Hathras case: Are Indian state police trying to discount a woman's story of rape?

- Published

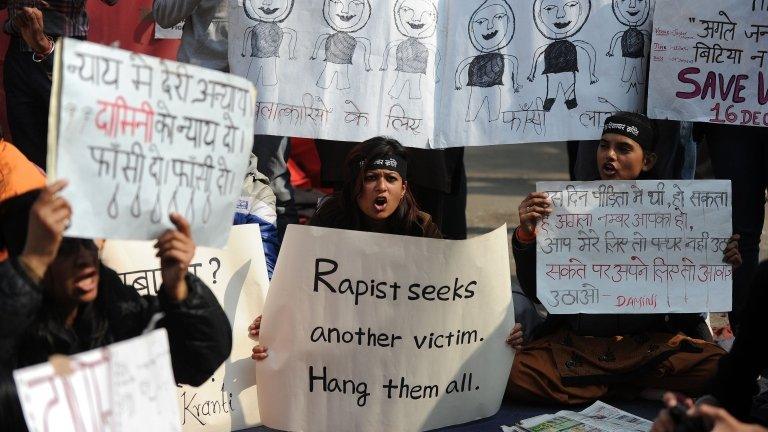

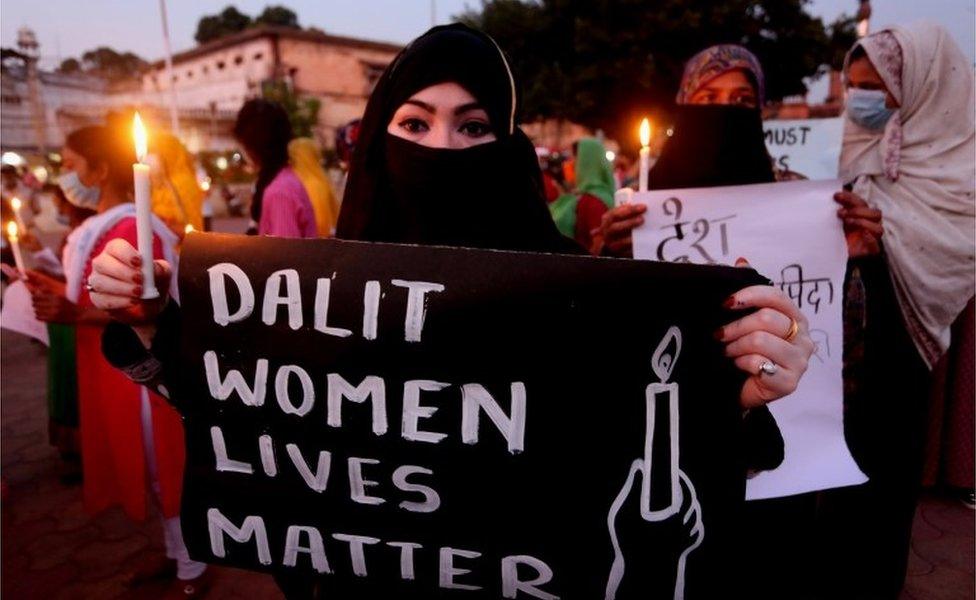

There have been countrywide protests against the rape of the 19-year-old

Days after the death of a 19-year-old Dalit woman who was allegedly gang raped and assaulted in India's northern Uttar Pradesh state, a senior state police official appeared to imply the woman was not raped because semen was not found.

Additional Director General Prashant Kumar told reporters on Thursday that the forensic report had found "no semen or semen excretion" in the viscera sample of the victim, and the cause of death was due to "trauma caused by the assault".

Mr Kumar also claimed that the woman's family had not mentioned rape in the initial complaint. But in fact the victim had given a statement to the police in the presence of a magistrate in the hospital saying that she had been gang-raped. A dying declaration by a rape victim is admissible evidence in India's courts.

And he said there had been attempts to stir caste tensions and disrupt peace by "putting out twisted facts in the media" - possibly an allusion to the widespread coverage that the teenager, a Dalit, had been gang-raped and murdered by upper-caste men. Dalits sit at the bottom of India's caste system and are some of the country's most downtrodden citizens. They face widespread discrimination, despite laws to protect them.

Taken together, Mr Kumar's remarks appeared to suggest that the teenager was not raped, and that the reported absence of semen in the viscera sample was significant evidence.

Except it was not.

Seven years have passed since India introduced an anti-rape law which expanded the definition of rape to include oral sex and penetration with objects. The law also says explicitly that the absence of a physical struggle doesn't equal consent.

"The law is extremely clear about the definition of rape," Gopal Hosur, a retired senior police official, told me. "Police officers should not jump to conclusions. The presence or absence of semen by itself does not prove rape. We need a lot of other circumstantial and other evidence," he said.

The victim's brother said that police have been trying to suppress the entire case

Legal experts believe that remarks like Mr Kumar's might be because some of India's policemen are possibly still not aware of the nuances of the new law, or are carelessly lazy when defining it.

"The majority of officers are aware of the new law. But I think unlearning of the old colonial law has been slow. Even after extensive training, a small percentage of policemen still don't understand the new law," Mrinal Satish, a doctorate from Yale Law School who has extensively researched rape sentencing in India, told me.

Others believe that policemen end up making misleading statements because of media or even pressure from the government.

"India now has a very aggressive and intrusive media and on a day-to-day basis police are forced to answer questions on specific matters," Prakash Singh, a former chief of police in Uttar Pradesh, where the latest incident took place, told me. "When an officer mechanically says no semen has been found in a forensic sample, it's a remark which is neither here nor there and leads to more problems."

Also, doctors question the reliability of the forensic sample taken from the rape victim. The incident happened on 14 September. Eight days later, she gave a statement to the police saying she had been gang raped. The forensic sample - including vaginal swabs - was sent to the forensic laboratory on 25 September, 11 days after the incident.

India's exhaustive 73-page guidelines and protocols for medical examination of victims of sexual violence clearly say that if a woman reports the incident within four days - or 96 hours - of assault, all evidence including swabs should be collected.

The woman's family has accused the police of cremating her body without their permission

The likelihood of finding evidence after three days - or 72 hours - is "greatly reduced", the guidelines say. They add that it is better to collect evidence up to 96 hours in "case the survivor may be unsure of the number of hours lapsed since the assault".

Also, the sperm - which is part of semen - can be identified only for 72 hours after the assault.

"So if a survivor has suffered the assault more than three days ago, please refrain from taking swabs for sperms," the guidelines say, adding that in such cases swabs should only be sent for identifying semen.

"The sample was not taken in time. What use does it have as any evidence now?" said Dr Hamza Malik, who works in the hospital in Aligarh city where the victim was admitted before being shifted to a hospital in Delhi.

Clearly, the latest case of sexual violence that has roiled India is already mired in allegations of tardy investigations, lax forensics and dubious statements by the police.

These factors, taken together, have raised suspicions of a cover-up. The fact that many Indians are still not informed enough about the rape laws doesn't help. "People are not educated about the law, and that adds to the confusion," said Dr Satish.

Delhi Nirbhaya rape death penalty: How the case galvanised India

- Published28 March 2013