Khurshedben Naoroji: The singer who preached nonviolence to bandits

- Published

Khurshedben Naoroji (centre) at a function in Germany in 1924

In most countries, the life of an elite, sophisticated woman renouncing her career as a classical soprano to preach nonviolence to bandits and kidnappers would merit significant study and attention. Yet in India, the woman in question, Khurshedben Naoroji, is largely unknown. Historian Dinyar Patel recounts her forgotten story.

The writer Ramachandra Guha once described the world of Indian biography as "a bare cupboard". Curiously, most scholars of India eschew writing life stories. A new book, external, with contributions from many of Guha's students and colleagues, helps to populate these empty shelves with some remarkable characters.

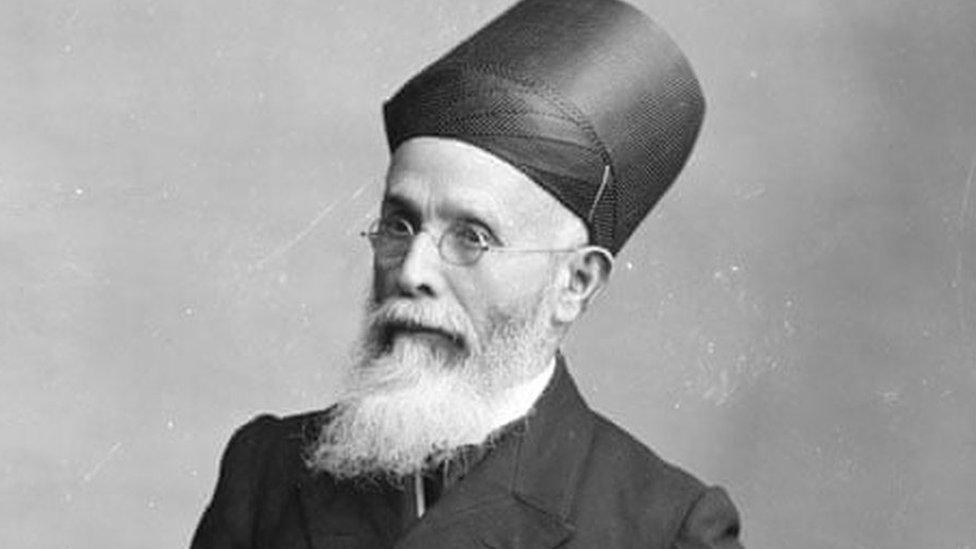

One of them is Khurshedben Naoroji, who was born in 1894 into an elite Parsi family. Her grandfather, Dadabhai Naoroji, was India's first nationalist leader and the first Indian to serve in the British Parliament.

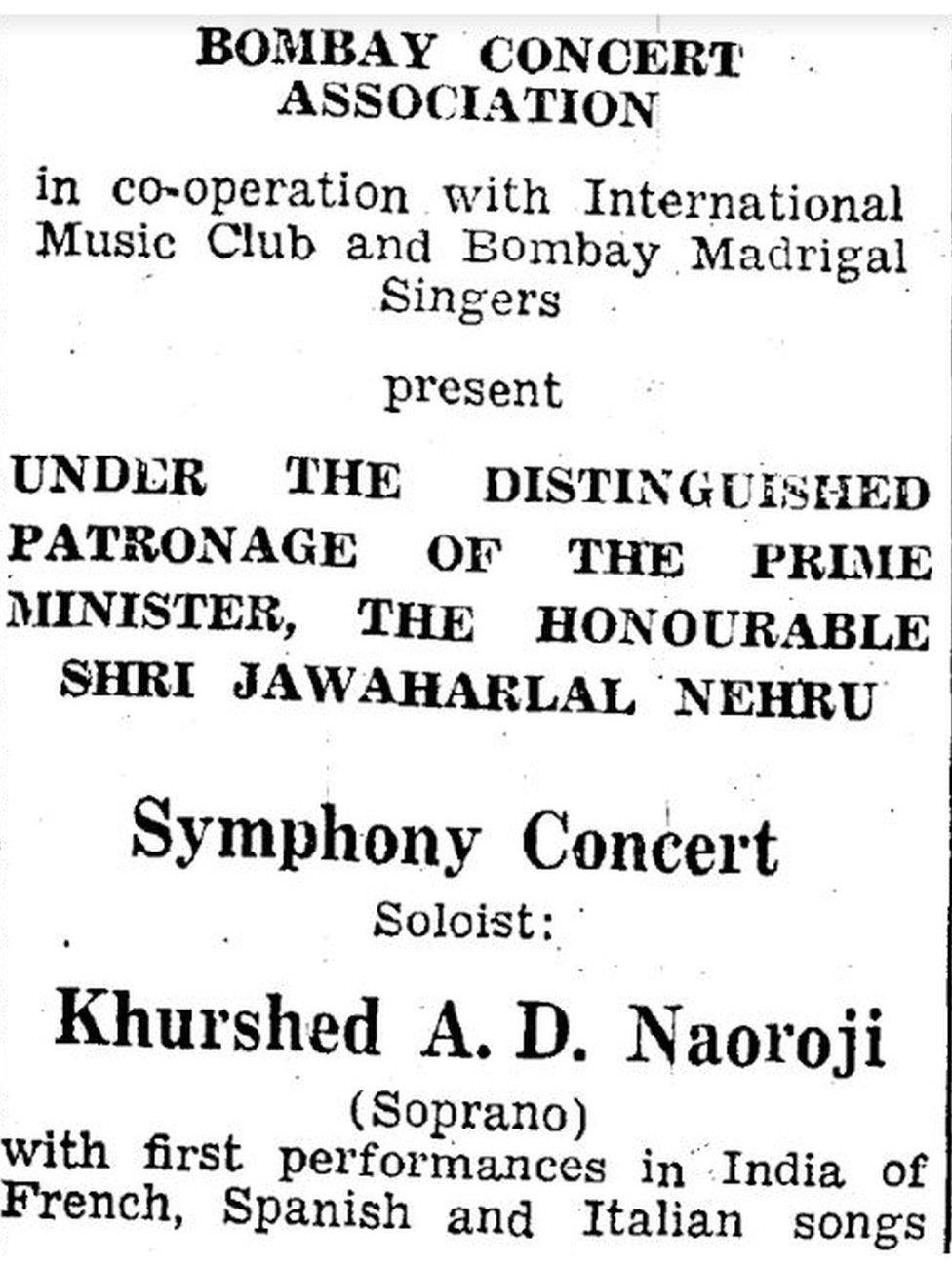

In her youth, Khurshedben lived in the poshest quarters of Bombay (now Mumbai) and became an accomplished classical soprano. Family and friends dubbed her "bul" or nightingale.

India's first PM Jawaharlal Nehru attended a concert by Khurshedben in Bombay (now Mumbai)

In the early 1920s, she relocated to Paris to study music, but found herself culturally adrift in Europe until she crossed paths with another expatriate woman, Eva Palmer Sikelianos.

Sikelianos, a New York aristocrat, had relocated to Athens where she became one of the principal architects of a revival of classical Greek culture.

Their conversations about Greek and Indian musical traditions resulted in the setting up of a school of non-Western music in Athens.

Khurshedben left classical music behind in Paris and flourished in Greece, donning Indian saris and holding impromptu Indian music concerts.

Remarkably, "Mother Greece" - as she referred to the country - helped refocus her energies on Mother India. As Sikelianos's biographer Artemis Leontis notes, Khurshedben spoke wistfully about India and about joining Mahatma Gandhi's movement for freedom from the British colonial rule. When Sikelianos solicited her help for the first Delphic Festival, external, Khurshedben turned down the offer, instead returning to Bombay.

Khurshedben, centre-left in a dark dress, at a function in Germany in 1924

Soon, she moved to Gandhi's Sabarmati ashram in Gujarat where she encouraged Gandhi to widen women's involvement in nationalist activities. Gandhian activism, she told a newspaper, allowed for "the great awakening of women" - and women were "not going to stop their work so well begun".

For Khurshedben, this work soon shifted to an unusual location: the North-West Frontier Province (NWFP - now in Pakistan and called Khyber Pakhtunkhwa). Deeply conservative and beset by tribal scrimmages and banditry, the region was about as distant from her Bombay as was possible. Perhaps that is what drew her to the place.

It's unclear how or when she first travelled to the Frontier, but by the early 1930s, this elite Parsi woman was a well-known figure in NWFP politics. She befriended Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan, the "Frontier Gandhi" who led a nonviolent pro-nationalist movement amongst Pashtuns.

Whenever she irked authorities, Khurshedben cheerfully submitted to imprisonment by the British, once writing to Gandhi from a prison in Peshawar (a city in today's Pakistan) that "the fleas and I kept each other warm".

