, there was outrage in the capital, Delhi, when several hundred migrants were discovered living under a bridge along the Yamuna river. The river here resembles a sewer and the bank is strewn with rubbish.

Mumbai: Frantic migrants throng Bandra station as India extends lockdown

The men were unwashed and said they had not eaten in three days, since the government shelter they lived in was burned down. They have now been moved to new shelters.

The incidents have shone a spotlight the plight of millions of poor Indians who migrate from villages to cities in search of livelihood - and how the lockdown has left them stranded far away from home, with no jobs or money.

The problem of migrant workers may not be entirely unique to India, but the sheer scale - there are more than 40 million migrant labourers across the country - makes it difficult to provide relief to everyone.

Most move from villages to work in the cities as domestic helpers, drivers and gardeners, or as daily-wagers on construction sites, building malls, flyovers and homes, or as street vendors.

One critic said the mismanagement of the migrant crisis and the treatment of its poorest citizens during the pandemic could be India's shame.

Textile workers protested in Surat city, demanding a passage to their homes in other parts of India

Whether living in shelters, sleeping on footpaths or under flyovers, the migrants are restless and are waiting for restrictions to be eased so they can go home.

A few days back, I visited one shelter in east Delhi, located in a school building, run by the city government.

It's home to 380 migrants and I spoke to dozens of men and women there and the one question they all want answered is: "When can I go home?"

Among them is Manoj Ahirwal, who's been at the shelter with his relatives since 29 March.

"The police told us they'll help us reach home, but they brought us here instead. They tricked us," he says, dejectedly.

The 25-year-old had arrived in Delhi from Simariya, his village 650km (400 miles) away, last month. The winter crop was coming up well, but there was still a month to go before harvesting.

So, he came to Delhi and joined his mother Kalibai Ahirwal and 21 other relatives on a construction site.

He had worked for just three days when India first announced the initial 21-day lockdown on 25 March.

Several hundred migrants were rescued from under a bridge along the Yamuna river in Delhi

With their livelihood grinding to a halt and meagre savings running out fast, they decided to return to their village.

But with train and bus services halted and state borders sealed, that wasn't really an option.

On 28 March, they heard the government was arranging buses to transport those stranded on the state border and set off for the Anand Vihar bus station.

But by then, the buses had left and there were thousands like them still stranded. In desperation, they decided to walk home.

"We bought 10kg (22lbs) wheat flour, some potatoes and tomatoes. We thought we'd stop by the roadside every night and cook," Kalibai Ahirwal told me when I met her at the shelter.

At this three-storey school, iron cots or mattresses have replaced desks and benches in classrooms and the authorities are providing three cooked meals every day. There's milk for children and occasional fruit for pregnant women.

The Ahirwals say they are grateful for the facilities, but are desperate to leave.

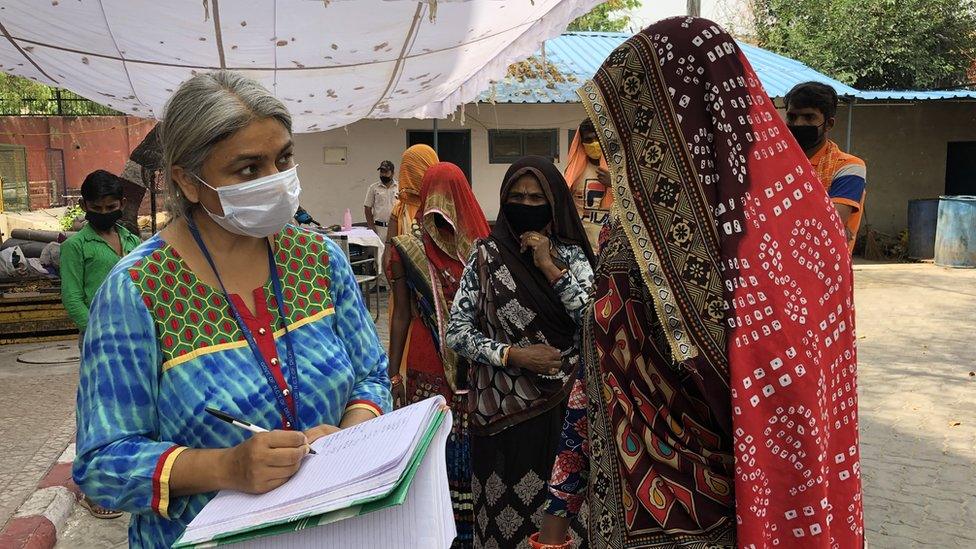

Health official Neelam Chaudhary checks all the migrants for fever every morning at this Delhi government shelter

The wheat crop in their village is ready to be harvested and Manoj Ahirwal says his father and elder brother, who are back home, can't manage on their own.

"This is the time we grow food for the whole year. The government will feed us for two-three months, but what will happen after that?" asks Kalibai Ahirwal.

Mr Modi announced the lockdown with barely four hours' notice. The decision unleashed chaos that India is still struggling to deal with.

Within hours of his announcement, millions of migrants began fleeing the cities, the key highways filled with men, women and children, carrying their belongings, trying to walk home, sometimes hundreds of miles away. Several people died in the process.

The authorities say the lockdown is key to saving lives, but the lack of planning has hit the country's poorest and most vulnerable citizens hard.

