Coronavirus: The 'tin pot' RWA dictators running life in India's cities

- Published

Major Atul Dev, a retired Indian army veteran, is on the warpath - against his Residents' Welfare Association.

Commonly known as the RWAs, these associations are a unique feature of Indian urban living. They are responsible for managing the day-to-day affairs of specific residential areas and generally set guidelines - relating to issues like security - for people to follow. Its members are elected by those living in a housing society or a neighbourhood.

But ever since India went into a lockdown to halt the spread of coronavirus, many are being accused of overreach, although they say they are only acting in the interest of everyone's safety.

In recent days, the Indian press has used unflattering phrases such as "little Hitlers" and "tin pot dictators" to describe them.

Many RWAs have issued lists of dos and don'ts which run into several pages and some of their diktats have been so arbitrary that governments have had to step in to rein them in.

"It is true that some have behaved like small-time dictators, inventing their own rules, even ignoring government regulations when they regard them as too liberal," columnist Vir Sanghvi wrote in the Hindustan Times newspaper, external.

"Some won't allow delivery men. Others will throw out newspaper hawkers and so on. It may be a great democracy outside but within the colonies, it is often a dictatorship of pygmies," he added.

Major Dev says "every RWA thinks they have to put in place procedures that are more stringent than what's been prescribed by the government".

The 80-year-old lives in Sushant Apartments, a residential complex in Gurugram (formerly Gurgaon) - an affluent suburb of the capital, Delhi.

Residents and visitors have to undergo thermal screening before they are allowed to enter apartment complexes across India

His RWA has set several rules that have irked the residents - delivery of newspapers, groceries and medicines are permitted only up to the main entrance of the complex and no visitors are allowed.

"My son and his family live in the same complex, but they are in a different tower and my daughter-in-law says she's afraid to visit me because of the severity of the rules," Maj Dev says.

The biggest bone of contention in Sushant Apartments - just like in most other apartment complexes and neighbourhoods across Indian cities - has been over whether to allow the part-time domestic helpers in or not.

The affluent and the middle-class live in gated complexes with private security guards, while the staff come from cramped slum colonies where social distancing is often not possible.

Compared to the West, Indian middle class homes have few gadgets and house work is labour intensive - clothes are washed in buckets, dishes are cleaned manually, and floors are swept with brooms and swabbed with rags. So families are often dependent on domestic workers and want them back.

Most workers also want to return because they don't want to lose their jobs.

But many RWAs are reluctant to let them in because "they may bring in Covid-19 into our complexes too".

Sushant Apartments only allowed the cooks and cleaners to return on 23 May - nearly three weeks after the government said they could start.

And that too, only after each resident had filled out a form certifying that their help was "healthy and has no Covid-19 related symptoms".

"The form also says that in case my maid develops coronavirus later, I - her employer - will be held responsible," Maj Dev said, adding that he filled out the "illegal form" only so he could let his domestic helpers back in.

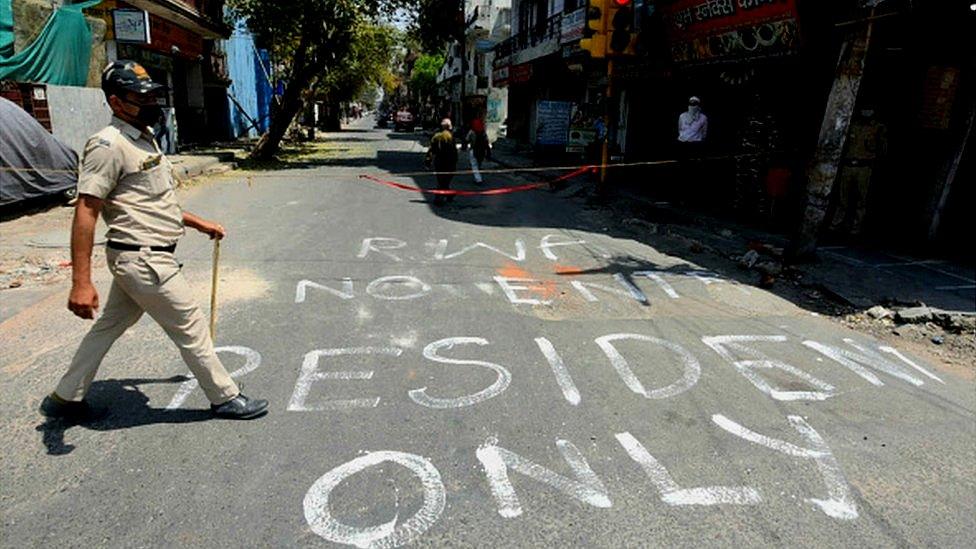

Residents of many areas have complained about locked gates and barricades that have popped up in the past two months

The RWA, he says, has also locked up the exit closest to their apartment block which means their domestic helpers have to take a circuitous route to get home.

"The shortest route is sealed up so the maids have to walk 2km instead of 200m to get to work at a time when the summer temperature is 45C or more," he says.

"They are also forced to walk through an area which has been declared a containment zone because of some positive cases there. This exposes them to the infection," he adds.

It's not just Gurugram. Complaints against unreasonable rules being imposed by the RWAs have come in from across the country.

Hitesh, who lives in the posh Defence Colony neighbourhood in Delhi, complained about "locked gates and barricades" that have popped up all around him in the past few months.

He's lived in Defence Colony all his life and knows the geography well, but says it has now become "a complete maze" and that if he had to "guide an Uber or a delivery guy to come to my house, I can't do it".

A friend from the southern city of Bangalore said his RWA stopped the newspaper delivery for two weeks after a video circulating on WhatsApp said papers could carry fomites and infect people with the coronavirus.

An upscale apartment complex in Gurugram asked the residents to pick up and drop their house help from the lobby so that they wouldn't have to touch the elevator buttons.

One woman wrote that her RWA had decreed that everyone had to "walk only in clockwise direction" in her apartment complex, and anyone walking anti-clockwise would be fined 500 rupees ($7; £5).

And a video posted on Twitter from a posh residential block in another Delhi suburb, Noida, showed a breathless domestic helper climbing up seven floors because the RWA would not allow her to take the lift.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

There were also videos that showed nurses and doctors being harassed by neighbours. Meanwhile, Air India, India's national carrier, had to issue an angry press release after some of its crew members who had travelled abroad to bring stranded Indians home were ostracised by "vigilante" RWAs.

In their defence, the RWAs say the restrictions are meant to protect the residents themselves from the pandemic.

There's no doubt that many residential societies are doing good work too - through the lockdown, most have organised supplies of essentials and ensured that streets are cleaned and garbage is collected.

In some places, they have also organised cooked meals and rations for migrant labourers and poor living in nearby slums.

"It's a tightrope walk," says Bhaskar Karmakar, who lives in a multi-storey complex in Bengaluru (Bangalore) and is also a member of the RWA.

"As a resident, I want my domestic staff to come to work. My wife and I have our office work, we have to do all the chores and also take care of our two teenage daughters. It's tough.

"But as a member of the RWA, I have to think this through. Sure you can get everyone in. But if one person gets Covid-19 and it spreads, then there's a problem."

There are people in the complex, he says, who are more vulnerable, such as the elderly, those with co-morbidities and young children, and they have to be protected.

"So it's not an easy choice. But it's better to be safe than sorry."

A SIMPLE GUIDE: How do I protect myself?

AVOIDING CONTACT: The rules on self-isolation and exercise

HOPE AND LOSS: Your coronavirus stories

VIDEO: The 20-second hand wash

- Published6 May 2020

- Published31 May 2020