As Khurshedben spent more time in the NWFP, she comprehended a thorny political challenge.

Gandhi had encouraged her to promote Hindu-Muslim unity and support for the Indian National Congress. This was impossible, however, while local Hindus remained terrorised by Muslim dacoits - bandits who conducted kidnapping raids from nearby Waziristan. These bandits, who terrified British and Indian policemen, stoked communal tensions.

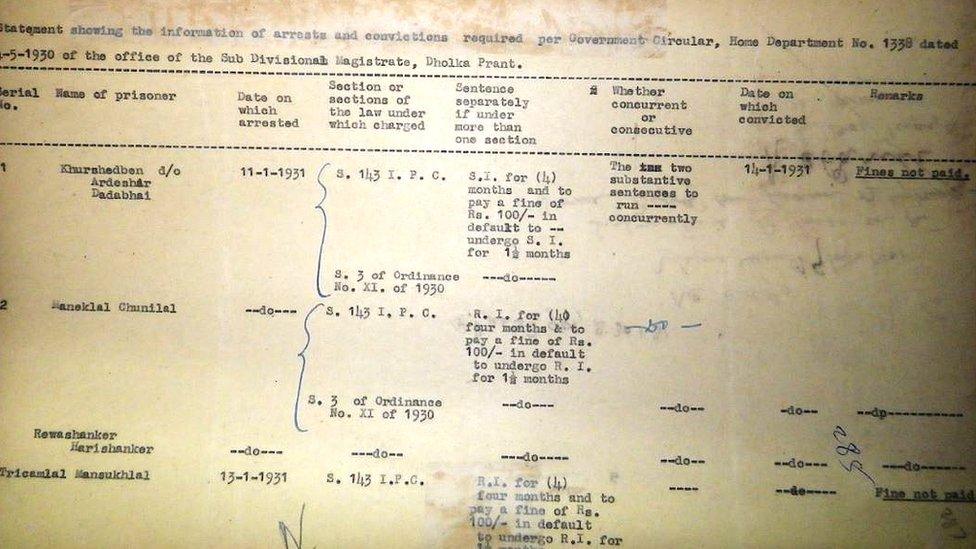

Khurshedben was arrested in 1931 on charges of unlawful political activity among other things

For Khurshedben, the answer to this dilemma was obvious - she would approach the dacoits, encourage them to desist from banditry and embrace Gandhian nonviolence.

Her Congress colleagues in the NWFP - all men - were mortified. Despite their protests, in late 1940 she began long tours on foot through the desolate countryside, meeting and conversing with locals. She counselled womenfolk about the evils of banditry, turning the mothers or daughters of dacoits against the practice.

Bandits were flummoxed about how to deal with this plucky woman who sallied right into their camps. Some expressed remorse about their activities but on at least one occasion, Khurshedben wrote to Gandhi about nearly being shot. "Bullets hissed in the sand near me," she recalled.

Remarkably, her approach yielded results. By December 1940, kidnappings had plummeted, improving communal harmony. Even local British authorities, her former incarcerators, now praised her.

But one challenge remained.

A group of kidnapped Hindus were being held in Waziristan, a place that British policemen dared not go. Khurshedben decided to go even though she was conscious of the risk to her life: and if she was captured alive, she told Gandhi that dacoits would ask him for a ransom or "chop off a finger or a(n) ear".

Unfortunately, she was unable to reach the kidnappers. British authorities arrested and jailed her before she crossed the Waziristan border. She cycled through prisons until 1944. Evidently, this elite woman from Bombay was too grave a danger for the British Raj.

Gandhi criticised the government's treatment of Khurshedben

Khurshedben never returned to the NWFP. In August 1947, she watched in agony as the region was wrenched away from undivided India; a few months later, Gandhi lay dead.

Information on Khurshedben's life almost completely disappears thereafter. Following Indian independence, she worked for various government commissions and even resumed her singing career before passing away, most likely in 1966.

In a sense, Khurshedben's story is hardly unique. Thousands of remarkable life stories like hers remain to be told, with scattered, moth-eaten archival records patiently waiting for a storyteller.

This is especially the case for women, including Khurshedben's female nationalist colleagues. There is plenty of space for them in the bare cupboard of Indian biographies.

Dinyar Patel is the author, most recently, of a biography of Dadabhai Naoroji: Pioneer of Indian Nationalism, which was published by Harvard University Press

- Published5 July 2020

- Published23 December 2020