The Tibetans serving in ‘secretive’ Indian force

- Published

Tenzin's family said he served in a covert military unit for decades

For decades, India has recruited Tibetan refugees to a covert unit dedicated to high-altitude combat. But the recent death of a soldier in the force has put the spotlight on this unit, reports the BBC's Aamir Peerzada.

A photograph of Nyima Tenzin was kept in the corner of his house, surrounded by warm light spilling from oil lamps. The hum of prayers continued in the next room, where family members, relatives and Buddhist monks were chanting.

Days earlier, the 51-year-old soldier had died in a landmine blast near Pangong Tso Lake in the Himalayan region of Ladakh, where Indian and Chinese troops have been facing off in recent months. Sources in the Indian army told the BBC that he was killed by an old mine left from the 1962 war the two countries fought.

"On 30 August, around 10:30 in the night, I got a call, saying he was injured," Tenzin's brother, Namdakh, recalled. "They did not tell me that he had died. A friend confirmed the news to me later."

Tenzin's sister lights lamps at their home in Leh

Tenzin, his family told the BBC, had been a member of the Special Frontier Force (SFF), a covert military unit largely comprising Tibetan refugees, external. It reportedly has about 3,500 soldiers.

Tenzin was a refugee too and he had served in the force for more than 30 years, his family said.

Little is known about the SFF, whose existence has never been officially acknowledged by Indian officials. But it's also a well-known secret, familiar to military and foreign policy experts as well as journalists who cover the region.

Yet, Tenzin's death - in the last weekend of August amid rising tensions between India and China - prompted the first public acknowledgement of Tibetans' role in the Indian military.

The people of Leh, the capital of Ladakh where Tenzin lived, and the Tibetan community came together to bid him farewell, external in a grand funeral, complete with military honours, including a 21-gun salute.

Nyima Tenzin waas given a grand funeral with full military honours

Senior BJP leader Ram Madhav attended the funeral and placed a wreath on Tenzin's coffin, which was draped in the flags of India and Tibet and was carried to his home in an army truck.

Mr Madhav even tweeted, external, describing Tenzin as a member of the SFF and "a Tibetan who laid down his life protecting" India's borders in Ladakh. He later deleted the tweet in which he also referred to an Indo-Tibet border rather than an Indo-China border.

Although the government and the army made no official statement, the funeral was widely reported in national media, which interpreted it as a "sharp signal", external and a "strong message", external to Beijing.

"Till now this [the SFF] was a secret, but it has been acknowledged now and I am very happy," said Namdakh Tenzin. "Anyone who serves should be named and supported.

"We fought in 1971, which was kept a secret, then in 1999 we fought Pakistan in Kargil, that was also kept a secret. But now for the first time it has been acknowledged. This makes me so happy."

The SFF, experts say, was created after the 1962 war between India and China.

"The aim was to recruit Tibetans who had fled to India, and had high altitude guerrilla warfare experience, or were part of Chushi Gandruk, a guerrilla Tibetan force, which fought China till the early 1960s," said Kalsang Rinchen, a Tibetan journalist and filmmaker, whose documentary Phantoms of Chittagong is based on extensive interviews with former SFF troops.

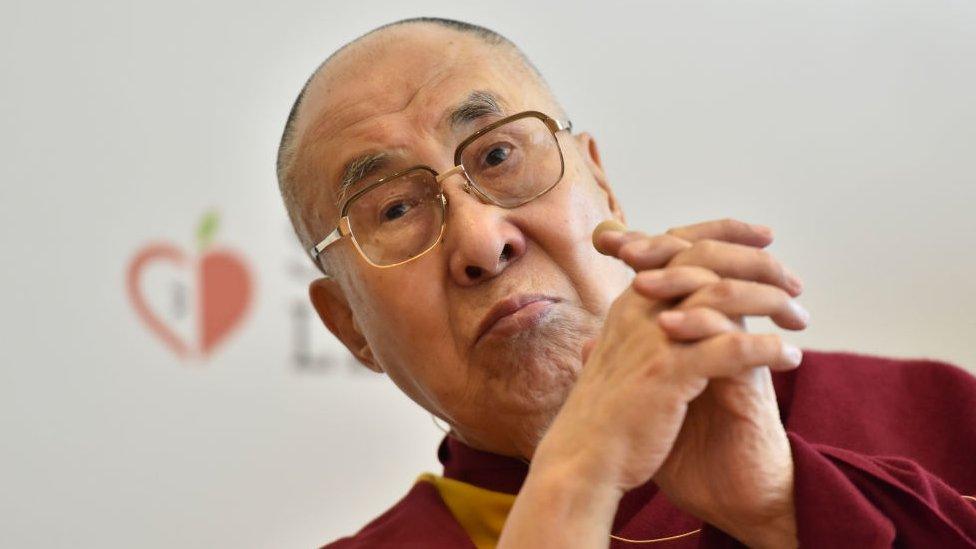

In 1959, after a failed anti-Chinese uprising, the 14th Dalai Lama fled Tibet and set up a government in exile in India, where he continues to live. Tens of thousands of Tibetans followed him into exile and sought asylum in India.

Local Tibetans and Tenzin's family attended his funeral

India's support f the Dalai Lama, and the refugees who came with him, quickly became a source of friction between the two countries. India's humiliating defeat in 1962 added to the tension.

BN Mullik, the then chief of Indian intelligence, is reported to have set up the SFF, external with the help of the CIA. The extent of Washington's role is disputed - while some sources say it was a purely Indian initiative with "full endorsement" from the US, others say that some 12,000 Tibetans were trained by US special forces and partly funded by the US.

"Most of the training was given by Americans," Jampa, a Tibetan refugee, who joined the SFF in 1962, told the BBC.

"There was one guy from the CIA who spoke in broken Hindi - he trained four of our men who understood Hindi as most of us didn't know Hindi. Then those four men trained others."

The force only recruited Tibetans initially but later expanded to include non-Tibetans. Throughout, experts say, the force has reported directly to the federal cabinet and is always headed by a high-ranking official from the army, external.

"The primary motive was to fight China covertly and gather intelligence," Mr Rinchen said.

The Chinese deny any knowledge of the SFF.

"I'm not aware of Tibetans in exile in the Indian armed forces. You may ask the Indian side for this," Chinese spokesperson Hua Chunying said in a recent press conference.

Tenzin died in a mine blast near the Pangong Tso lake

"China's position is very clear. We firmly oppose any country providing convenience in any form for Tibet independence forces' separatist activities," she added.

Beijing still governs Tibet as an autonomous region of China. And its relations with India have worsened since June when border clashes between the two sides left 20 Indian soldiers dead. India said Chinese soldiers also died in the clash but Beijing has not commented on this.

The cause of the decades-long tension is the poorly demarcated border between the two countries - it cuts through miles of inhospitable terrain.

"It's an odd situation for India," says professor Dibyesh Anand, head of the School of Social Science at the University of Westminster. "India has essentially indicated to China that it will use Tibetans against them, but officially they will not say that."

"We did everything the Indian army does, but we never got the usual military honours or acknowledgement - it still makes me sad," Mr Jampa, the former SFF fighter, said.

It's hard to say what impact India's recent subtle acknowledgement of the SFF will have on its relations with China. But the tensions between the neighbours certainly worry more than 90,000 Tibetans in India, many of whom still hope to return to Tibet some day.

But India feels like home too.

"We all feel proud that Tenzin gave his life for two of our countries - India and Tibet," said his brother-in-law, Tudup Tashi.

You may also be interested in:

India formally divides Jammu and Kashmir state

- Published2 December 2017

- Published27 June 2019