Caste census: Clamour to count India social groups grows

- Published

Critics say the BJP fears that a caste count could spark more demands for quotas

Major opposition and regional leaders have met India's Prime Minister Narendra Modi to argue in favour of counting caste in the country's census.

"A caste census will be a historic, pro-poor measure," Tejashwi Yadav, a leader of the regional Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD), was quoted as saying by the Press Trust of India.

Mr Modi's Bharatiya Janata Party's decision not to do so has sparked a political maelstrom.

Hinduism's deeply hierarchical and oppressive caste system, which dates back some 2,000 years, puts Brahmins or priests at the top, and Dalits (formerly untouchables) and Adivasis (tribespeople) at the bottom.

In between are a multitude of castes - it's hard to even say how many because there is no list that has enumerated them all.

But there is a swathe of lower and intermediate castes, which are roughly believed to constitute about 52% of the population, that are recognised as Other Backward Classes or OBCs.

While India's census, which happens every 10 years, has always recorded the population of Dalits and Adivasis, it has never counted OBCs.

Now, several political parties, including BJP's allies, are demanding a caste census - essentially a count of OBCs. However, the government has refused.

Why is the BJP opposed to a caste census?

The ruling party has said it will not do a caste count "as a matter of policy", but critics say the move is calculated.

Elections are due next year in the battleground state of Uttar Pradesh, and experts believe the BJP is reluctant to stir any issues that may bring unwelcome surprises - especially after it was routed in recent state polls in West Bengal.

Caste is a crucial factor in every Indian election, from the village council to the parliament. More so in Uttar Pradesh, where the BJP's power and popularity rest on a delicately forged alliance of castes, and especially those in the OBC category.

A caste count could cause fissures in the Hindu vote, which the BJP has managed to consolidate in recent years, despite deep divisions that underpin the party's plank of Hindu unity.

The government has also argued that it would lead to the perpetuation of caste identities - but lower castes say that identity is a reality they grapple with everyday and only the privileged can afford to overlook caste.

Critics say there's another reason for the BJP's reluctance. Counting OBCs would reveal what a large proportion of the population they make up, but how little of it comprises upper castes, who nevertheless dominate politics and bureaucracy, because of centuries of privilege afforded by wealth and education.

Does India need a caste census?

Given that the census already records a gamut of data, from religion to language to socio-economic status, and also counts Dalits and Adivasis, many experts say there is no good reason not to count OBCs.

They are the targets of some of India's biggest affirmative action programmes - quotas in government jobs and colleges - and by most estimates account for a little over half the population.

Dalits, among India's most marginalised groups, are at the bottom of the Hindu caste system

Economists and policy makers have long argued that counting OBCs can better inform government programmes and efforts.

It's far from uncommon for governments to do this. The United States counts people by race and the UK enumerates country of origin for its immigrant population.

In fact, the British, who began India's census operations in 1872, counted all castes until 1931.

However, since 1951, independent India's census only counted the castes of Dalits and Adivasis, referred to as scheduled castes and tribes respectively. Everyone else's caste was marked as general.

Has India ever counted its OBC population?

Not really - there have been estimates but there is no official, published data.

The 1980s saw the rise of several regional caste-based parties that challenged the dominance of upper castes in India's two major national parties - Prime Minister Narendra Modi's BJP and the main opposition Congress.

This also mobilised lower castes to demand quotas in government jobs and colleges across India.

Since 1950, India has reserved government jobs, college admissions and elected seats - from village councils to the parliament - for Dalits and Adivasis to rectify historical wrongs that have denied them equal opportunities.

While the constitution allows the same for "other socially and educationally backward classes", it doesn't specify or define who they are.

In 1979 the federal government appointed a commission to identify these castes and determine whether existing affirmative action programmes must be extended to them.

