Covid-19: Has India's deadly second wave peaked?

- Published

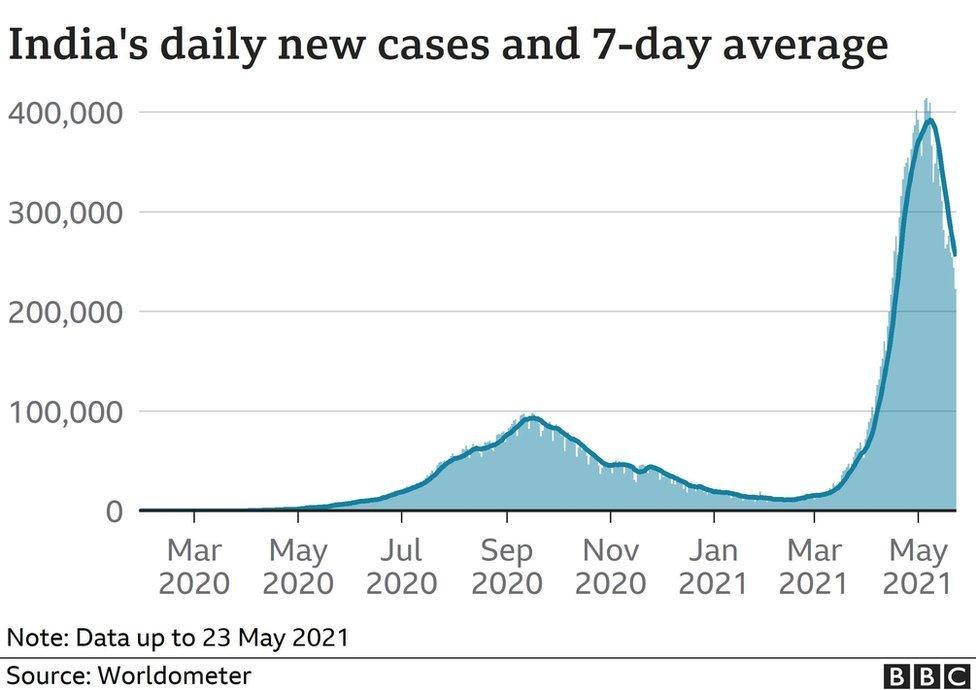

On Monday, cases fell below 200,000 for the first time since 14 April

India has recorded 26 million Covid-19 cases - second only to the US. It is the new epicentre of the global pandemic.

The second wave in recent weeks has overwhelmed the healthcare system, leaving hospitals struggling to cope and critical drugs and oxygen in short supply.

But infections now seem to be slowing down. On Monday, cases fell below 200,000 for the first time since 14 April.

So is the second wave coming to an end?

Experts believe that at a national level, the wave is waning.

The seven-day rolling average of new reported cases during the wave peaked at 392,000 and has been on a steady decline ever since for the past two weeks, according to Dr Rijo M John, a health economist.

But there's a catch.

