Can India afford to boycott Chinese products?

- Published

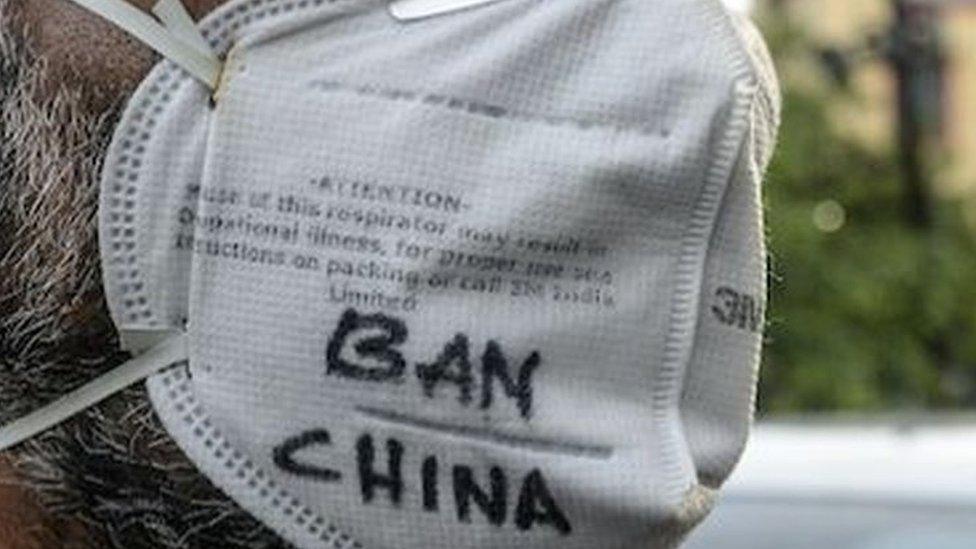

Indians have taken to the streets to protest against China

Anti-China sentiment has been on the rise in India since last week’s fatal border clash between the two nuclear-armed neighbours.

Twenty Indian soldiers were killed in fighting at a disputed border site in the Himalayan Galwan Valley, prompting a swift and theatrical backlash on India’s streets.

People in the western Indian city of Ahmedabad hurled Chinese TV sets down their balconies, while traders in the capital, Delhi, protested by burning Chinese goods.

A central minister called for a boycott of restaurants selling “Chinese food” - an Indianised version of Chinese cuisine that is hugely popular; an opposition leader was seen clambering atop a JCB machine to blacken a billboard of Chinese smartphone maker Oppo; a group of eager protesters went viral after burning an effigy of North Korean leader Kim Jong-un, mistaking him for Chinese President, Xi Jinping.

The Indian government hasn’t explicitly announced a boycott, but by all accounts states and public sector companies have been reportedly asked to desist from issuing new contracts to Chinese companies. The railways have reportedly cancelled a signalling project that was given to a Chinese company in 2016. And, according to reports, external, the government has also asked e-commerce companies to display the country of origin for the products they sell.

Bilateral trade between the countries, already down by 15% since the 2018 financial year, could take a further hit as India mulls extra tariffs and anti-dumping duties on Chinese imports.

But, experts warn, it’s easier said than done to convert such boycott rhetoric into reality.

What is the alternative to China?

For one, China is India’s second-largest trading partner after the US. And two, it accounts for nearly 12% of India’s imports across sectors such as chemicals, automotive components, consumer electronics and pharmaceuticals.

“At least 70% of India’s drug intermediary needs are fulfilled by China,” Sudarshan Jain, president of the Indian Pharmaceutical Alliance, told the BBC.

Although India has announced a new policy to become more self-reliant in drugs, he says that will take time.

The clash took place in Galwan Valley in the Himalayan region of Ladakh

India’s booming smartphone sector also heavily depends on cheap Chinese phones made by Oppo, Xaomi and others with the lion’s share of the local market.

Most consumer electronics makers say they’ll be paralysed if they can’t import crucial intermediate goods from China.

“We are not worried about finished goods. But most players across the globe import key components such as compressors from China,” says B Thiagrajan, managing director of Blue Star Limited, an Indian manufacturer of air conditioners, air purifiers and water coolers.

Mr Thiagrajan adds that it will take a long time to set up local supply chains, and that there are few alternatives for certain kinds of imports.

Chinese money funds Indian unicorns

India and China have also become increasingly integrated in recent years. Chinese money, for instance, has penetrated India's technology sector, with companies like Alibaba and Tencent strategically pumping in billions of dollars into Indian startups such as Zomato, Paytm, Big Basket and Ola. This has led to Chinese giants deeply "embedding themselves" in India’s socio-economic and technology ecosystem, according to Gateway House, a Mumbai-based think tank.

“There have been more than 90 Chinese investments in Indian startups, most of them made over the last five years. Eighteen out of 30 Indian unicorns [tech startups valued at over $1bn] have a Chinese investor,” says Amit Bhandari, an analyst at Gateway house.

At $6.2bn, direct Chinese investment in India appears relatively small. But, Mr Bhandari says, restricting the likes of Alibaba from creating monopolies in the Indian market will be crucial given the “outsized impact” of these investments.

To that effect, India has already amended its FDI (foreign direct investment) rules to stave off hostile takeovers of Indian companies.

While China has accused India of contravening WTO principles, it’s unlikely to cut ice under current circumstances "as there is no way of enforcing any decision if an inter-country conflict is cited as a reason to justify the violations”, Zulfiquar Memon, managing partner at MZM Legal, said in an email interview.

India's smartphone sales are driven by cheap Chinese manufacturers

This gives India some leeway to reduce its dependence on imports, and heed growing calls for self-reliance. India’s gaping trade deficit of nearly $50bn with China has long been a sticking point between the two countries, and the current standoff provides an impetus for India to shrink the gap.

Is self-reliance the answer?

India’s domestic manufacturing sector can substitute as much as 25% of total imports from China, according to new findings from Acuité, a ratings agency. This would lead to a reduced import bill of over $8bn in a single year.

Handicrafts, for instance, is a category where India imported $431m worth of goods from China in the 2020 financial year without any significant reciprocal exports.

But Mr Bhandari of Gateway House says boycotting popular Chinese apps such as TikTok might be more effective than boycotting physical goods in terms of value added because there are multiple alternatives.

Experts say the calls for boycott don't take into account the range of Chinese investments in India

But from India’s standpoint, none of this is likely to play out without grave consequences to the economy, especially during a severe downturn. China, on the other hand, is less concerned since India accounts for only 3% of its exports.

So far Beijing has been restrained in its reaction to the growing backlash in India.

But a recent op-ed in the daily Global Times warned that “China's restraint is not weak”.

It says it would “be extremely dangerous for India to allow anti-China groups to stir public opinion, thus escalating tensions”, and adds that the focus should instead be on “economic recovery”.

- Published18 May 2020

- Published30 May 2020