Mumbai: How Covid-19 has ravaged India's richest city

- Published

Mumbai: Patients share beds in overrun Indian hospital

With more than 31,000 cases, Mumbai accounts for more than a fifth of India's coronavirus infections and nearly a quarter of deaths. The BBC's Yogita Limaye finds out why India's financial capital is so badly affected.

Mumbai has long been described as a city always on the run. It sounds like a cliché, but as someone who has lived here most of my life, I can confirm it's true. Even during the 2008 attack, on a day when there were active gunmen in south Mumbai, in other parts of the city, trains were running, millions went to work, and restaurants and offices remained open.

But Covid-19 has turned the city into a ghost town as a stringent lockdown remains in place with no easing of restrictions.

It has also left its medical infrastructure on the brink of collapse.

"Last night in just six hours I saw 15 to 18 deaths all from Covid-related causes. Never before have I seen so many people dying in a single shift," a doctor from KEM hospital - one of the many government institutes treating coronavirus patients - told me.

He refused to be named for fear of repercussions.

"It's a war zone. There are two to three patients per bed, some on the floor, some in corridors. We don't have enough oxygen ports. So even though some patients need it, they can't be given oxygen."

A doctor at Sion Hospital, another government facility, said they are splitting one oxygen tank between two or three patients. The space between beds has been reduced to accommodate more people. He added that there was no proper hygiene in areas where Personal Protection Equipment (PPEs) is worn and taken off.

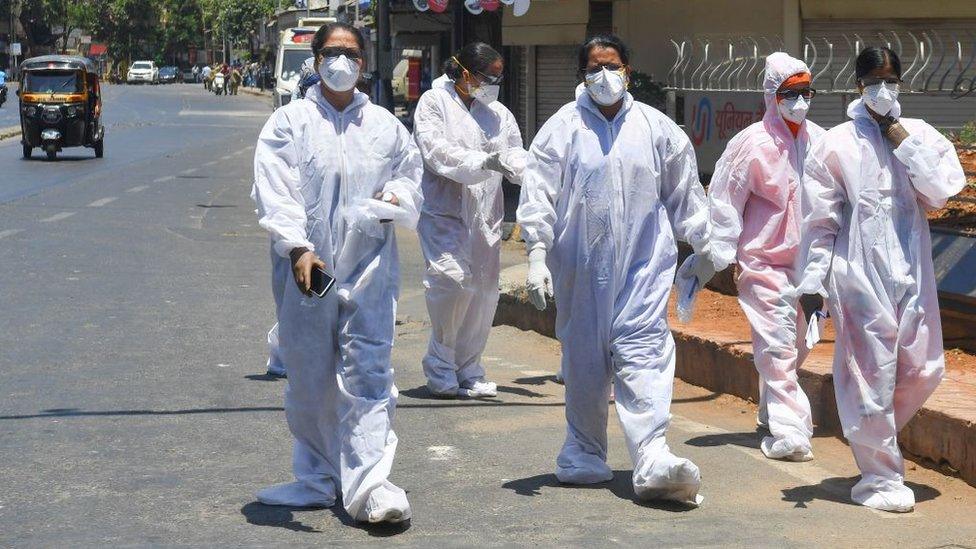

In Mumbai's hot and humid weather, doctors are drenched in sweat within minutes of wearing the kits.

Videos from both Sion and KEM hospital, showing people being treated next to dead bodies, and wards overflowing with patients, have caused a furore on social media.

"Mumbai has some of the finest health facilities and doctors. But it was not prepared for a pandemic," Dr Swati Rane, a public health expert in Mumbai, says. "The city of dreams has become a city of nightmares."

Mumbai is known as the city that never stops - but coronavirus has stopped almost everything

The economic powerhouse of India, a city stitched together from smaller islands, surrounded by the Arabian sea on most sides, Mumbai has attracted millions from all over the country in search of work and opportunities.

One of the reasons it faces such a tough battle against the virus is its population density - the second highest in the world according to a WEF report, external.

"The conditions highlighted in the videos have existed for years now," a doctor at one of the hospitals said. "Sadly, it has taken a pandemic for people to realise our healthcare system is bursting at its seams."

According to a government report, external, Mumbai has 70 public hospitals with a capacity of 20,700 and 1,500 private facilities with 20,000 beds. The city has roughly one bed per 3,000 people, well below the WHO recommendation of a bed per 550 people.

Mumbai's population has expanded rapidly since this estimation 10 years ago. But the health infrastructure has not kept pace.

Government doctors have been stretched particularly thin by Covid-19 because they have been bearing a disproportionately large burden.

"The whole load came on the crippled public sector. The private sector is hardly involved - only a few of their beds are being used for Covid-19," Dr Rane said.

Wearing PPE kits in Mumbai's hot and humid weather takes a toll on medical personnel

Last week the government of Maharashtra state, of which Mumbai is the capital, said private hospitals would have to dedicate 80% of their resources to treat Covid-19 patients, while prices would be capped.