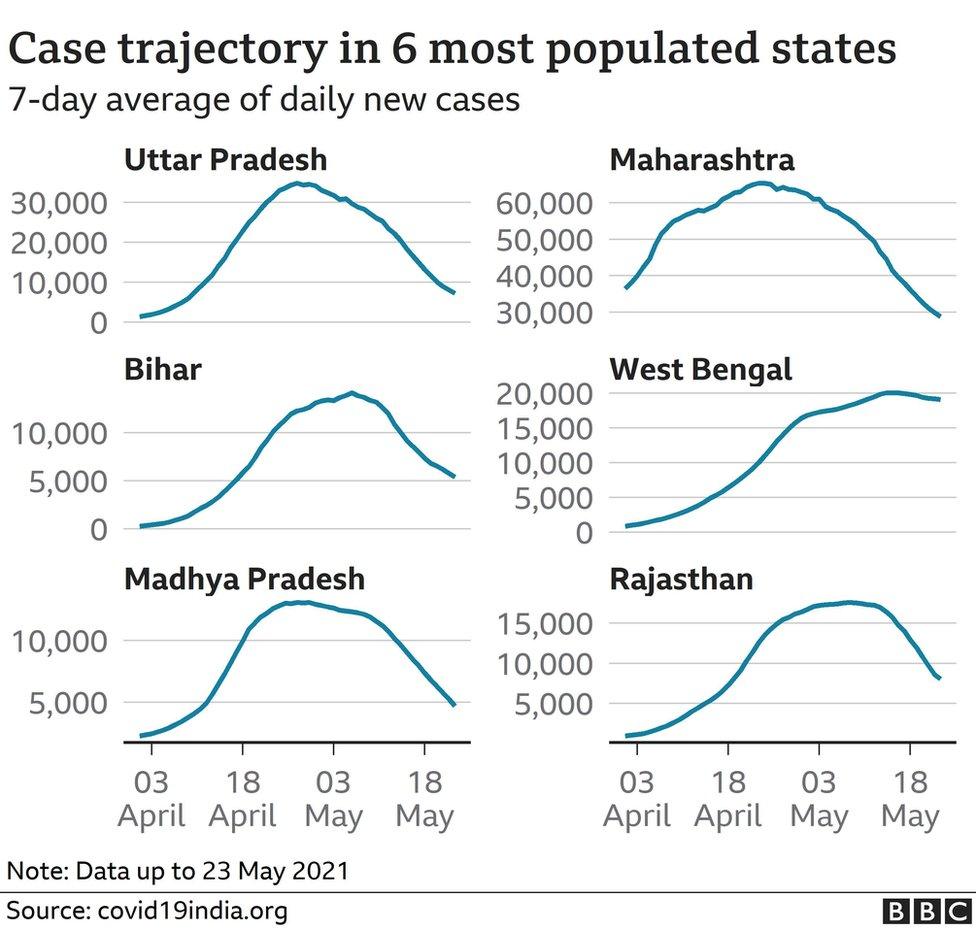

Even if the second wave appears to be waning for India as a whole, it is by no means true for all states.

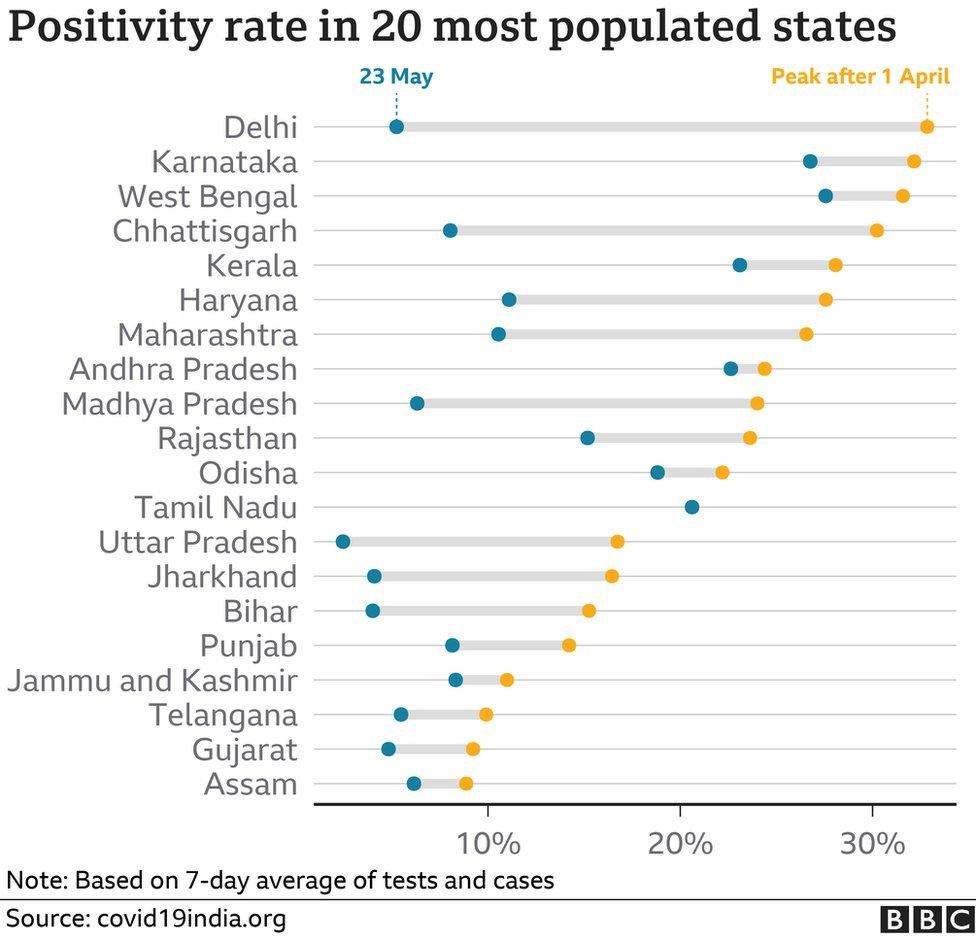

It appears to have crested in states such as Maharashtra, Delhi and Chhattisgarh, but is still rising in Tamil Nadu, for example, as in much of the north east; and the situation in Andhra Pradesh and West Bengal is unclear.

