Indian women's hockey: Sixteen stories of struggle, one tale of triumph

- Published

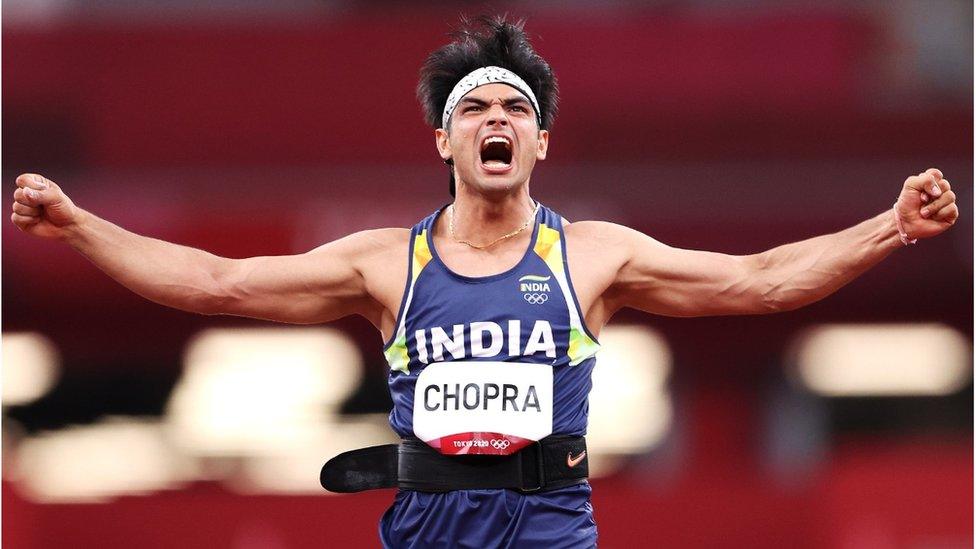

India defeated Australia 1-0 on Monday to make their maiden Olympic semi-final

The Indian women's hockey team made history by qualifying for their first Olympic semi-final - they lost to Great Britain in a nip and tuck battle on Friday. But the journey has not been an easy one, writes Deepti Patwardhan.

"What will she do playing hockey? She will run around the field wearing a short skirt and bring a bad name to your family," Rani Rampal's parents were told.

Vandana Katariya was discouraged to play hockey because it was "unbecoming of a girl". Neha Goyal, born to an alcoholic father prone to violence, sought solace in the hockey field.

Nisha Warsi's mother worked at a foam factory to keep food on the family's plate after her father suffered a paralytic attack in 2015. Nikki Pradhan, who hails from the tribal belt of Jharkhand, laboured in paddy fields and started playing hockey with borrowed, broken sticks on gravel playgrounds.

They tackled the odds, ignored the naysayers and silenced the critics. They overcame.

Rampal, Katariya, Goyal, Warsi and Pradhan are only some of the protagonists in India's history-making squad of 16.

For the first time, the women's hockey team competed for a medal at the Olympics. On Friday morning they played their hearts out before going down 3-4 to Rio 2016 gold medalists Great Britain in the fight for bronze.

Even before they left for the Olympics, not many gave them a chance to progress into the knockouts. But they did.

In the quarter-finals they took on former champions Australia. They played with the kind of skill that the world associates with Indian hockey, and the kind of pace no-one had quite expected from them. They defeated Australia 1-0 on Monday to make their maiden Olympic semi-final.

India's squad of 16 will be remembered for their team work

It was a momentous occasion for hockey, which is so intricately linked with India's sporting glory.

India once ruled field hockey, mainly when it was still played on a natural field. While the men were put on a pedestal, women were largely ignored.

India has won 11 Olympic medals, including eight golds, in hockey. But the women's team, which made its debut in 1980, has played in only three editions, including Tokyo.

Most of the women in Indian hockey came from impoverished backgrounds and were used to making do with meagre resources and official apathy. At times, the promise of a government job and a steady salary had to suffice over athletic dreams. It wasn't till 2012 that efforts were put in to improve the women's game.

Former Australian player Neil Hawgood recalled the diffidence in the team when he arrived as the coach in 2012. He had to convince them that he was there to help them succeed rather than blame them for the failures.

"We had to get them to trust us, and that was the biggest key," Hawgood told the BBC.

"Deep Grace Ekka and Sunita Lakra took about two years before they would look me in the eye…By 2014, that trust had been developed, and the team began to grow. Foreign coaches can say that (Indian players are meek), but to recognise and understand why that was there in the first place is and was where we made the biggest gains in the early years."

Under Hawgood, the Indian women's team qualified for the Olympics for the first time in 36 years.

Though the trip to Rio didn't quite go according to plan, they gained experience and some confidence. It proved to be an important first step, because it proved that they could work wonders when given the proper resources and tools.

With coach Sjoerd Marijne at the helm and Wayne Lombard revolutionising the way they train, Indian women's hockey has almost been brought up to speed.

In 1980, when the team travelled to Moscow Olympics, they were accompanied by a coach and a manager. At the Tokyo Games, they have a support staff of seven.

Gurjit Kaur's mother celebrates India's win at the quarter-finals

Over the last five years, the women's team has benefitted from a scientific, sophisticated approach towards the game.

Of the 16 players that are in Tokyo, eight of them had played at Rio 2016, giving the team a strong core. They have learnt from the experience, shared it and built upon it.

The pandemic threatened to throw a spanner in the works, but the Indian team stayed on the extra year in the Sports Authority of India campus in Bengaluru revising their lines, devising their plans.

India arrived in Tokyo prepared.

Their new-found confidence was evident in the way they refused to fade away against South Africa in the final group match or be intimidated by Australia in the semis.

Katariya, who once trained in isolation to hide from the reprimanding glances of elders in her village, thrived under the spotlight. She scored a hat-trick, first by an Indian woman at the Olympics, to help India edge South Africa 4-3 and stay alive in the competition.

Though there have been streaks of individual brilliance, like Katariya's, this squad of 16 will be remembered for their team work and commitment to each other.

They have all had their own journeys, their own stories of struggle, and have found strength in a common goal.

A lot of them had built their and their family's lives from ground up. Now, they are taking Indian hockey to greater heights.

Deepti Patwardhan is an independent sports journalist based in Mumbai.

Rani: 'We represent a billion people when we play'

- Published2 August 2021

- Published7 August 2021