India coronavirus: How Kerala's Covid 'success story' came undone

- Published

Officials say community transmission is happening in some parts of Kerala

There's anxiety and confusion among people living in a bustling coastal village in India's southern state of Kerala these days.

The 4,000-odd families of Poonthura, a hamlet of fishermen next door to the capital city of Trivandrum, have been served with strict stay-at-home orders. Nobody can enter or leave the place. Businesses are shut and transport suspended. Commandos and policemen have patrolled the streets to enforce a stringent lockdown.

Earlier this month, more than 100 people in Poonthura's densely packed villages hugging the Arabian Sea contracted Covid-19 after some of them visited a fish market. This contributed to a sharp spike in infections in a state which, in May, appeared to have tamed the virus.

"People are confused, isolated and tense," Father Bebinson, the vicar of the local church, told me. "They can't make out what has suddenly hit them."

He's right. Barely two months ago, Kerala was looking like a striking outlier in the battle against coronavirus in India. But cases have surged in the last few weeks, and the state government is now saying the virus is locally transmitting through coastal communities, the first such admission by officials in any state since the beginning of the pandemic in India.

"The real surge in Kerala is happening now. The virus had earlier been curbed in a controlled situation when the state's borders were closed," Dr Lal Sadasivan, a Washington-based infectious disease specialist, told me.

In January, Kerala reported India's first Covid-19 case, a medical student who returned from Wuhan in China, where the pandemic began. The number of cases rose steadily, and it became a hotspot. But in March, half a dozen states were reporting more cases than the picturesque southern state.

By May, sticking faithfully to the contagion control playbook of test, trace and isolate and involving grassroots networks, Kerala brought down its case count drastically - there were days when it reported no new cases. "The mark of zero",, external The Hindu newspaper rhapsodized in an editorial about the containment effort. There were breathless stories about the state flattening the curve. "I remember saying that Kerala had achieved a viral miracle," says Jayaprakash Muliyil, a leading epidemiologist.

More than 200,000 Keralites working in the Gulf returned home after the lockdown

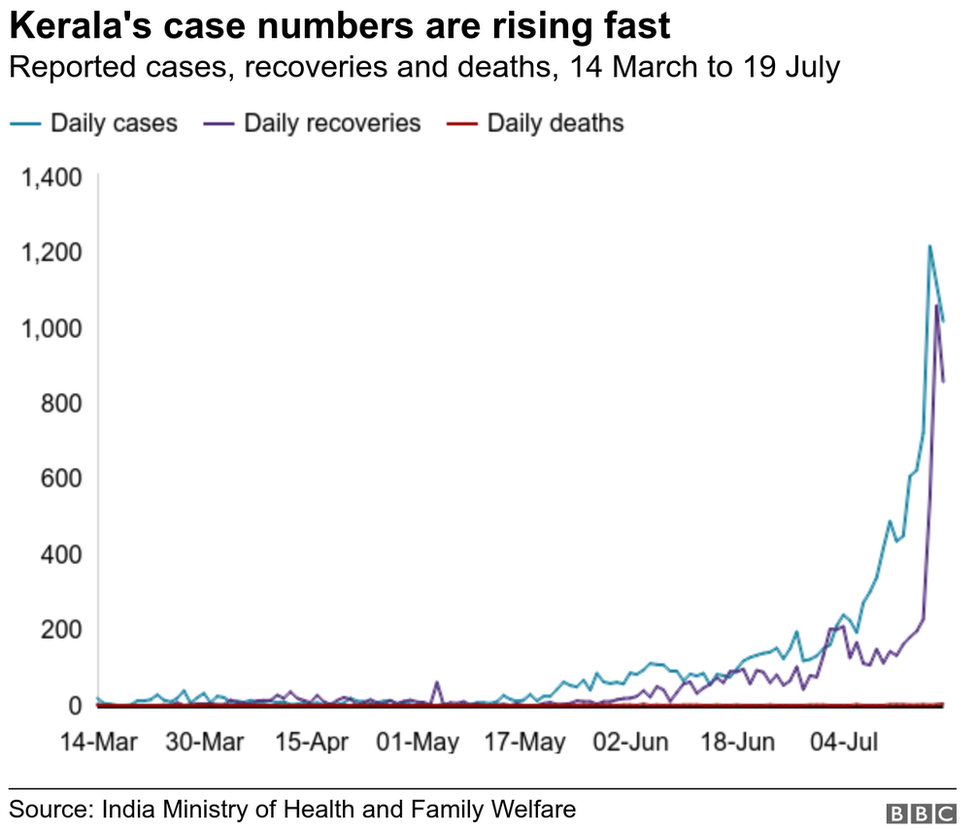

The celebrations were clearly premature. Kerala took 110 days to report its first thousand cases. In mid-July, it was reporting around 800 infections a day. As of 20 July, Kerala's caseload had crossed 12,000, with 43 reported deaths. More than 170,000 people were in quarantine, at home and in hospitals.

One reason, say experts, for this sharp uptick is that nearly half a million workers returned to the state from the Gulf countries and others parts of India after the grinding countrywide lockdown, which shut businesses and threw people out of their jobs. Some 17% of Kerala's working-age population works outside the state.

Unsurprisingly, more than 7,000 of the reported cases so far have a history of travel. "But when the lockdown travel restrictions were lifted, people came flocking back to the state, and it became impossible to curb the re-entry of infected cases," says Shashi Tharoor, a senior Indian opposition politician and member of parliament from Trivandrum.

Mr Tharoor remembers a conversation he had with Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan soon after the first repatriation flights carrying Keralites working in the Gulf countries landed in Kerala. "He lamented that not only the virus was coming in, but infected people were transmitting the contagion to fellow passengers on the plane."

