Gulshan Ewing: Iconic editor dies of coronavirus in London

- Published

Gulshan Ewing's daughter says Gregory Peck was her favourite Hollywood actor

A pioneering Indian journalist who mingled with some of the world's most famous celebrities has died with Covid-19 at a home for the elderly in London.

Gulshan Ewing was 92 when she died in residential care in Richmond, her daughter Anjali Ewing told the BBC.

"I was right by her side when she stopped breathing." Despite her age, her mother had no pre-existing conditions, she says.

Ewing, who edited two of India's most popular publications - women's magazine Eve's Weekly and film magazine Star & Style - from 1966 to 1989 was a celebrated editor, and a celebrity in her own right.

In his book India: A million mutinies now, Nobel laureate VS Naipaul describes her as "India's most famous female editor".

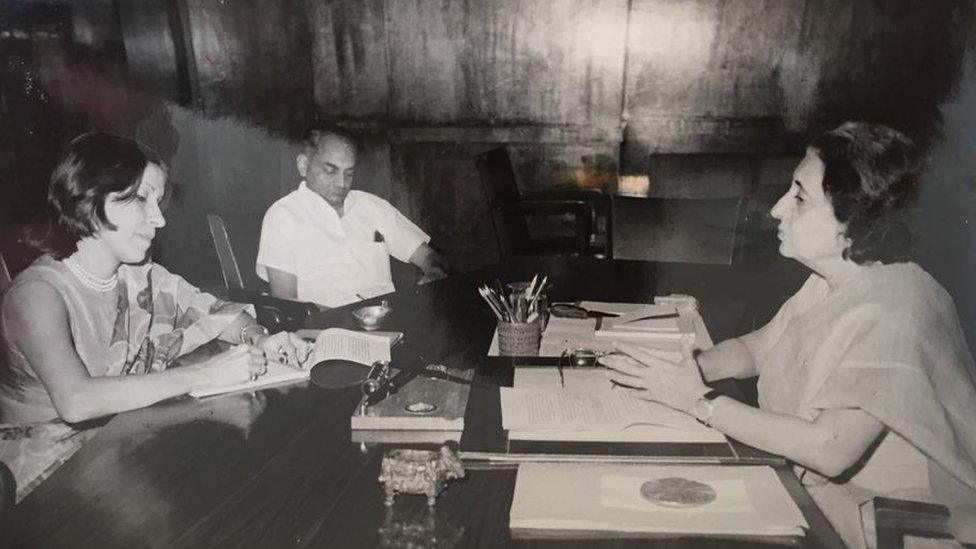

She also holds the record for the longest-ever interview that Indira Gandhi, India's first and only female prime minister, gave to any journalist.

Gulshan Ewing interviewed prime minister Indira Gandhi for her magazine

As the editor of Eve's Weekly, she mentored young female journalists and, as the feminist movement began to grow in India in the 1970s and 80s, led the magazine through changing times.

As the editor of Star and Style, she rubbed shoulders with the best of Hollywood and Bollywood, interviewing some of the biggest stars, writing about them and even partying with them.

