India's Covid crisis sees rise in child marriage and trafficking

- Published

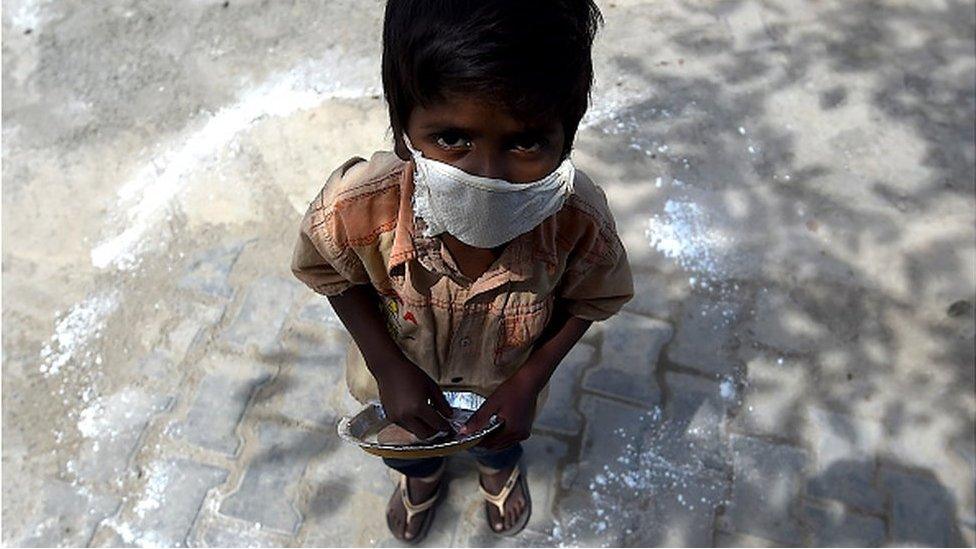

Complaints of child marriage and child labour have risen during the lockdown

India's coronavirus lockdown has had an adverse impact on children, pushing up incidents of child marriage and child labour, reports the BBC's Divya Arya.

Thirteen-year-old Rani has just won her first battle in life. Her parents tried to force her to marry this summer, but Rani reached out for help and managed to stop the wedding.

Rani (not her real name) was in the eighth grade when India's federal government suddenly imposed a lockdown in March, shuttering everything from schools to businesses to stop the spread of coronavirus.

Within a month, Rani's father, who was battling tuberculosis, found her a match.

Rani was not happy. "I don't understand why everyone is in a rush to marry girls," she said. "They don't understand that it is important to go to school, start earning and be independent."

It is illegal for girls under the age of 18 to marry in India. But the country is home to the largest number of child brides in the world, accounting for a third of the global total, according to UNICEF. The charity estimates that at least 1.5 million girls under 18 get married here each year.

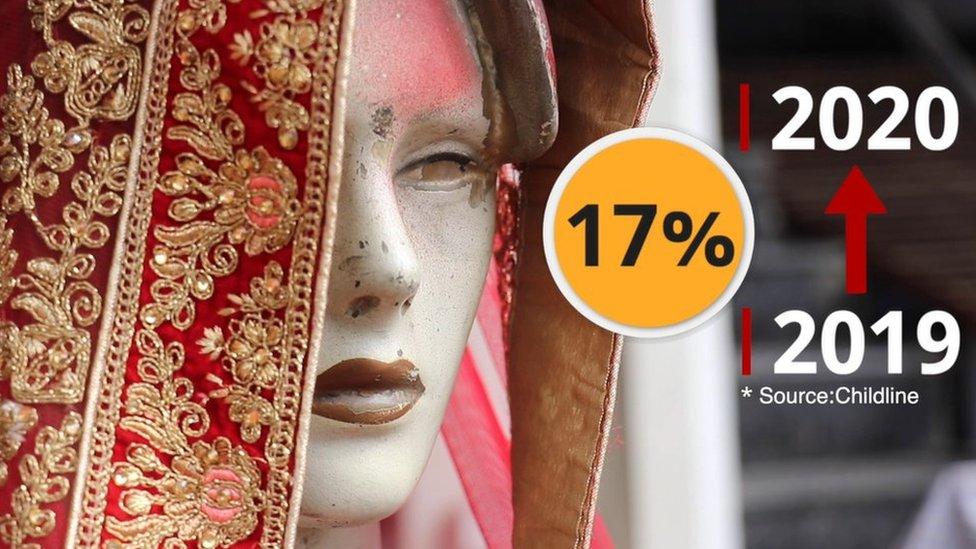

This year might be worse. Childline, a children's helpline, has reported a 17% increase in distress calls related to early marriage of girls in June and July this year compared to 2019.