So the wave is not uniform and there are several states that are yet to find their peak in daily new cases, according to Dr John.

To be sure, infections are coming down in most of the major cities.

"But the weak rural surveillance complicates the picture," said Dr Murad Banaji, a mathematician at Middlesex University London. "It is possible that total transmission nationwide has not peaked yet, but this is not visible in case numbers because the infection is mostly spreading now in rural areas," he said.

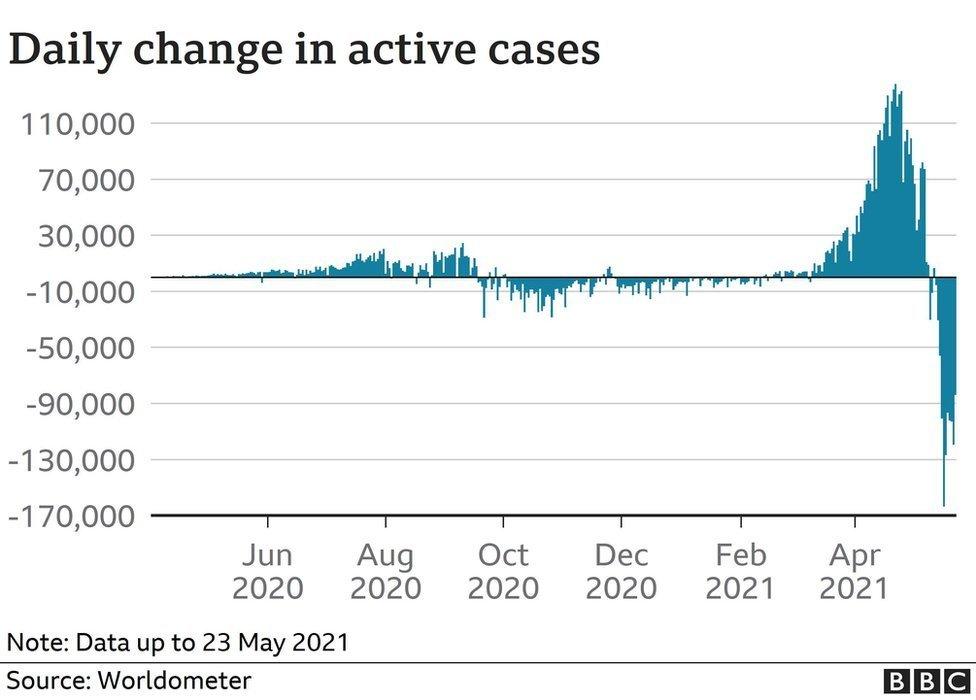

Such heterogeneity at the local level makes it very difficult to guess whether the India-wide trend of a sharp decline in active cases now is sustainable or not, according to Dr Sitabhra Sinha, a scientist at the Institute of Mathematical Sciences in Chennai.

Bhramar Mukherjee, a University of Michigan biostatistician who has been closely tracking the pandemic, agreed.

"The notion that the peak has passed may give false sense of security to everyone when their states are in fact entering the crisis mode," she said. "We must make it clear that no state is safe yet."

Does the virus's reproduction number offer any clues?

The reproduction number of the virus - also called R0 and R- is a way of rating a disease's ability to spread and estimates the average number of people infected by one already infected person.

The only difference between the two values is that R0 is calculated during the onset of the epidemic when almost the entire population is susceptible.

R, on the other hand, is calculated once the epidemic has progressed and a fraction of the population has already recovered and therefore is immune.

India's R number fell below 1 on 9 May, according to Dr Sinha.

"If this is a sustained trend and goes even lower in the subsequent weeks, then yes, we can expect to see a sharper fall in the number of cases," Dr Sinha said.

