Banished for bleeding: Tribal Indian women get better period huts

- Published

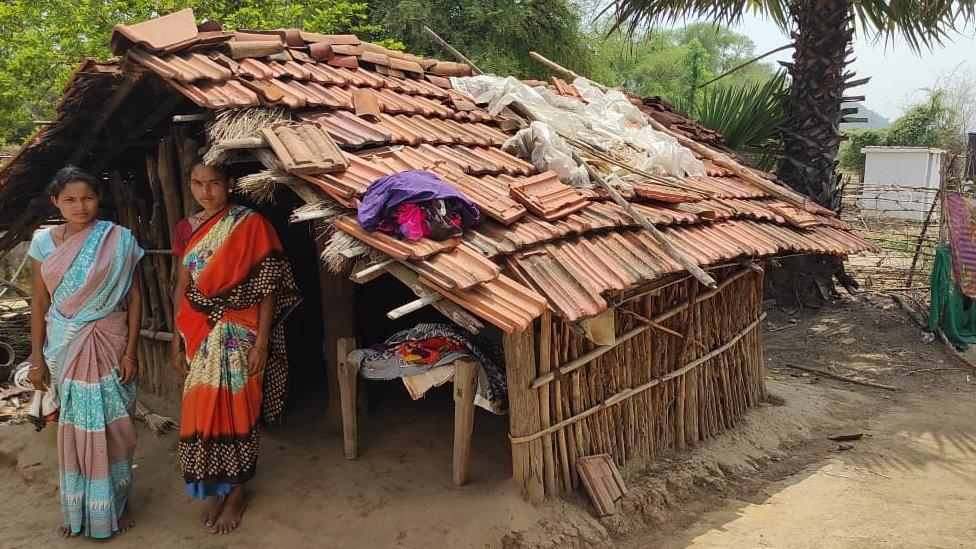

The women of Kanal Tola village are forced to live in this hut which has no door and no amenities

The "period huts" where thousands of tribal women and girls are banished during their menstruation in the western Indian state of Maharashtra are getting a makeover.

A Mumbai-based charity, Kherwadi Social Welfare Association, is replacing the mostly-dilapidated huts - known as kurma ghar or gaokor - with modern resting homes that have beds, indoor toilets, running water and solar panels for electricity.

But the drive has put the spotlight on the need to fight the stigma associated with what is a natural bodily function. Critics say a better strategy would be to get rid of these period huts altogether. But campaigners say they offer women a safe place to go, even if the period-shaming continues.

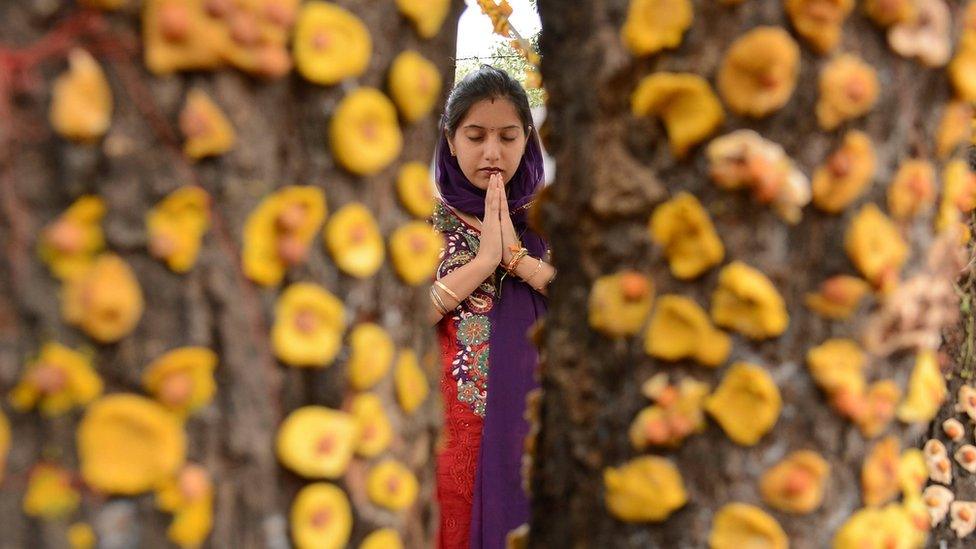

In India, periods have long been a taboo, with menstruating women considered impure and forced to live under severe restrictions. They are barred from social and religious functions and denied entry into temples, shrines and even kitchens.

But the exclusion the women of Gond and Madia tribes in Gadchiroli, one of India's poorest and most underdeveloped districts, face is extreme.