Millions lost their jobs during the prolonged lockdown from the end of March to early June. Many of them included India's informal and unprotected workers, who, have been pushed deeper into poverty.

According to the government, more than 10 million of these works, many of them young men, returned to their hometowns and villages during the lockdown because of loss of work. So parents of young girls - worried for their safety and anxious about their future prospects - are marrying their daughters off to ensure their wellbeing.

Another reason is that parents are expected to pay for big weddings, but covid restrictions have limited the size of weddings.

So parents who have received offers of marriage this year have been quick to take them up, according to Manisha Biraris, the assistant commissioner for Women and Child Welfare in Maharashtra state.

"It was easier, cheaper and they could get away with inviting very few people."

Although the country began reopening in June, many jobs have not returned and the economy is still struggling. Schools are still shut, leaving vulnerable adolescents at home.

Schools have been agents of change in India, especially in poor communities like the eastern state of Odisha, where Rani lives. They are a space where girls can reach out to teachers and friends for help when facing pressure to marry from their family.

A child helpline has reported a rise in distress calls about child marriage

But with schools closed, a crucial safety net is gone.

"In extremely poor communities, girls are already not encouraged to study. Once they leave school it's hard to convince families to get them back in," said Smita Khanjow from Action Aid, which has been working on UNICEF's special program on child marriage in the five most-affected states.

Rani's close school friend was married off early this year, she said. But Rani said she was able to stop her wedding after she called the emergency national helpline for children, Childline. Along with the help of a local NGO and the police, staff at Childline were able to stop the ceremony.

But Rani's troubles didn't end there. Her father passed away soon after.

"I want to go back to school when it reopens, and now I need to work harder as my father is no more," she said. "It is my responsibility to help my mother run the household."

The situation has been dire for boys too. According to Ms Khanjow, from Action Aid. She and her colleagues are increasingly coming across cases of teenage boys being pushed into working in factories to support their families

In India, it is a criminal offense to employ a child for work. But according to the last census, in 2011, 10 million of India's 260 million children were found to be child labourers.

It's not an easy decision for families. Four months into the lockdown, Pankaj Lal gave in to a trafficker's offer for his 13-year-old son. He had five children to feed but almost no earnings from pulling his rickshaw.

Millions of children are illegally employed across India

Mr Lal agreed to send his son more than a 1,000km (690 miles) from his native Bihar state to Rajasthan to work in a bangle manufacturing factory for 5,000 rupees ($68; £52) per month. That is a substantial sum for a family struggling to survive.

Mr Lal broke down as he described his decision to send his son so far away.

"My children had not eaten for two days," he said. "I volunteered myself to the trafficker, but he said nimble fingers were needed for this work and I was of no use to him. I had almost no choice but to send my son away."

Despite restrictions on transport and movement, traffickers were able to tap into their powerful nexus to move children across state lines using new routes and luxury buses.

Suresh Kumar, who runs NGO Centre Direct, says a crisis is waiting to happen. He has been rescuing child labourers from traffickers for more than 25 years.

"The number of children we have rescued has more than doubled from last year. Villages have emptied out and the past months have seen the traffickers grow stronger and make use of the lockdown which has stretched authorities and the police," he said.

Childline, however, reported a drop in distress calls related to child labour. Activists say this could be because children give in to their parents cry for help.

Six boys were rescued from being trafficked when buses were stopped by police

The government has taken steps to stop trafficking, including passing a more stringent law, and asking states to strengthen and expand anti-human trafficking in the wake of the lockdown.

States have also been asked to spread awareness about trafficking, and keep shelters for women and children accessible even during the pandemic.

But, activists say, most traffickers get away with paying fines because they are connected to powerful people. Mr Kumar said families rarely report trafficking, and those that do register police complaints are threatened.

Mr Lal 's family got lucky - the bus carrying his son was stopped while on its way and the children inside were rescued. His son is now quarantining in a child care centre in Rajasthan and will return home soon.

"It was a moment of weakness," he said. "I will never send my child to work again even if it means we have to survive on morsels."

- Published11 April 2020