India farmer protests: Have rural incomes struggled to keep up?

- Published

There's been mounting anger over the new farming laws

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi has announced the repeal of three agricultural laws that had led to year-long protests by farmers.

However, farmers say they will continue to protest until other demands are met, including guaranteed minimum prices for their produce and increased wages.

Leaders from the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) said the new farms laws would double farmers' income - a promise originally made by Mr Modi in 2016.

So is there any sign of rural livelihoods improving?

What's happened to rural incomes?

Around 40% of India's workforce is engaged in agriculture, according to the World Bank.

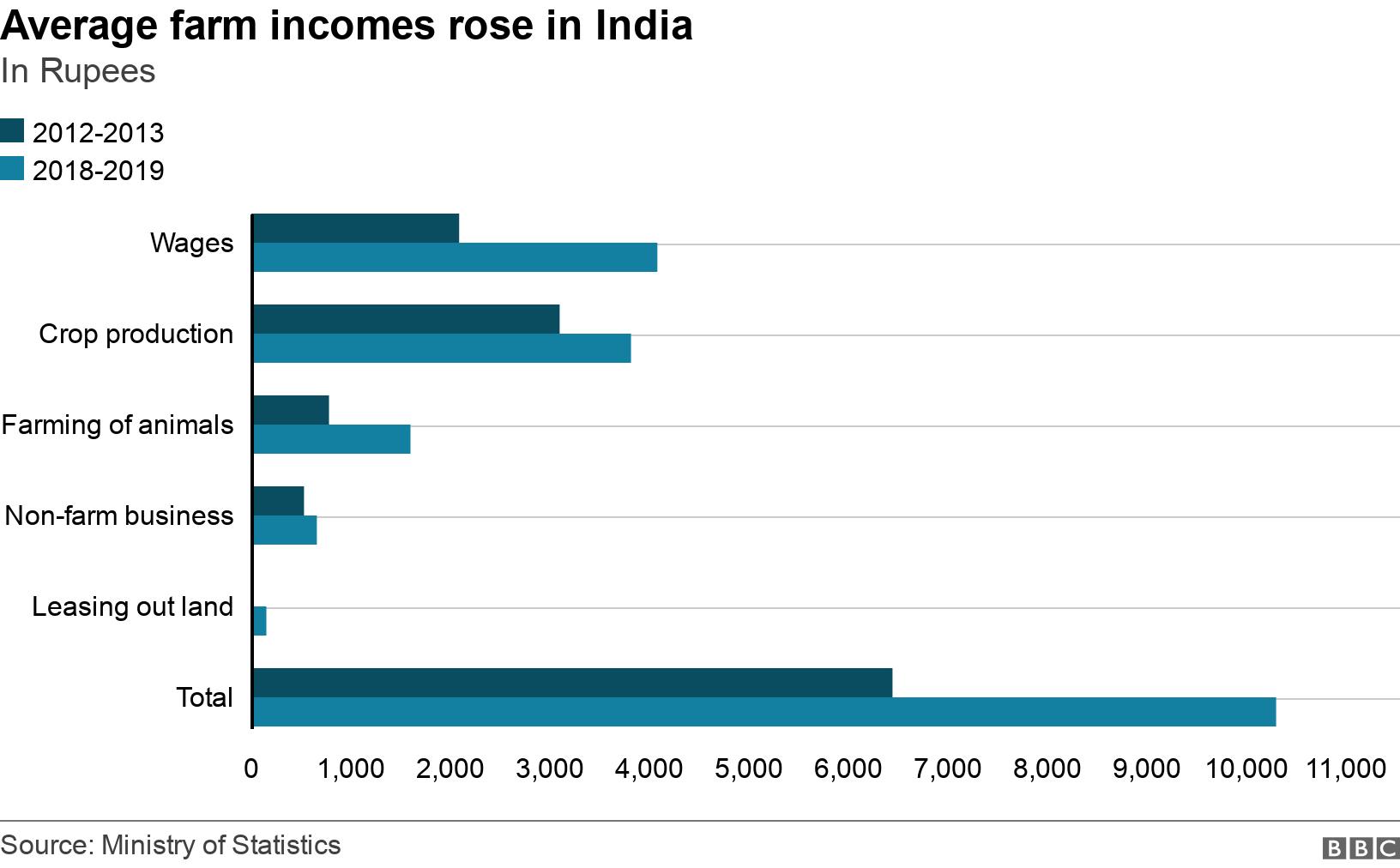

The average monthly income of agricultural households rose 59% in absolute terms between 2012 and 2019, according to official data.

However, it's worth noting that the most recent data for that period includes an additional source of income not factored in to earlier estimates.

Also, rising inflation has eaten into real wages. After adjusting for inflation, incomes grew only by 16% in real terms over that period.

In 2018, a report by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), external estimated that farmers' incomes increased by just 2% a year in real terms between 2013 and 2016.

The report also made clear that these farmers' incomes were just one-third of those for non-agricultural households.

Agricultural policy expert Devinder Sharma believes farmers' incomes in real terms have remained stagnant or even declined for several decades.

"An increase of a couple of thousand [rupees] a month doesn't make much difference if we account for inflation," he says.

He also points to the rising costs that farmers face, as well as the wildly fluctuating prices they receive for their produce.

More than 40% of India's workforce is in the rural economy

It's also worth adding that in recent years, there have been periods of extreme weather such as droughts, which have seriously affected rural livelihoods.

Are government targets being met?

In 2017, a government committee reported that incomes for farmers would need to grow by 10.4% each year from 2015 for them to double by 2022.

That's not been happening.