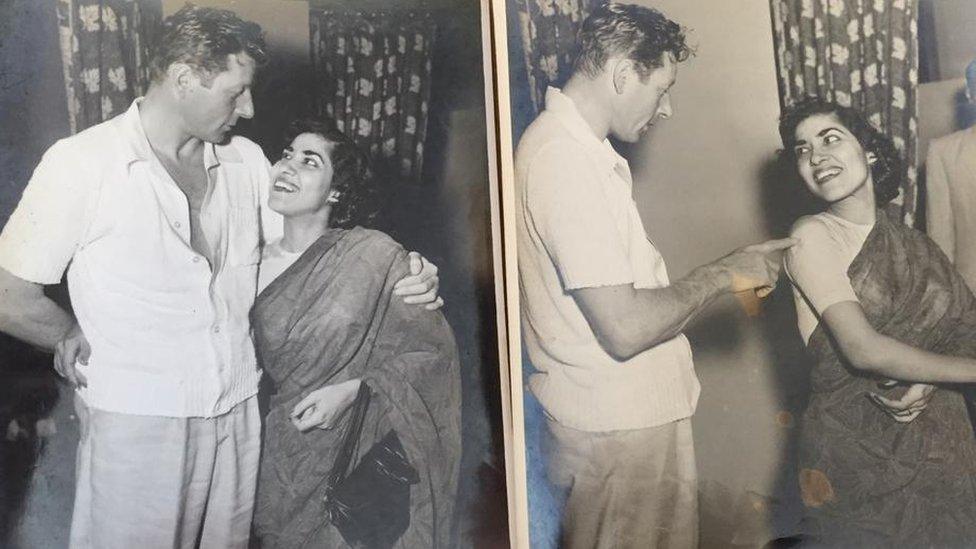

In the past week, news websites have published her photographs interviewing Hollywood legends Gregory Peck, Cary Grant and Roger Moore; she's seen dining with Alfred Hitchcock, chatting with Prince Charles, posing for photographs with Ava Gardner and teaching Danny Kay how to drape a sari.

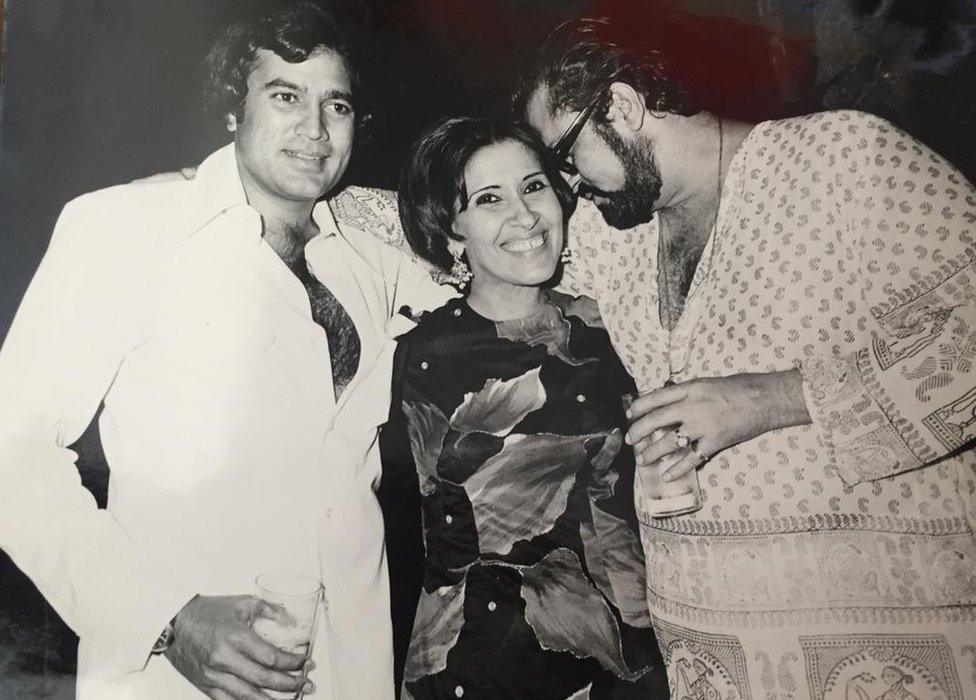

In Bollywood, says her daughter, her friendships ran deep - she dropped in on the sets of superstar Rajesh Khanna, partied with legends like Dilip Kumar, Shammi Kapoor, Dev Anand, Sunil Dutt and Nargis, and even danced with "biggest showman" Raj Kapoor.

She used to love mimicking Cary Grant's accent and would speak a few sentences in his style

Born to Parsi parents in Mumbai (then Bombay) in 1928, Ewing was among the first of a few women to join journalism in independent India. She worked for a number of publications before she was appointed editor of the two magazines. In 1990, she moved to London with her husband Guy Ewing, a British journalist she married in 1955. The couple have two children - daughter Anjali and son Roy.

Her death comes amid growing concerns over how Britain is handling Covid-19 infections in care homes. The virus has killed thousands of elderly and vulnerable people.

Ewing had been ill for a week and died peacefully on 18 April. Her test result, confirming the coronavirus infection, came a day later.

"I spent several hours sitting with her. I held her hand, I chatted, I spoke about the family, I told her how much I loved her," Anjali says.

