In India, growing clamour to criminalise rape within marriage

- Published

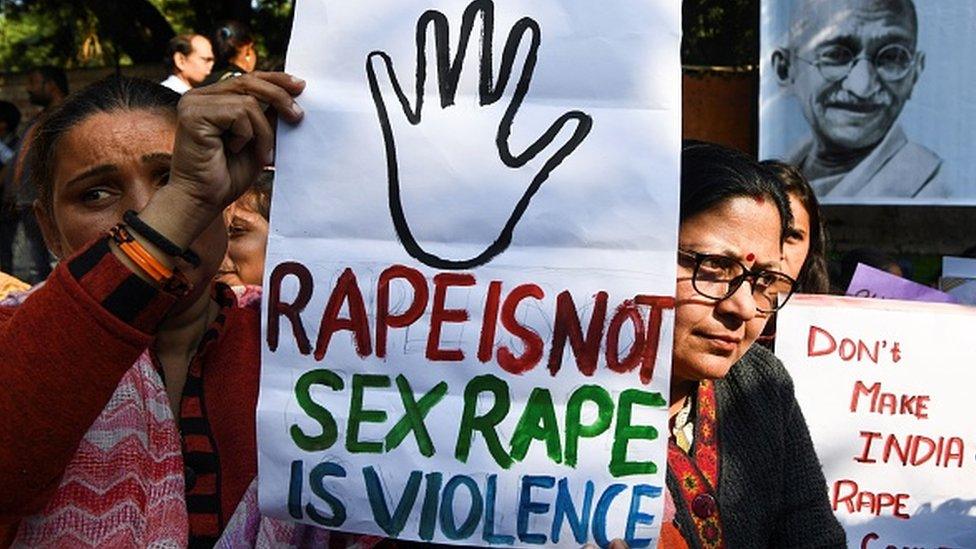

In India, a society rooted in patriarchal traditions, marriages are sacrosanct and it is not a crime for a man to rape his wife.

But in recent weeks, courts have given conflicting rulings on marital rape, leading to renewed calls from campaigners to criminalise rape within marriage.

On Thursday, Justice NK Chandravanshi of the Chhattisgarh high court ruled that "sexual intercourse or any sexual act by a husband with his wife cannot be rape even if it was by force or against her wish".

The woman had accused her husband of "unnatural sex" and raping her with objects.

The judge said the man could be tried for unnatural sex, but cleared him of the much more serious offence of rape since Indian law does not recognise marital rape.

The ruling met with outrage on social media, including from gender researcher Kota Neelima who asked "when will courts consider the woman's side of the story?"

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Many responded to her tweet saying the archaic rape laws must be amended - but there were many contrary voices too.

One wondered "what sort of a wife would complain of marital rape?"; another suggested "there must be something wrong with her character"; while a third said "only a wife who doesn't understand her duties would make such a claim".

It's not just social media, the contentious topic of marital rape also appears to have divided judiciary.

Just a few weeks back, the high court in the southern state of Kerala ruled that marital rape was "a good ground" to seek divorce.

"The husband's licentious disposition disregarding the autonomy of the wife is marital rape, albeit such conduct cannot be penalised, it falls in the frame of physical and mental cruelty," Justices A Muhamed Mustaque and Kauser Edappagath said in their 6 August order, external.

They explained that marital rape occurred when the husband believed that he owned his wife's body and added that "such a notion has no place in modern social jurisprudence".

In India, marriages are considered sacrosanct

The law that Justice Chandravanshi invoked is Section 375 of the Indian Penal Code.

The British colonial-era law, which has been in existence in India since 1860, mentions several "exemptions" - situations in which sex is not rape - and one of them is "by a man with his own wife" who's not a minor.

The idea is rooted in the belief that consent for sex is "implied" in marriage and that a wife cannot retract it later.

But it has increasingly been challenged across the world and over the years, more than 100 countries have outlawed marital rape. Britain too outlawed it in 1991, external, saying the "implied consent" could not be "seriously maintained" nowadays.

But despite a long and sustained campaign to criminalise it, India remains among 36 countries where the law remains in the statue book, leaving millions of women trapped in violent marriages.

According to a government survey, external, 31% of married women - almost one in three - have faced physical, sexual and emotional violence from their husbands.

"In my opinion," says Professor Upendra Baxi, emeritus professor of law at University of Warwick and Delhi, "this law must be struck down."

Over the years, he says, India has made some progress in addressing violence against women by bringing in laws against domestic violence and sexual harassment, but has done nothing about marital rape.

In the 1980s, Prof Baxi was part of a group of eminent lawyers who had made several recommendations on amending rape laws to a committee of MPs.

"They accepted all our suggestions except the one on outlawing marital rape," he told the BBC.

Their subsequent attempts to get the authorities to criminalise marital rape also remained unsuccessful.

"We were told the time was not right," Prof Baxi said. "But there has to be equality in marriage and one side cannot be allowed to dominate the other. You cannot demand sexual service from your spouse."

The government has consistently argued that criminalising marital law could "destabilise" the institution of marriage and that it could be used by women to harass men.

But in recent years, many unhappy wives and lawyers have petitioned courts calling for the "offending law" to be struck down.

United Nations, Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International have also raised concerns about India's refusal to do so.

Many judges too have admitted that they are hobbled by an archaic law that has no place in a modern society and called for the parliament to criminalise marital rape.

India is among 36 countries where marital rape is not illegal

The law is "a clear violation" of women's rights, and the immunity it provides to men is "unnatural" and the main reason behind the growing number of court cases, Ms Neelima says.

"India has a facade of being very modern, but scratch the surface and you see the real face. The woman remains the property of her husband. Rape is criminalised in India not because a woman's violated, but because she's the property of another man."

Ms Neelima says "one half of India that is male became free when India became an independent country in 1947, the other - female - half is yet to be free. Our hope lies in the judiciary".

It's encouraging that some courts have "admitted the unnaturalness of this immunity", she says. But these are "small wins, overrun by other contrary legal verdicts".

"This needs intervention, and it must change in our lifetime. The barriers are extra tall when it comes to marital rape," she says.

"This should have been sorted out way back. We are not fighting for the future generations, we are still fighting the wrongs of history. And this fight is critical."

Read more from Geeta Pandey on patriarchy within homes: