Coronavirus: 'Our home turned into a hospital overnight'

- Published

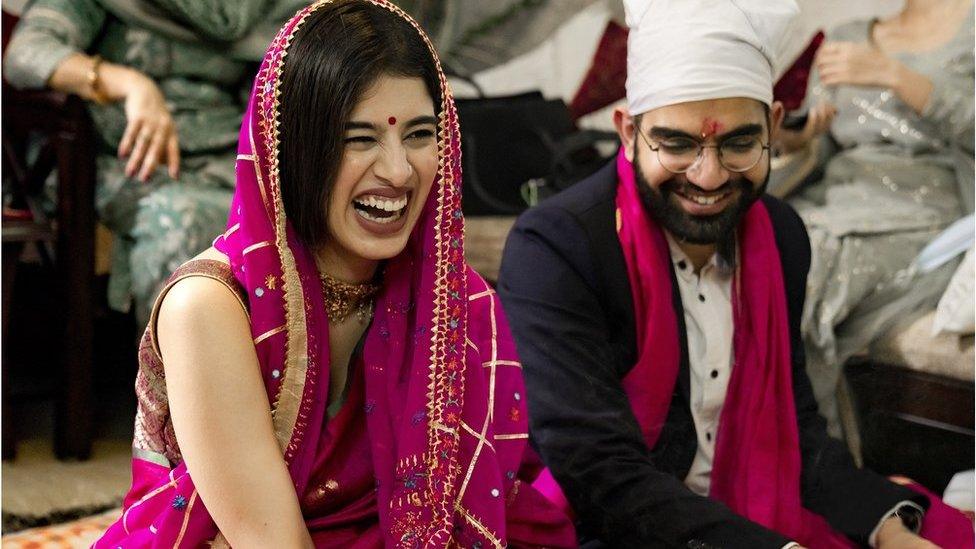

All 17 members of the Garg household

Mukul Garg wasn’t too worried when his 57-year-old uncle developed a fever on 24 April. Then, within 48 hours, two others in his family of 17 also became ill.

The symptoms trickled in as expected - temperatures spiked and voices grew hoarse with coughing.

Mr Garg initially chalked it up to seasonal flu, unwilling to admit it could be coronavirus.

“Five or six people often fall sick together in this house, let’s not panic,” he told himself.

Over the next few days, five more people in the house showed Covid-19 symptoms. And the pit in his stomach grew.

Soon, the Garg family would become its own coronavirus cluster as 11 of its 17 members tested positive.

“We met nobody from the outside and no-one entered our house. But even then the coronavirus entered our home, and infected one member after the other,” Mr Garg would later write in his blog, external, which has since attracted hundreds of comments from readers.

The exhaustive account shows how the multi-generational family, a mainstay of Indian life, poses a unique challenge in the fight against Covid-19.

The country's stringent lockdown, which began on 25 March and lasted until this week, focused on keeping people at home, off its busy streets and out of packed public spaces.

But in India - where 40% of households comprise many generations (often three or even four living together under one roof) - home is a crowded place.

It’s also vulnerable because research shows that the virus is more likely to spread indoors, external.

“All families under lockdown become clusters the moment someone is infected, that is almost a given,” says virologist Dr Jacob John.

And, as the Gargs discovered, social distancing isn’t possible within large families, especially during a lockdown when you are already cut off from the outside world.

‘We felt so alone’

The Gargs live in a three-storey home in a packed neighbourhood in north-west Delhi.

Mr Garg, 33, his wife, 30, and their two children, aged six and two, live on the top floor, along with his parents and grandparents.

On the two floors below them live his uncles - his father’s brothers - and their families. Members range from a four-month-old baby to a bedridden grandfather of 90.

Mr Garg's uncle may have caught the virus from a vegetable vendor

Contrary to cramped joint family homes where many people share a room and a bathroom, the Garg home is spacious. Each floor is about 250 square metres, roughly the size of a doubles tennis court, with three bedrooms, en suite bathrooms and a kitchen.

And yet, the virus spread quickly, travelling across floors and infecting almost all the adults in the house.

They identified patient zero - Mr Garg’s uncle - but the family is still not sure how he caught the virus.

“We think it could be from a vegetable vendor or from someone at the grocery store because that was the only time anyone from the family stepped outside,” he says.

But as the virus spread, fear and shame kept them from getting tested.

“We were 17 of us, but we felt so alone. We worried that if something happened to us, would anyone even come to the funeral because of the stigma associated with coronavirus?”

But in the first week of May, when his 54-year-old aunt complained of breathlessness, the family rushed her to a hospital. And, Mr Garg says, they knew they all had to get tested.

‘The month of the disease’

All of May was spent fighting the virus.

Mr Garg says he would spend hours talking to doctors over the phone, while everyone checked in on each other on WhatsApp daily.

“We also kept changing the position of the members depending on symptoms, so no two people with high fever were in the same room.”

Six of the 11 infected have co-morbidities - diabetes, heart disease and hypertension - which made them more vulnerable.

“Overnight, our home became a Covid-19 healthcare centre with all of us taking turns to play nurse,” Mr Garg says

Families are particularly vulnerable to widespread infection in a lockdown

Virologists say large families are like any other cluster, except for the range in ages.

“When you have a range of age groups sharing common spaces, the risk is disproportionately distributed, with the elderly at most risk,” says Dr Partho Sarothi Ray, a virologist.

This weighed heavily on Mr Garg, who worried about his 90-year-old grandfather.

But the virus, which continues to confound medical experts around the world, also held surprises for the Gargs.

It wasn’t unusual that he and his wife, both in their early 30s, were asymptomatic. But it was bewildering that his grandfather was also asymptomatic. And one member of the family, who had no comorbidities, was taken to hospital. The others showed typical symptoms.

Mr Garg says he wrote the blog because he wanted to reach out to people worried about seeking help.

“In the beginning, we cared so much about what people would think. And reading the comments, it’s so nice to see people saying it's ok if you get it, it’s not something to be ashamed of.”

In the second week of May, symptoms began to vanish and the family watched as more and more negative tests rolled in, bringing relief. This was also when Mr Garg's aunt was discharged from hospital after testing negative.

They finally felt like the worst was over.

By the end of May - “the month of the disease” as Mr Garg called it - only three people, including him, were still positive.

On 1 June, they got tested for the third time and the results came back negative.

‘Our best and worst’

India’s large families can be a source of support and care, but also friction and thorny property disputes. But at times like these they can also come to the rescue.

“Can you imagine an elderly person in quarantine all by themselves with no-one to help? Despite the challenges, joint families benefit from the young taking care of the old,” Dr John says.

Cases in India have sprinted past the 250,000-mark, spurring a debate over whether the pandemic could threaten extended families, external, as young people worry about carrying the infection home to older relatives.

India re-opened this week after a strict lockdown

“It's a system that has survived hundreds of years of an onslaught of Western values and colonisation,” says Prof Kiran Lamba Jha, who teaches sociology at Kanpur's CSJM university. “Coronavirus is not going to destroy the joint family.”

The Gargs would agree.

Before the virus struck, the family was thriving. It was almost reminiscent of a 90s Bollywood flick, Mr Garg says.

“As a family, we had never spent so much time together than we did that first one month of the lockdown. It was also the happiest the family had ever been," he says, adding that it only made it harder to watch as one person after another fell sick.

“We saw each other at our best and worst but we came out of it stronger,” he says.

“We’re still cautious about reinfection but right now, we’re basking in the glory that we managed to beat this virus and come out on the other side.”

- Published9 June 2020

- Published16 May 2020

- Published8 April 2020