"She was semi-conscious, she didn't speak. I played her favourite music, a couple of old Bollywood songs and Blue Danube."

Ewing, seen here with Rajesh Khanna and Shammi Kapoor, was close friends with many stars

She met Bollywood superstar Amitabh Bachchan many times

As news of her death came in, some of India's best-known female journalists who had worked with her 35 or 40 years ago, began fondly remembering an editor who gave them their first break, held their hands in their first jobs, was always kind and never condescending.

"She was my editor on my very first job, hiring me after a brief interview in her office in the 1980s," Charu Shahane, who's now a BBC World Service colleague in London, told me recently.

"In those days, I was very shy and tongue-tied. She was a known figure so when I got called for an interview, I was very nervous. But she immediately put me at ease."

She remembers Ewing as "an amazing, larger than life" editor, "a gorgeous and elegant figure, always impeccably dressed, with a touch of glamour, in chiffon saris and chunky pearl necklaces, with a cigarette dangling between her fingers".

Danny Kaye was very curious about how she tied her sari so she showed him how to drape it

Gulshan Ewing with Alfred Hitchcock

Ammu Joseph, who was an assistant editor in Eve's Weekly for four years, says Gulshan Ewing didn't walk into the office, she used to "swish into the office".

"We had a crammed space, it was a tiny office and she had a small cabin, but it looked spectacular because of who she was and her manner of speaking. She was elegant, soft-spoken, so sophisticated."

When Ms Joseph joined the magazine in 1977, the women's movement was just beginning to pick up in India and the campaign against dowry deaths - young brides being killed for bringing in insufficient dowry - was building up.

Gulshan Ewing was very close with actor couple Sunil Dutt and Nargis (right)

"I was 24 and I was all fired up with feminist ideas," she says. Most of her colleagues were of a similar age and disposition.

But Eve's Weekly was a traditional women's magazine with the "usual ingredients" like recipes, fashion and beauty tips, and knitting patterns. The cover always featured images of aspiring models and glamorous actresses.

"But to her credit, Mrs Ewing was open to the idea of making it more contemporary, more feminist. She enabled it."

So, the young journalists wrote about domestic violence and child abuse, the magazine had a special issue on rape, including marital and custodial rape, and a provocative article on misogyny in Hindu religion - all pretty revolutionary stuff considering the stigma that still surrounds these subjects in India.

"We pushed for change. We were in our 20s, she was in her 50s. She didn't have to listen to us, but she did."

She met Prince Charles during a visit to Mumbai

Pamela Philipose, who also worked as an assistant editor at Eve's Weekly in the 1980s, says Ewing "was almost intuitively able to grasp that the changing times required a feminist sensibility".

But, Ewing herself, she says, never wrote on topics like gender equality and violence against women "and enjoyed socialising with the beautiful people".

She did socialise with the beautiful people, but it was not something she made a big deal of.

In a tribute to Gulshan Ewing, her former colleague Sherna Gandhy says the photographs published in the past few days of her with Hollywood stars and British royalty "have come as a surprise to many of us who worked with her since she never boasted of her celebrity status, external".

Anjali, her daughter, who is also a journalist, says she knew she had "a famous mother, but for me she was mum; she was devoted to her family and paid a lot of attention to her husband and children".

Bollywood legend Raj Kapoor, a personal friend, dancing with her at an event

While growing up, she remembers her mother always brought home lots of work.

"For over 20 years, she was planning and commissioning for two magazines and it was a lot of work.

"She had film stars call her at 2am to complain about something that was written about them in the magazine and she would be on the phone for an hour, trying to placate them."

After she retired to London in 1990, Ewing took a complete break from writing and journalism.

Anjali says she suggested that she write a book, but she didn't seem too keen on it.

"That was her life then, and this was her life now. She divided work as hers, and family as ours.

"I think mum was a very lucky woman, she had an amazing career, and she was loved and adored by her husband. It sounds funny to say it, but she had it all."

A SIMPLE GUIDE: How do I protect myself?

AVOIDING CONTACT: The rules on self-isolation and exercise

HOPE AND LOSS: Your coronavirus stories

VIDEO: The 20-second hand wash

- Published15 May 2020

- Published28 April 2020