Their traditional beliefs mean they have to spend five days every month in a hut, located mostly on the outskirts of the village on the edge of the forest. They are not allowed to cook or draw water from the village well and have to depend on food and water delivered by female relatives. If a man touches them, he has to immediately bathe because he too becomes "impure by association".

The women of Tukum village - where the first modern period hut was built last year - say for the 90 menstruating females in their village, life is a lot easier now.

Earlier, they say, as their date would approach, the thought of going to the crumbling hut would fill them with dread. The mud and bamboo structure with a thatched roof had no door or windows and lacked even the most basic facilities. For bathing or washing clothes, they had to walk to a river one km away.

The women of Tukum say the new period hut has made their lives easier

Surekha Halami, 35, says during the summer, it was unbearably hot and infested with mosquitoes; in the winters, it would be freezing cold; and during the rains, the roof would leak and puddles would form on the floor. Sometimes, stray dogs and pigs would also come in.

Sheetal Narote, 21, says when she had to stay alone in the hut, she couldn't sleep at night from fear. "It was dark inside and outside and I wanted to go home but I had no choice."

Her neighbour, 45-year-old Durpata Usendi, says 10 years back, a 21-year-old woman staying in the hut died from a snake bite.

"We were woken up just after midnight when she ran out of the hut, crying and screaming. Her female relatives tried to help her, they gave her some herbs and local medicines.

"The men, even those from her family, watched from a distance. They couldn't touch her because menstruating women are impure. As the poison spread through her body, she lay on the ground writhing in pain and died a few hours later."

On a video call, the women give me a tour of their new hut - made from recycled plastic water bottles filled with sand, it's painted a cheerful red with hundreds of blue and yellow bottle caps embedded in the walls. It has eight beds and "most importantly" - the women point out - indoor toilets and a door they can lock.

Sheetal Narote says earlier if she had to stay alone in the hut, she couldn't sleep at night from fear

Nicola Monterio of KSWA says it cost 650,000 rupees ($8,900; £6,285) and took two-and-a-half months to build. The NGO has built four period huts and six more are due to open in mid-June in neighbouring villages.

Dilip Barsagade, president of Sparsh, a local charity that has been working in the area for the past 15 years, says a few years back, he visited 223 period huts and found that 98% were "unsanitary and unsafe".

From anecdotes the villagers provided, he collated a list of "at least 21 women who died while staying in the kurma huts from totally avoidable reasons".

"One woman died from a snake bite, another was carried away by a bear, a third was running high fever," he says.

His report prompted India's National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) to instruct the state government to "eradicate the custom" as it constituted "a serious violation of women's human rights... their safety, hygiene and dignity" but years later, the tradition remains deeply entrenched.

All the women in Tukum - and neighbouring villages - I spoke to said they didn't want to go to the period hut, that the lack of facilities sometimes made them angry, but added that they felt powerless to change a practice steeped in centuries of tradition.

Surekha Halami said she feared that if they defied tradition, they would face the wrath of gods and invite illness and death in the family.

"My grandmother and mother went to kurma ghar, I go there every month, and one day I would send my daughter too," she told me.

Some period huts like this one in Chandala Toli village are crumbling

Chendu Usendi, a village elder, told the BBC that the tradition could not be changed because "it's been decreed by our gods".

He said defiance was punished and those who broke tradition had to provide a feast for the entire village with pork or mutton and alcohol or pay a monetary fine.

Religion and tradition are often cited as main reasons for justifying restrictions, but increasingly, urban, educated women have been challenging these regressive ideas.

Women's groups have gone to court demanding entry into Hindu temples and Muslim shrines and social media campaigns such as #HappyToBleed have been organised to de-stigmatise periods.

Village women help with the construction of the new period hut

"But this is a very backward area and the change here is always gradual. Experience shows that we can't fight this headlong," says Ms Monterio.

The new huts, she says, will provide women a safe space now while we pursue the future goal of eradicating the practice by educating the community.

And that is easier said than done, Mr Barsagade says.

"We know better huts are not the answer. Women need physical and emotional support during menstruation which is only available at home. But we have seen that resistance is not easy. We don't have a magic wand to change the situation."

The biggest problem so far, he says, is that even women don't understand that it's a violation of their rights.

"But now I see the attitudes are changing and many of the younger, educated women are beginning to question the custom. It will take time but we will see the change someday in future," he says.

Using comics to combat India's menstruation taboos

Read more from Geeta Pandey

Related topics

- Published16 February 2020

- Published5 July 2019

- Published23 November 2015

- Published25 February 2019

- Published18 February 2016