It also said the government needed to invest 6.39bn rupees (£64bn; $86bn) in the agricultural sector.

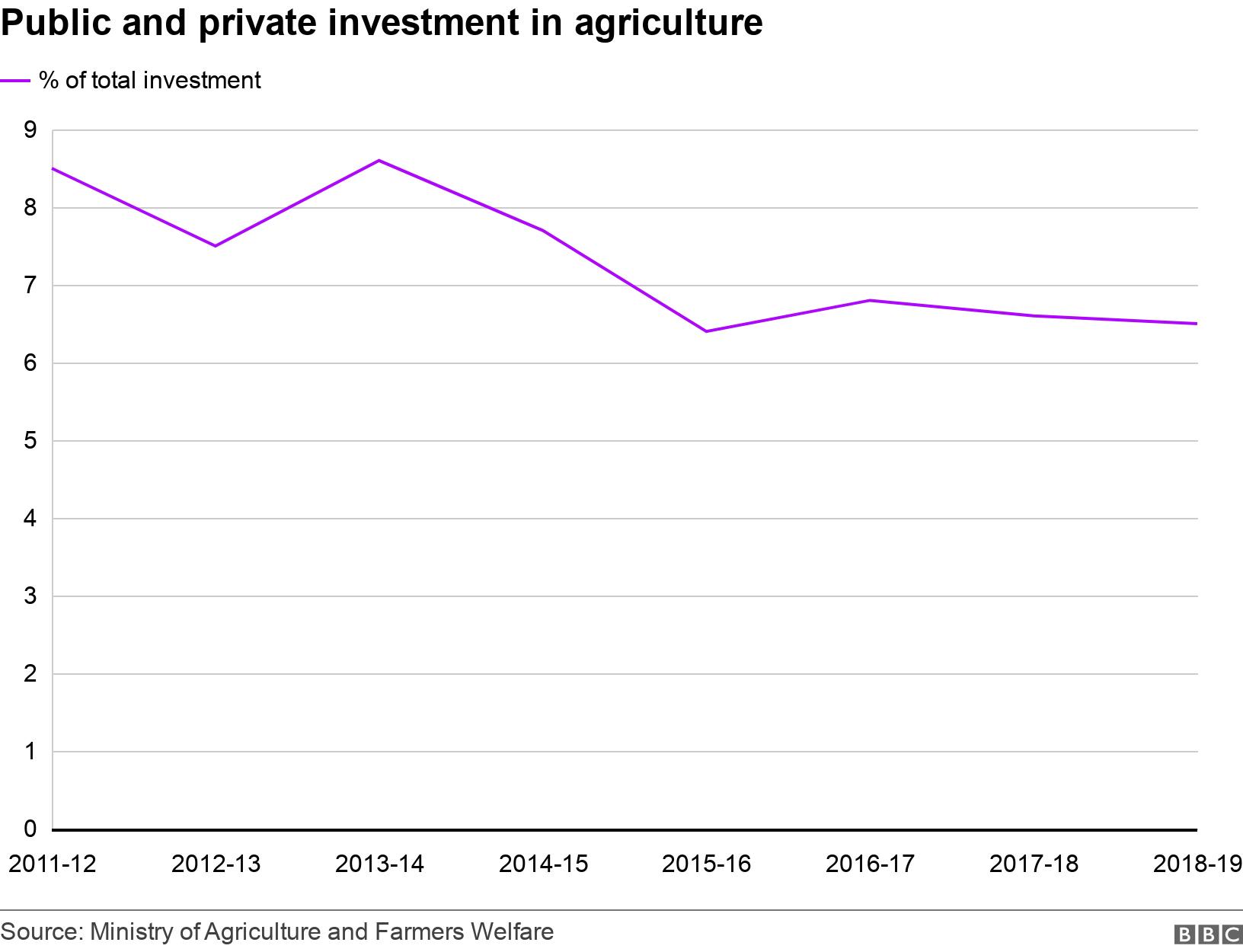

Data on both public and private investment shows it has been falling for most of the period between 2013 and 2019.

In 2011-12, investment in agriculture as a percentage of total investment stood at 8.5%.

It rose to 8.6% in 2013-14 and then fell, staying more or less flat at between 6% and 7% after 2015.

Farmers sinking into debt

While incomes showed a slight increase, the average figure for outstanding loans in farming households rose by 59% between 2012 and 2019.

Reality Check has previously looked at the plight of farmers facing high levels of debt and the political debate over whether they should receive debt relief.

However, it is worth noting that experts believe that not all debt is bad and it can indicate that rural credit schemes to enable famers to buy equipment and other things are working.

There have been attempts at federal and state level over the years to give farmers direct financial and other support, such as subsidies for fertilisers and seeds.

In 2019, the federal government announced a direct cash transfer scheme targeting 80 million farmers.

Under the scheme, the government provides income support of 6,000 Rupees (£61; $81) per year.

Chrysanthemum flowers are an important crop in southern Karnataka state

Six states in India already had their own state-run cash transfer schemes for farmers prior to that.

Devinder Sharma says such schemes have helped raise farmers' incomes.

"The government brought in direct income support to farmers and it was a good step in the right direction."

But we don't yet have the data to show if these schemes have worked or not.

Ashok Dalwai, chairman of an official committee looking into increasing farmers' incomes, says he believes the government is on the right track.

"We should wait for the data," he says. "But I can say that the last three years would have accelerated the growth, [and] we will have more robust growth thereafter."

Mr Dalwai told the BBC that their own "internal assessment" showed that things were going "in the right direction."

This story was originally published in February 2021 and has been updated to reflect recent announcements and data.