But the R for India "stayed close to 1 in the entire run-up to the second wave, so we need to be careful that this is not a fluke", he said.

"So it is quite possible that things can get worse if some state with a high R but a low number of active cases at the moment climbs up the charts as a result of the epidemic not being properly contained there."

When is the second wave likely to end?

The rate of decline of cases from the first wave was slow - active cases began declining only from late September last year, a trend which continued till the beginning of the second wave in the middle of February.

The decline appears to have been faster in the second wave, and it is not clear why.

Experts say one reason could be the virus has burnt through a large part of the population.

But then what about the fact that the second wave appears to have been driven by mutant strains to which previously infected people may not be entirely resistant?

Dr Mukherjee said her models indicated cases would come down to between 150,000 and 200,000 by end of May, and by the end of July may return to where they were in February.

But, she said, a lot would depend on how India's states exit from local lockdowns.

Positive rates should be at or below 5% for at least 14 days before a state or country can safely reopen, according to the World Health Organization.

Dr John says if India manages to test an average of 1.8 million samples daily, a positive rate of 5% would mean about 90,000 daily new cases.

"That will be a healthy sign that things are under control," he said.

What about the rising number of deaths?

India is only the third in the world to record more than 300,000 deaths - behind the US and Brazil.

The real number of fatalities might be much higher as many deaths are not officially recorded.

Dr Banaji said daily deaths had not yet obviously peaked because there's a time lag between cases peaking and deaths peaking.

But also, as with cases, there are huge variations in death surveillance and recording between states, and between urban and rural areas.

"Even when recorded fatalities start to fall, we'll need to be wary of reading too much into this until we stop hearing reports of large numbers of rural deaths," said Dr Banaji.

Dr Mukherjee said many more deaths were likely to happen in the month between mid-May and June - the models estimate 100,000 deaths during the period.

How does India's second wave compare with other countries?

The second waves in both the UK and US saw sharp rises and falls - and both peaked in early January.

However, a comparison with the decline of the second wave in other countries may be problematic, according to Dr Sinha.

He says most of Europe had the second wave around November-January which is the usual flu season.

A man sits next to his wife, suffering from fever, in a village in India

Even in normal years, a large number of people suffer from respiratory problems during this time - so a "spike wasn't entirely unexpected".

And the decline from the second wave has occurred at different rates in different countries.

In Germany, the decline from the peak of the second wave was, in fact, slower than the decline from the peak of the first wave, Dr Sinha said. In France, both declines occurred at about the same rate.

"I don't think that we can apply any universal rule gleaned from the rate of decline of the second wave to India - which escaped this particular flu season-associated wave," he added.

What happens next?

India will need more nuanced and strategic plans as it eases the second wave lockdowns.

Experts say opening indoor dining, pubs, coffee shops, gyms and similar "high risk facilities" should be delayed.

Gatherings should be allowed with less than 10 people outdoors or in highly ventilated areas. Big summer weddings in air-conditioned halls are a "virus pit", said Dr Mukherjee.

Experts say Indians should not let down their guard after the restrictions ease

Most importantly, the flagging vaccination drive needs to pick up speed, and mobile and mass vaccination drives should be introduced.

Also, experts say, India will need to closely track new variants or upticks in infection, using real-time epidemiological and sequencing data.

The country should also look at pool testing (combining samples for testing to save time and supplies) and wastewater testing (collecting wastewater and analysing for the virus).

Dr Banaji said it would be wrong to assume that the virus is running out of fuel.

"Immunity is not all or nothing: people infected earlier by an earlier variant of the virus may be vulnerable to re-infection and even transmit the disease."

India has so far partially vaccinated only 10% of its people.

"I don't think we should consider going back to normalcy at least until we are able to vaccinate 80% of our population," said Dr John.

Until then, maintaining Covid appropriate behaviour - mask, social distancing, sanitisation, avoidance of mass gatherings - would help check infections.

"Early declaration of victory over Covid-19 has already had disastrous consequences - we don't want to repeat that," said Dr Sinha.

Charts by Vijdan Mohammad Kawoosa/BBC Monitoring

Scenes outside a hospital in Delhi, where people are dying without getting the treatment they need

Related topics

- Published15 April 2021

- Published19 May 2021

- Published11 May 2021

- Published1 April 2021