India GDP shows worst quarterly slump in decades

- Published

India has seen huge job losses in recent months

India's economy contracted sharply in the three months to the end of June, official data shows.

It shrank by 23.9%, its worst slump since the country started releasing quarterly data in 1996.

The coronavirus pandemic and a grinding lockdown caused massive disruptions to economic activity during the quarter.

Experts fear that India is staring at a recession - that will happen only if it reports contraction in the next quarter as well, which experts say is likely.

A country is considered to be in recession if it reports contraction for two successive quarters. India was last in recession in 1980, its fourth one since independence.

India has been reporting record daily spikes in Covid-19 cases in recent days.

India has recorded more than 3.6 million Covid-19 cases so far - on Sunday it reported 78,761 new cases in 24 hours, the world's highest single-day increase.

But the country continues to reopen because, experts say, a second lockdown is economically unviable. And the effects of the first lockdown are evident in the latest GDP figures.

The numbers aren't surprising given that the lockdown was in effect for most of the quarter in question - April to June.

Figures don't reflect India's 'true economic distress'

By Nikhil Inamdar, BBC News' India business correspondent

While India's GDP saw the sharpest contraction on record, the number is expected to undergo further revisions as data collection was severely impaired during the lockdown.

The headline figure is at the upper end of what most analysts were estimating, but some have cautioned that in the absence of real time data, the number doesn't reflect the gravity of the economic distress.

From hotels to trade, electricity generation, manufacturing and construction, almost every segment of the Indian economy showed a sharp contraction during the first three months of the financial year. The only sector that posted positive growth was agriculture, at 3.4%.

By all accounts, a quick recovery is unlikely in India, and it is only in the last three months of the year that growth is expected to return to positive territory. Cases continue to spike and lockdowns are ongoing in several areas. As a result, consumer demand, which determines 60% of GDP, is unlikely to return in a hurry as most people are stepping out only to buy essentials.

"We expect further fiscal and liquidity stimulus," Abhimanyu Sofat, head of research at IIFL Securities, told the BBC. But with the government's tax and non-tax revenues down sharply and expenditure going up, the fiscal space to revive the economy remains limited.

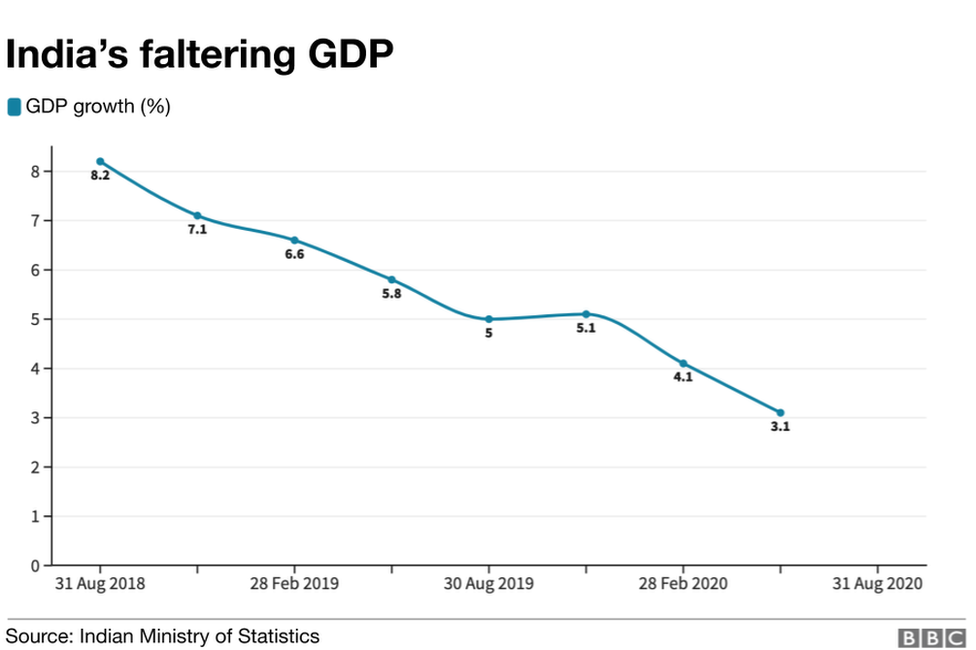

India's economy was already faltering when Covid-19 struck. Last year, unemployment touched a 45-year high and growth dipped to 4.7%, the lowest in six years. Output was shrinking as demand fell and banks were burdened by a mountain of debt.

Then came a global pandemic, which only worsened the situation. An unprecedented lockdown at the end of March forced many factories and businesses to shut temporarily, brining most economic activity to a halt.

One month into the lockdown, 121 million Indians had lost their jobs, according to the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE), an independent think tank.

Agriculture has fared better than other sectors

But CMIE also estimates that tens of millions of those jobs have since returned, mainly due to a resumption of economic activity as the country reopened from June onwards.

Experts, however, believe that many of these jobs are in the informal sector, largely agriculture, the mainstay of India's economy.

While most industries, from manufacturing to services to retail contracted, agriculture and agri-businesses have bucked the trend.

Exemptions from the lockdown, a bumper harvest and the delayed arrival of Covid-19 in rural areas seems to have helped.

- Published18 May 2020