"There was some reluctance at the beginning because of the nature of the infection," Dr Avinash Bhondwe, the Maharashtra president of the Indian Medical Association, a body that represents many private practitioners, said. "Now, around 3,000 independent doctors have signed up so far to help out. But we need PPE from standardised providers at standardised rates, which has not yet been made available to us."

But these private doctors are still to be inducted, and so far there is no relief for most government facilities.

"Help is urgently needed. We are working without any days off, or any time to quarantine ourselves," a Sion hospital doctor said on Monday.

Field hospitals that can accommodate around 4,000 patients are being built in many parts of the city, and a dashboard is being made to show which hospital has free beds.

But these moves are coming too late for some families.

Mumbai has close to 30,000 confirmed cases of Covid-19

Nithyaganesh Pillai says when his father started getting breathless, more than eight private hospitals, including some large facilities, turned him away. Finally, he took him to Sion Hospital.

"There was one stretcher which had blood stains on it. I somehow found a wheelchair and took my father inside," he said. "They told me he needed an ICU, but their beds were full. By the time a doctor examined my father, I was told he was barely alive."

A few hours later, 62-year-old Selvaraj Pillai died. His test result, which came after his death, confirmed Covid-19.

Nithyaganesh is in quarantine with his mother. "Every day I used to watch the news about coronavirus. I never imagined in my wildest dreams how it will affect me and my family. We are an upper middle-class family. You might have wealth, but it won't save the lives of your loved ones," he said.

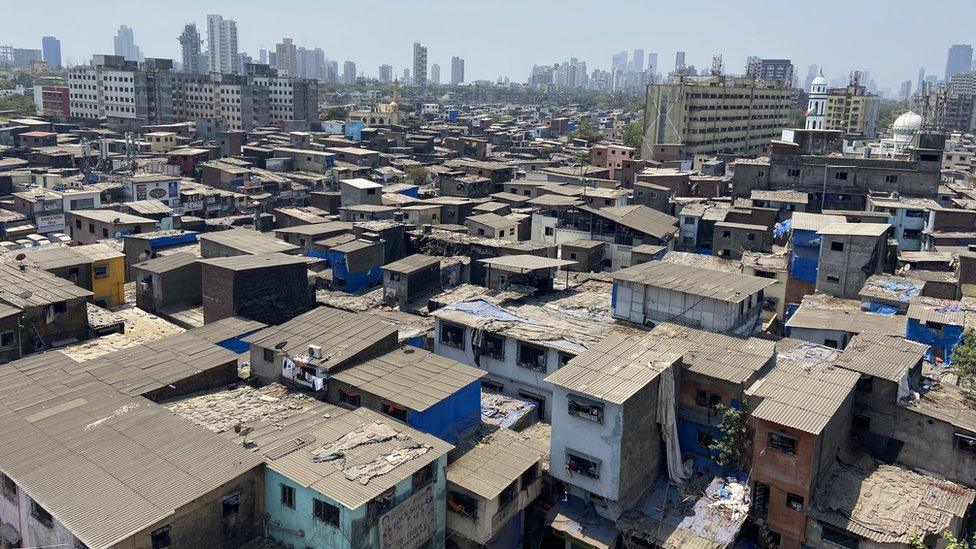

And in slum areas like Dharavi, life is even harder. Nearly a million people live in less than one square mile, which is more than 10 times the population density of Manhattan, New York.

"Fifty people use one bathroom. Ten to 12 people live, eat and sleep in tiny rooms. How can there be social distancing?" asked Mohammad Rahman, a resident of Dharavi.

The population density in Dharavi is more than 10 times that of Manhattan

He's part of an organisation that has been distributing food to thousands of workers in Dharavi left jobless because of the lockdown. "I have never worked so hard or felt so exhausted in my life. Now we have to stop giving food because we have run out of funds. How long can we sustain it?"

Personally, before the lockdown, I used to wake up to the sound of honking from the street below my house, and pass at least two dozen people on my short walk to work.

The emptiness is beautiful, of course. Every day we have clear, blue skies and there's been a surge in the number of flamingos visiting the city's creeks this year.

But the economic reality of the shutdown is terrifying.

Authorities are trying to take the burden off hospitals by building field units like these

The losses are running into billions of dollars. And with coronavirus cases rising, there's no end in sight.

"We can keep building new facilities. They will get full in a day. Unless we find the source of the spread of the virus and curb it, the city will have to remain under lockdown for months to come," warns Dr Rahul Ghule, who has been working with the municipal corporation to conduct door to door thermal screening in congested parts of the city.

Iqbal Chahal, Mumbai's municipal commissioner, says they've launched a programme called 'Chase the Virus' this week, which aims to aggressively trace the spread of the infection. "In slum areas, we will now be quarantining as many as 15 high risk contacts of a confirmed Covid case. So far we have screened 4.2 million people in Mumbai."

But another threat is looming.

The monsoon is fast approaching, and with it comes the risk of other illnesses including malaria, typhoid, gastric infection and leptospirosis. The work of essential services will be even harder during the rainy season.

- Published25 May 2020

- Published21 May 2020

- Published19 May 2020