Farmer protests: India's sedition law used to muffle dissent

- Published

Disha Ravi is an environmental activist and campaigner

A controversial colonial-era law has come under the spotlight in India with the recent arrest of a young climate activist.

Disha Ravi, who has now been released on bail, was charged under the statute which critics say is being increasingly used by the government to silence its opponents.

What's the sedition law?

This is a section of the Indian Penal Code which criminalises any action that "excites or attempts to excite disaffection towards the government".

The punishment can be a fine or a maximum sentence of life in prison, or both.

Protests were held in Delhi after a activist Disha Ravi was charged with sedition

The law has been invoked for the liking or sharing of a social media post, drawing a cartoon or even the staging of a school play.

It dates back to the 1870s, when India was under British rule.

Saudi Arabia, Malaysia, Iran, Uzbekistan, Sudan, Senegal and Turkey also have legislation against sedition.

A form of sedition law also exists in the United States, but freedoms of speech enshrined in the US Constitution mean that it's rarely invoked.

The United Kingdom abolished sedition and seditious libel in 2009 after a protracted legal campaign against such laws.

Rise in sedition charges in India

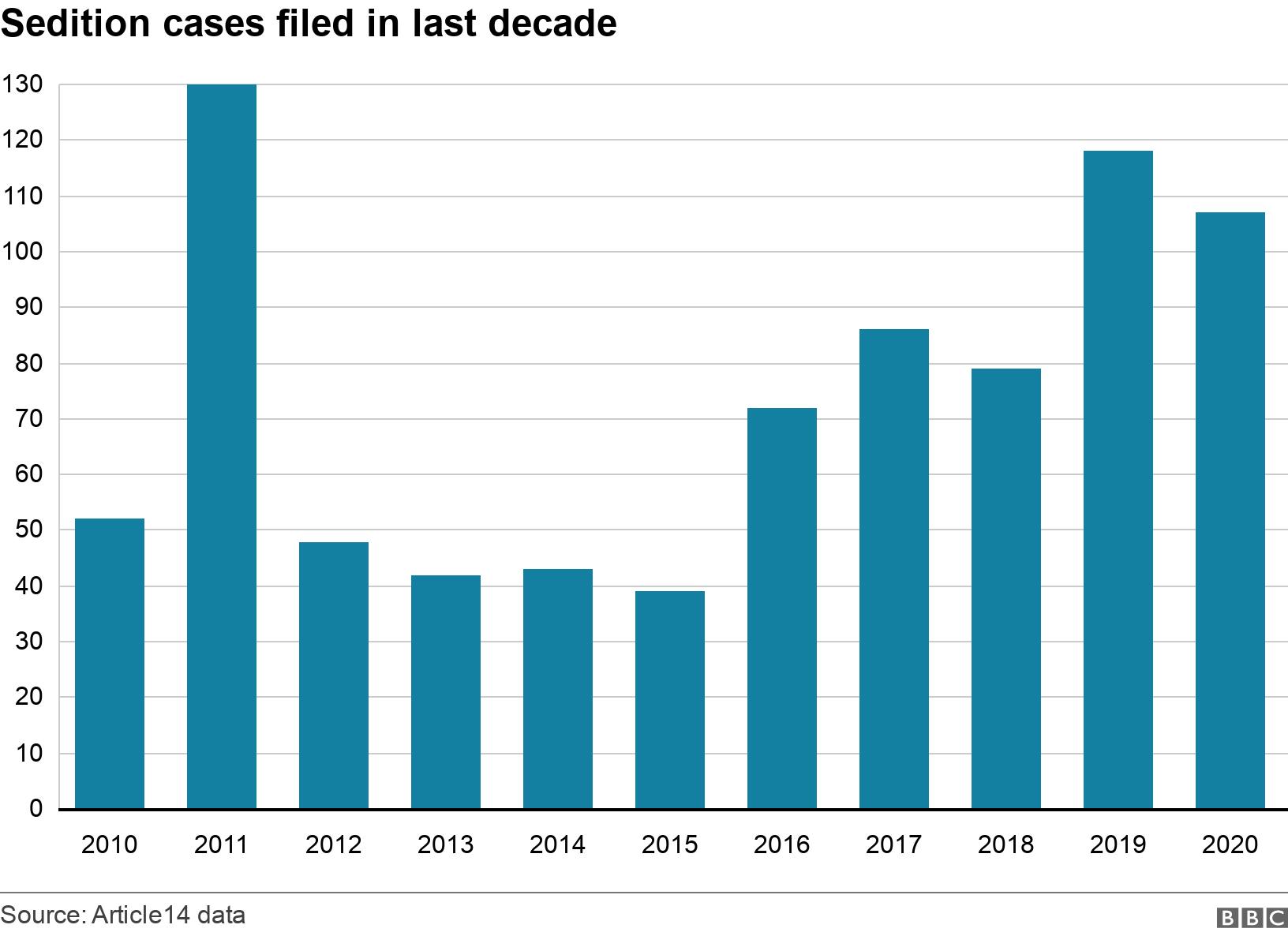

In the last five years, the number of sedition cases filed against individuals has risen by an average of at least 28% each year, according to data collected by Article14, a group of lawyers, journalists and academics, external.

