Pegasus: Why unchecked snooping threatens India's democracy

- Published

More than 500 million Indians use smartphones

"You feel violated, there's no doubt about it," said Siddharth Varadarajan, co-founder of The Wire, a nonprofit news and opinion website in India.

"This is an incredible intrusion," he said. "Nobody should have to deal with this."

Mr Varadarajan, according to media reports, is one of the activists, journalists, politicians and lawyers around the world that have been targeted with phone spyware sold to governments by an Israeli firm. Of a leaked database of 50,000 numbers of interest to the firm's clients, more than 300 reportedly belong to Indians, according to The Wire, external.

The Wire was one of 16 international media outlets which investigated the leaked list and the use of Pegasus spyware.

This is not the first time Pegasus, which can infect smartphones without users' knowledge and access virtually all their data, and which is made by the Israeli software firm NSO Group, has been linked to the targeting of journalists and human rights activists.

In 2019, there was outrage in India and other countries after WhatsApp confirmed that some of its users were targeted with spyware. A total of 121 users, external from India, including activists, scholars and journalists, were affected by the breach. This, experts said, suggested the involvement of state agencies in India. (WhatsApp sued NSO, alleging the company was behind cyber-attacks on 1,400 mobile phones involving Pegasus.)

To be sure, it is still not clear where the new leaked list came from, who ordered the hack or how many phones had actually been hacked.

Now, as in 2019, NSO has denied any wrongdoing, saying the allegations had no "factual basis" and were "far from reality". A spokesperson for the firm told the BBC: "We will continue to investigate all credible claims of misuse and take appropriate action based on the results of these investigations".

Pegasus is a spyware made by an Israeli software firm, NSO Group

Similarly, India's Narendra Modi-led government has again denied accusations of any unauthorised surveillance.

Phones can be tapped in India "in the interest of sovereignty and integrity of India" and only on the orders from the senior-most official in charge of the home affairs ministry in the federal and state governments.

"But the processes of such authorisation have never been clear," Manoj Joshi, a fellow of the Delhi-based think tank Observer Research Foundation, said.

During a parliament debate on the breach in 2019, opposition MP KK Ragesh posed a number of pointed questions to the government: How did the Pegasus spyware come to India? Why were people "fighting against the government" targeted? How can one believe that the government has no role to play in bringing the software for snooping on political leaders in the country?" (NSO says it sells its technologies solely to law enforcement and intelligence agencies of "vetted governments" for the sole purpose of saving lives and preventing criminal and terror acts.)

Some 10 agencies in India are authorised to wiretap legally. The most powerful of them is the 134-year-old Intelligence Bureau, the country's largest and most powerful intelligence service with wide-ranging powers. Apart from surveillance on threats from terrorism, it conducts background checks on candidates for high office, like judges; and surveils, as one expert said, "political life and elections".

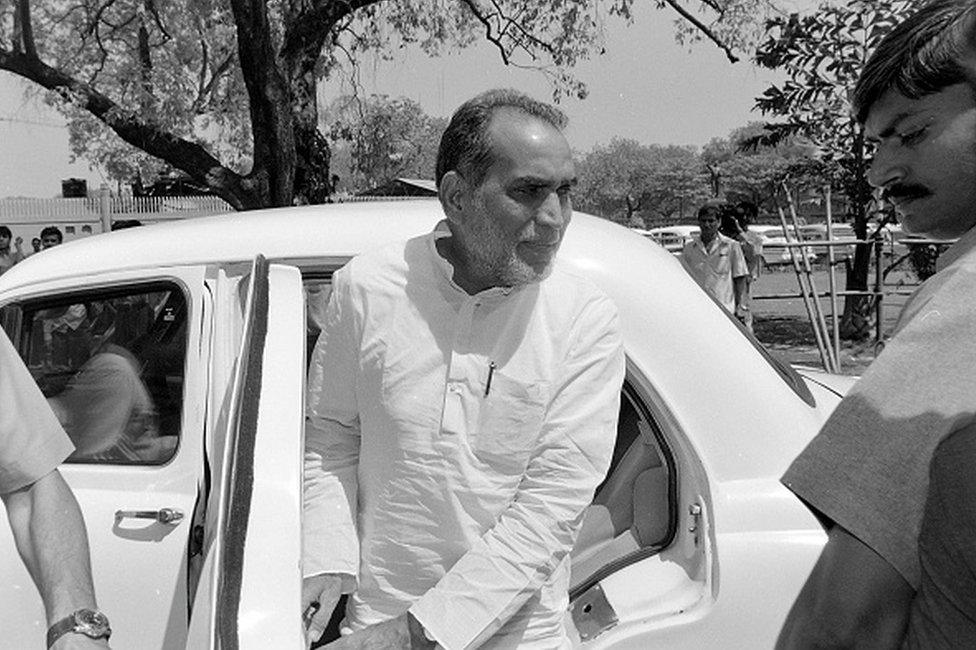

Former Prime Minister Chandra Shekhar once alleged that his phone was wire tapped

The intelligence agencies have a chequered history. Federal and state governments of all political hues appear to have used them to snoop on their opponents, and their own.

In 1988, the chief minister of Karnataka Ramakrishna Hedge quit after allegations that he ordered phone taps on at least 50 of his colleagues and rivals. In 1990, Chandra Shekhar, who later briefly became prime minister, alleged that the then government was illegally tapping phones of 27 politicians, including his own.

In 2010, 100 tapes of phone conversations between corporate lobbyist Niira Radia and leading politicians, industrialists and journalists recorded by tax investigators were leaked to the media. The then main opposition leader LK Advani remarked that the recordings reminded him of the Watergate scandal.

"What has now changed is the scale, speed and discreteness with which electronic surveillance is being done on those who dissent," Rohini Lakshane, technologist and public policy researcher, said.

Unlike the US, India has no special courts that authorise surveillance by state agencies.

Former federal minister and MP Manish Tewari has unsuccessfully tried to introduce a private member's bill in parliament to regulate the functioning and use of power by India's intelligence agencies. "There is no oversight of the agencies who are snooping on citizens. The time for such a law has come," Mr Tewari - who will reintroduce the bill in the ongoing session of the parliament - told me.

The latest episode, according to Ms Lakshane, points to the "scale and extent of electronic surveillance by the government and the lack of safeguards against such snooping". India, she said, was in "dire need of surveillance reform".

Parliament is likely to be roiled this week by this controversy. Ms Lakshane says it is a good time to ask some hard questions. What happens to intercepted data after it is used? Where is it stored and who exactly in the government has access to it? Does anyone outside government agencies have access to it? What are the digital security measures and safeguards?

What’s it like to have spyware on your phone?

Read more stories by Soutik Biswas