In the absence of work, many migrant workers are now dependent on food handouts from governments or charities for survival- some reduced to begging.

Rickshaw puller Sarathi Sarkar, who lives under a river bridge in Delhi, says in the absence of work, he's dependent on food handouts for survival

And as I write this story, reports are coming in about a 12-year-old girl who died after walking 150km from the southern state of Telangana to Chhattisgarh state in central India. She had walked for three days when she died, 14km from home.

"This lockdown is totally inhuman," lawyer-activist Prashant Bhushan, who has filed a petition in the Supreme Court asking for migrants to be allowed to return home, told the BBC.

"Those who test negative for Covid-19 must not be forcibly kept in shelters or away from their homes and families against their wishes. The government should allow for their safe travel to their hometowns and villages and provide necessary transportation for the same," the petition says.

If it goes through, it would help the Ahirwals and all the others being held at the Delhi government shelter.

"Since 29 March when the shelter was set up, all the 380 people have been checked every morning by health staff for fever and there hasn't been even one positive case," health official Neelam Chaudhary told me.

A SIMPLE GUIDE: How do I protect myself?

AVOIDING CONTACT: The rules on self-isolation and exercise

HOPE AND LOSS: Your coronavirus stories

VIDEO: The 20-second hand wash

Authorities say they are looking after 600,000 migrants in shelters while food is being provided to 2.2 million more. But millions are yet to receive any help.

"There are two types of stranded, the visible and the invisible," Anindita Adhikari, of the Stranded Workers Action Network (Swan), says.

"Those who are in shelters are visible. But there are a large number of people who are not in shelters. They live under the flyovers and sleep on footpaths, or stuck in workplaces, labour camps or slums."

Mr Bhushan says the condition of the shelters are also uneven. "In some feeding centres, people have complained of 2km-long food queues and there have been stampedes over food running out."

The desperation of the migrants is borne out by the fact that many continue to attempt fleeing the cities.

Earlier this month, police recovered 61 people from a truck meant to be transporting daily needs in Mumbai. Last week, a similar incident was reported from the north-eastern state of Assam involving 51 migrant workers. And a few days back, 11 migrants were caught in Gurgaon, a Delhi suburb, trying to flee in two ambulances.

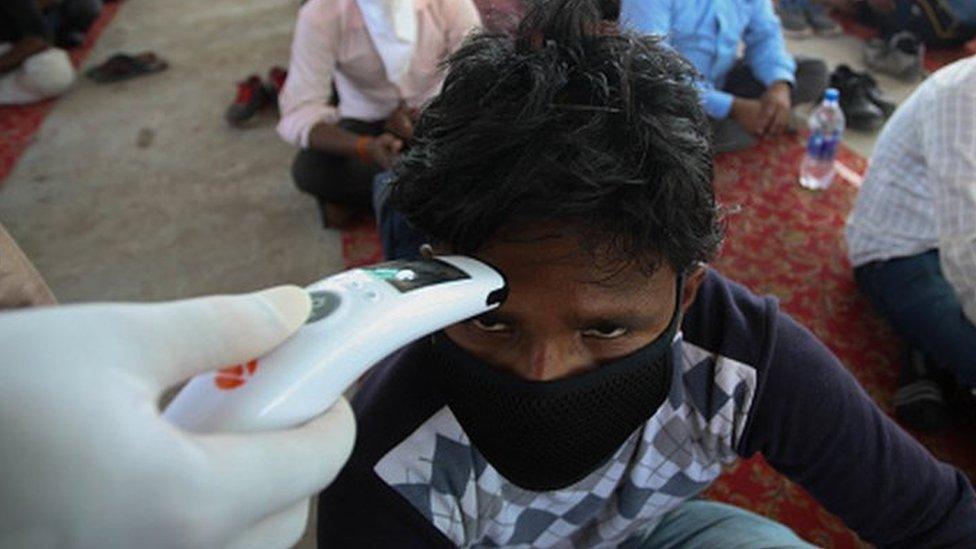

Millions of poor Indians are stranded far away from home, with no jobs or money

Over the past three weeks, Swan has received more than 11,000 distress calls from stranded workers, external and revealed its findings in a report.

"Most said they had ration for one or two days, many said they were eating one meal a day to conserve food. We found that 89% had not been paid their wages and most had just about 200 rupees ($3 ;£2) left," Ms Adhikari says.

"With neither food nor cash, migrant workers have been pushed to the brink of starvation, alarming levels of vulnerability and extreme indignity."

Mr Bhushan says the only solution to the problem is through cash transfers to the poor by the government.

"The government says employers should not stop wages of labourers. But how can small shops or businesses pay their workers when their own survival is at stake? And what about those who are self-employed, like street vendors?"

Lockdown, Mr Bhushan says, is not the solution, and imposing Section 144 of the Indian Penal Code, which prohibits gathering of more than four people, is a better idea.

The long-term impact of the shutdown, he says, will be lots of starvation deaths, destitution and penury.

"All the poor and lower middle classes will be in long-term misery. The economy is devastated.

"By shutting everything down, you may be able to save 100,000 lives, but if the lockdown continues, you'll kill one million from hunger and starvation."

- Published15 April 2020

- Published15 April 2020

- Published30 March 2020