India's official National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) didn't begin reporting sedition cases as a separate category until 2014.

And the number of cases reported by them is lower than those reported by Article14 because not every instance of sedition is recorded as such.

Lubhyathi Rangarajan, who oversees the database at Article14, says the group looks in detail at court documents and police reports to check exactly what charges were made.

"The NCRB works on the principal offence method, which means if there is a crime [involving sedition] which also includes either rape or murder, then the case will be classified under that offence."

A protest in Delhi last year after the gang rape of a Dalit woman in Uttar Pradesh

But both data sets show upward trends.

The Article14 database found that five states - Bihar, Karnataka, Jharkhand, Uttar Pradesh and Tamil Nadu - accounted for nearly two-thirds of all sedition cases in the last decade.

These are cases lodged by both the central and state governments.

Some are states affected by India's long-running internal conflict with Maoist guerrillas.

But the data also shows that the increase in recent years is linked to civilian protest movements, such as the current farmers' protests, as well as protests last year over changes to citizenship laws and over the gang rape of a Dalit woman in Uttar Pradesh.

Why is sedition being used?

There have been legal rulings and observations made by the Indian courts questioning the use of sedition laws.

The Delhi court that granted bail to Disha Ravi said the sedition law cannot be invoked to "minister to wounded vanity of the government".

India's top court has also stated that charges of sedition cannot be made unless the accused incites people to violence against the government, or with the intention of creating public disorder.

Official data shows that the conviction rate for sedition has actually dropped, from 33% of cases in 2014 to 3% in 2019.

Senior lawyer Colin Gonsalves, who has challenged the validity of the sedition law, says it is being used as an intimidation tactic.

"The state is terrorising young people by using the law and putting them behind bars."

Mr Gonsalves says the process itself is the punishment, rather than a trial or a conviction.

Tom Vadakkan, national spokesperson of the ruling BJP, defends the use of the law.

"We are a country that believes in non-violence but if there are elements that provoke and create conditions that affect the image of this country, this law is still relevant," he says.

As for the low conviction rate, he says: "In many of these cases, there's not enough evidence. Sometimes it's difficult to get to the bottom of it."

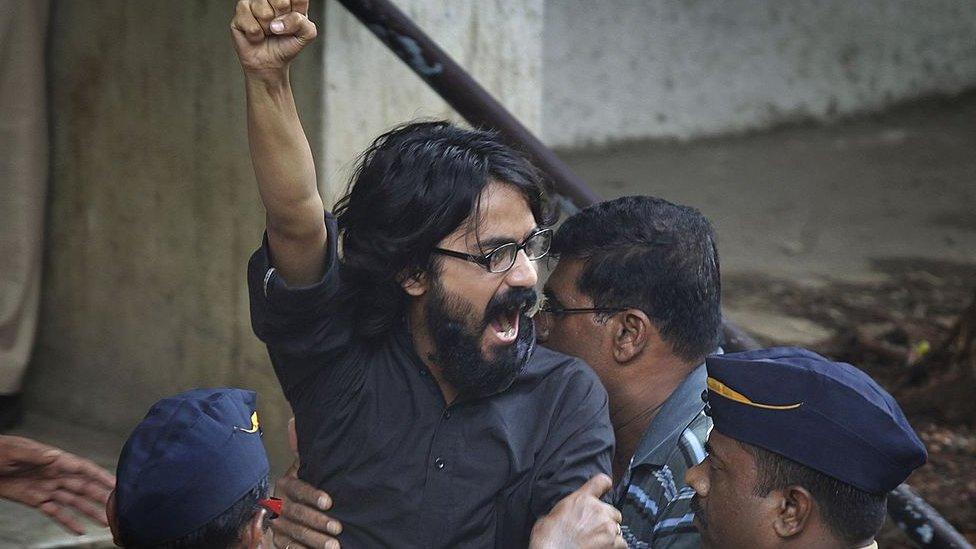

Cartoonist Aseem Trivedi was charged with sedition under the previous Congress-led government

Cartoonist Aseem Trivedi - arrested for sedition by a Congress-led government in 2011 and then freed after protests - says things look different today.

"I just got lucky," he says. "If I hadn't received widespread support, I would have had to spend the rest of my life fighting the case and spending all my money on it.

"I am certain that [today] the charges would not have been dropped, I would have had to fight inside and outside the courts to defend myself."

Related topics

- Published29 August 2016

- Published6 September 2016