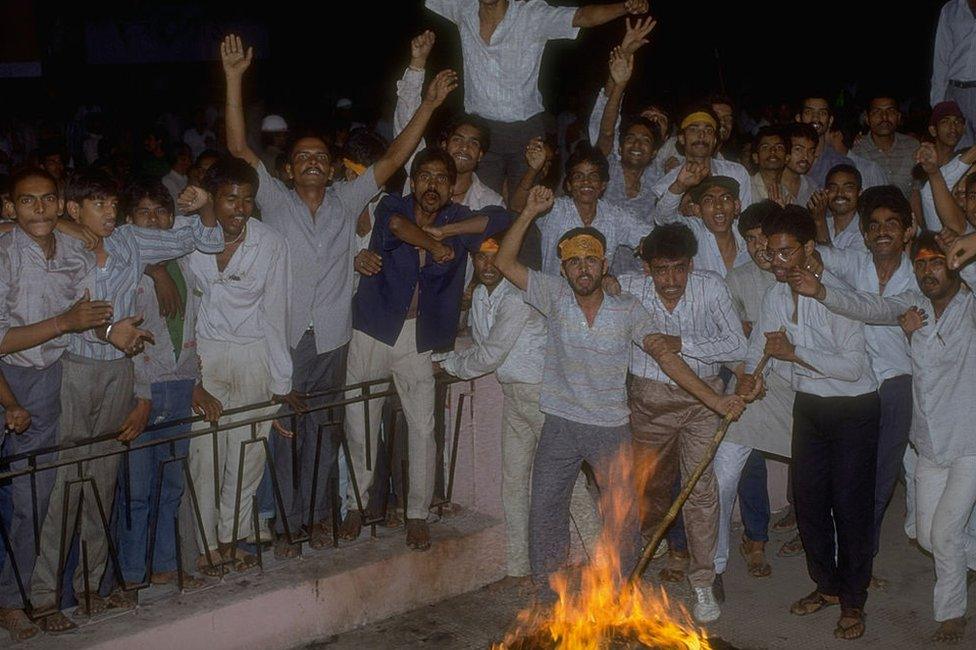

The Mandal commission report sparked huge protests by upper caste students

The Mandal commission, named after the MP who headed it, recommended extending the quotas to OBCs - but this wasn't implemented until 1990 by a National Front government led by VP Singh.

It was met with huge protests from upper caste groups, especially students - the Indian economy had not yet opened up then and limited government jobs and college seats were in high demand.

The BJP is not the first to rebuff an OBC count. Successive Congress-led governments have also shied away from it. The Congress was forced to concede in 2010 when an overwhelming majority of MPs supported a caste census.

The results of the Socio-Economic and Caste Census initiated in 2011 were never released.

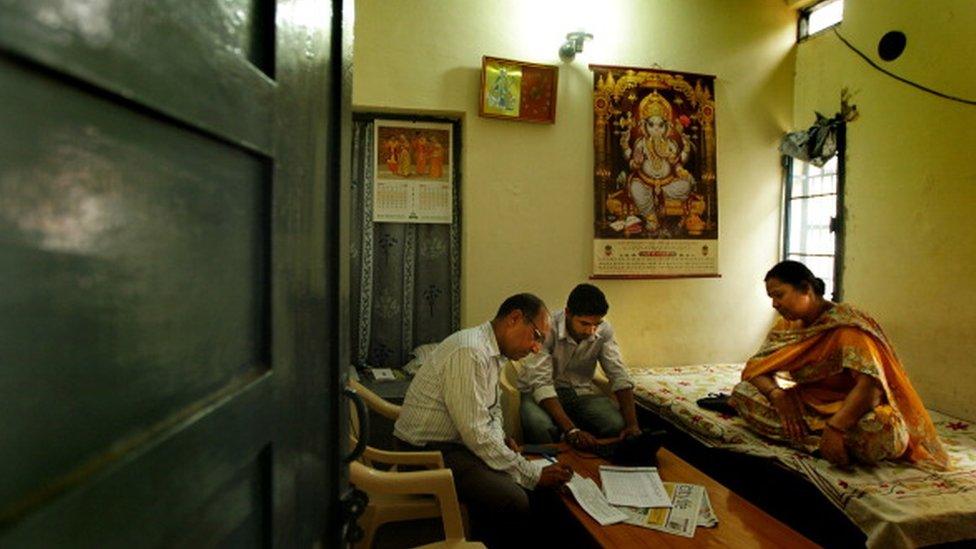

India's exhaustive census has never counted OBCs

Critics say a new count would reveal how the OBC population is well in excess of the 52% identified by the Mandal commission, spurring demands for more quotas. And the timing wouldn't be worse for the BJP.

Data suggests the party has done well among OBCs, especially in UP in the last two elections, but a renewed demand for quotas will put it in a tough spot.

The BJP is still an upper caste party - and more important, if it alienates the OBC vote, that could give the opposition a much-needed platform to counter the BJP.

Meet Marichamy - India's lower-caste Hindu priest