"I think this was unavoidable, since every citizen has a constitutional right to come home to India, even if they are ill. But that made a major difference," Mr Tharoor told me.

The influx has possibly sparked a surge in local community transmission - since early May, reported cases without any travel history have gone up. More than 640 of the 821 new cases reported on Sunday, for example, were contracted locally, officials said. The source of 43 of them is untraceable.

The surge in cases is mainly confined to fishing communities

The easing of the lockdown led to many people moving out of their homes and not taking enough precautions. "Some amount of laxity was expected as people have begun going out to work in most areas. We are trying to motivate them to be safe," Dr B Ekbal, head of an expert panel advising the government on prevention of the virus, told me.

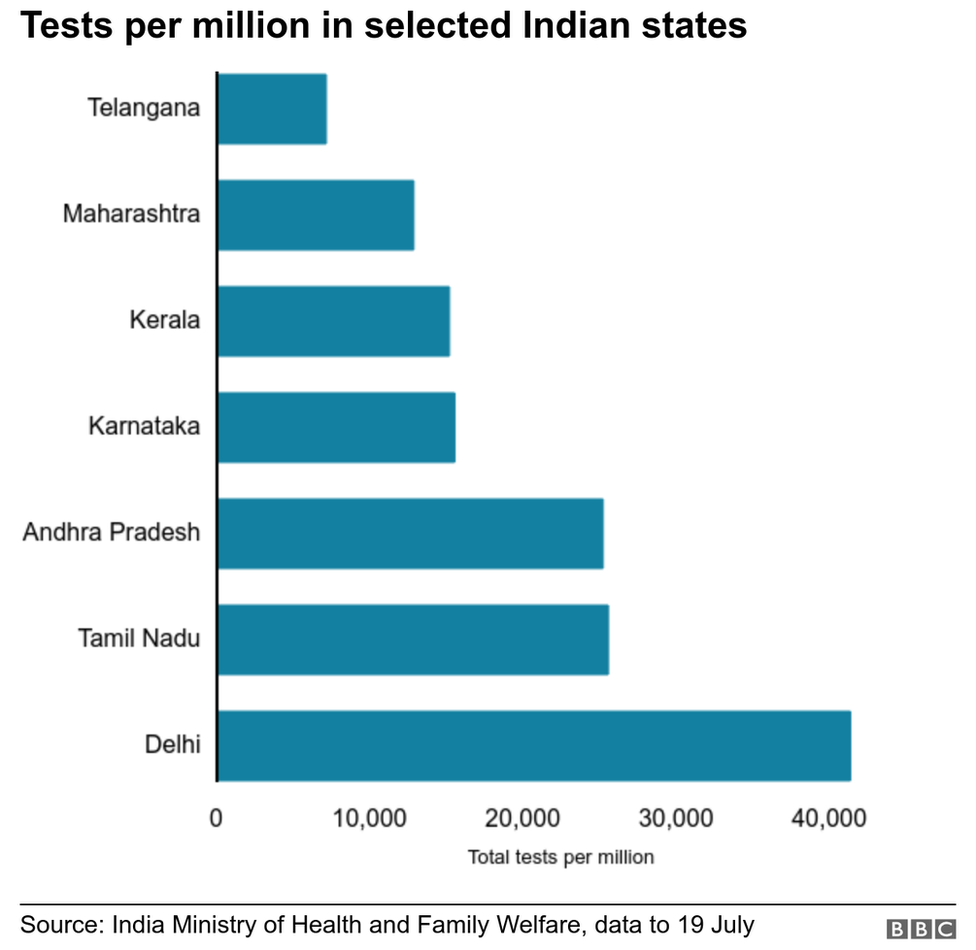

Some critics say testing slowed after the caseload fell in what they believe was a sign of complacency. These days Kerala is testing more than 9,000 samples a day, up from 663 in April.

Its testing rate per million of the population is lower than in states such as Andhra Pradesh, where cases are rising quickly as well, or Tamil Nadu, which has long been a hotspot. But it's ahead of Maharashtra, the country's biggest hotspot so far.

Kerala is doing a bouquet of tests - diagnostic, pooled, rapid antigen and antibody among others - but it is not clear how many cases are being detected by each of these tests. This is pushing up testing numbers, but possibly not reflecting the correct picture. "Testing has been ramped up. But it's never enough. No state is being able to test as widely as needed," says Dr A Fathahudeen, who heads the critical care department at Ernakulam Medical College.

Most epidemiologists believe Kerala has done a good job on the whole. The case fatality rate - the proportion of people who die among those who have tested positive for the disease - is one of the lowest in India. The hospitals are not yet overwhelmed by a surge of patients. The state boasts India's most robust public health system. The government has begun rolling out first line Covid-19 treatment centres with oxygen-equipped beds in hundreds of villages.

Kerala is also a cautionary tale against premature media declarations about the flattening of the curve, which involves reducing the number of new cases from one day to the next.

In May, Kerala was reporting no new infections for several days

Experts say flattening the curve is a long and tortuous journey. Gabriel Leung, an infectious disease epidemiologist at the University of Hong Kong, says "the restrictions must be lifted and reapplied, and lifted and reapplied,, external as long as it takes for the population at large to build up enough immunity to the virus".

T Jacob John, a retired professor of virology at Christian Medical College, Vellore, offers an interesting analogy. "Combating Covid-19 is like running on a treadmill whose speed is being cranked up. As the virus spreads you have to run faster to tame it. It's exhausting, but there is no other choice," he says. "It's a test of endurance".

- Published19 March 2020