Amphan: Why Bay of Bengal is the world's hotbed of tropical cyclones

- Published

The Bay of Bengal, notes historian Sunil Amrith, is an "expanse of tropical water: still and blue in the calm of January winter, or raging and turbid at the peak of the summer rains".

The largest bay in the world - 500 million people live on the coastal rim that surrounds it - is also the site of the majority of the deadliest tropical cyclones in world history.

According to a list maintained by Weather Underground, 26 of the 35 deadliest tropical cyclones in recorded have occurred here.

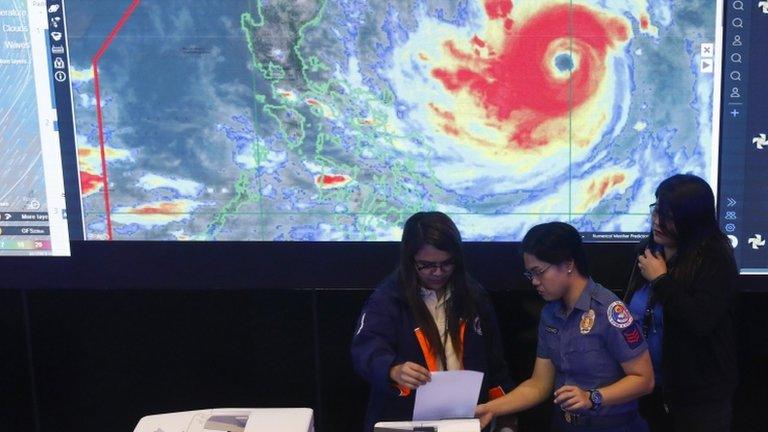

Cyclone Amphan is the latest, expected to make landfall in coastal areas of India and Bangladesh on Wednesday afternoon.

India meteorological officials say it will be an "extremely intense cyclone" when it hits the coast of the bay, with wind speeds up to 195km/h (121mph) and storm surges as tall as a two-storey building.

What makes the Bay of Bengal so deadly?

The worst places for storm surges, say meteorologists, tend to be shallow, concave bays where water, pushed by the strong winds of a tropical cyclone, gets concentrated or funnelled as the storm moves up the bay.

The Bay of Bengal is a "textbook example of this type of geography", Bob Henson, meteorologist and writer with Weather Underground, told me.

What makes matters worse are high sea surface temperatures in the Bay of Bengal, which can trigger extremely strong cyclones. "It is a very warm sea," says M Mohapatra, head of India's meteorological department.

Cyclone Fani made landfall in eastern India in May 2019

There are other coastlines around the world which are vulnerable to surging storms - the Gulf Coast of Louisiana, for example - but the "north coast of the Bay of Bengal is more prone to catastrophic surges than anywhere on Earth", says Mr Henson. The highly populous coastline also exacerbates the threat: one in four people in the world live in a country that borders the bay.

Why is there rising concern over Amphan?

For one, it has been designated as a super cyclone where wind speeds cross 220kmph (137mph). Cyclones are "multi-hazard" occurrences: strong winds cause physical damage; and tidal waves and heavy rains cause flooding.

This time round there is the coronavirus pandemic to contend with too - social distancing protocols to curb the spread of infection mean more shelters are needed, and thousands of migrant workers displaced by lockdown restrictions in India are on the move, many heading by foot to coastal villages.

Only a handful of storms in the Arabian Sea and Bay of Bengal - about one every 10 years - achieve the level of super cyclone.

In November 1970, Cyclone Bhola, the deadliest storm in world history, occurred in the Bay of Bengal and killed an estimated half a million people. It brought a storm surge estimated at 10.4m (34 feet) to the coast.

Dr Amrith, who teaches at Harvard University, says the frequency of intense cyclones has risen in the Bay of Bengal in recent decades.

At least 140,000 people died and two million people were displaced when Cyclone Nargis struck the Irrawaddy Delta in Burma (Myanmar) in May 2008. "It seemed as if a bucket of water had been sloshed across an ink drawing; the carefully marked lines [of the delta's waterways] had been erased and the paper beneath was buckled and distorted," one journalist wrote about the calamity.

The last super cyclone to hit India occurred in 1999 and caused nearly 10,000 deaths in Orissa (Odisha) state. I remember rotting corpses in ditches and smoke from funeral grounds clouding the skies, external as I travelled through some of the worst affected areas. That was when I first realised the untrammelled fury of a super cyclone in the Bay of Bengal.

- Published14 September 2018

- Published19 May 2020