The 9/11 attacks: 'Pain is like a sharp knife, which dulls over time'

- Published

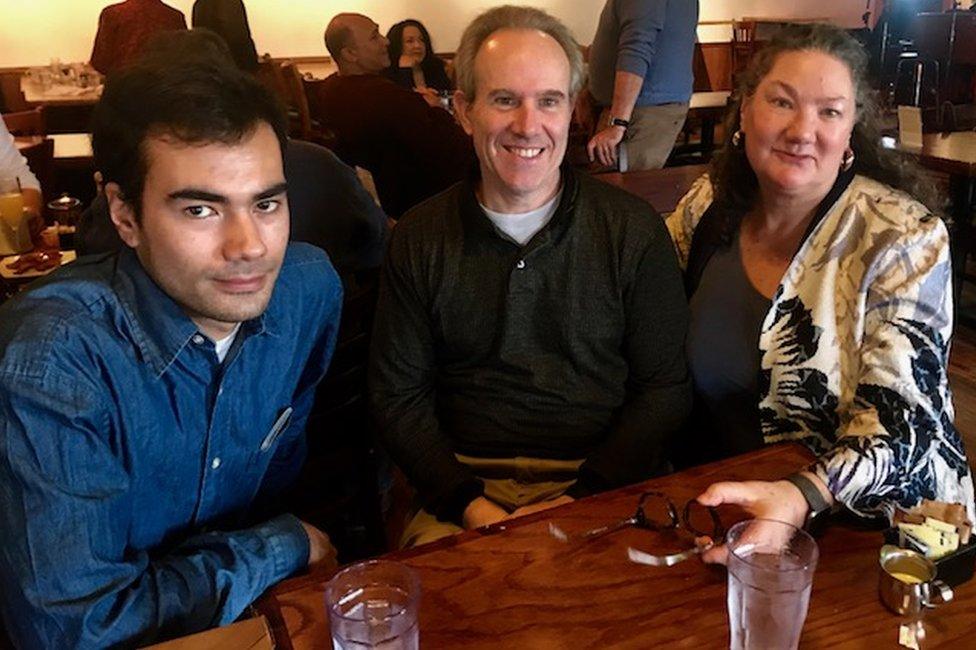

Jupiter with his son, Santi, in Beacon, New York

Jupiter Yambem had opted to work the morning shift at a restaurant in the World Trade Center on 11 September, 2001, to spend more time with his five-year-old son, Santi.

The night shift at Windows on the World, the restaurant atop the North Tower of the tallest buildings in New York City, had left him with little time for his family. All he wanted to do was play football with Santi, teach him to ride a bike, do the usual things a dad does.

On that Tuesday, Jupiter woke, showered, got dressed, kissed his wife, Nancy, and drove off into the night. Soon dawn broke into a crisp and clear early autumn day.

Jupiter, who arrived in the US from the north-eastern Indian state of Manipur in 1981 to attend a summer camp for visually impaired children at Vermont, had worked his way up to a banquet manager's position at the prestigious restaurant.

For five years, the 110-storey twin buildings had been his workplace. Some 50,000 people worked across the 16-acre complex, and tens of thousands visited the place daily for business, shopping and meals at Windows on the World.

On 11 September, Jupiter was responsible for a technology conference that the restaurant was hosting.

Windows on the World offered diners stunning views of New York City

At home in Beacon, Nancy prepared for a busy day.

Santi was in his second week of kindergarten, and she followed his bus to school because it was running late every day and she wanted to know what time it got there to report to his principal. Then she drove off to work, a residential home for people with mental health and drug problems, in Orangeburg, some 40 miles (64km) away.

When she reached work, someone told her a jet plane had struck the World Trade Center.

"Everyone was watching TV. I didn't see the planes hit the buildings," Nancy told me from her home in New York state.

At 8:46 local time (12:46 GMT) American Airlines Flight 11 had hit the North Tower between the 93rd and 99th floor, trapping everyone in the floors above.

People choked as the thick, black smoke enveloped Windows on the World. The assistant general manager of the restaurant made frantic calls to officials seeking advice to "direct our guests and our employees, as soon as possible".

A participant at the conference called a colleague saying there had "been a huge explosion, all the windows had fallen out, all the ceilings had come down, and everyone had been knocked to the ground, but everyone was okay, and everyone was going to be evacuated".

But none of them made it outside.

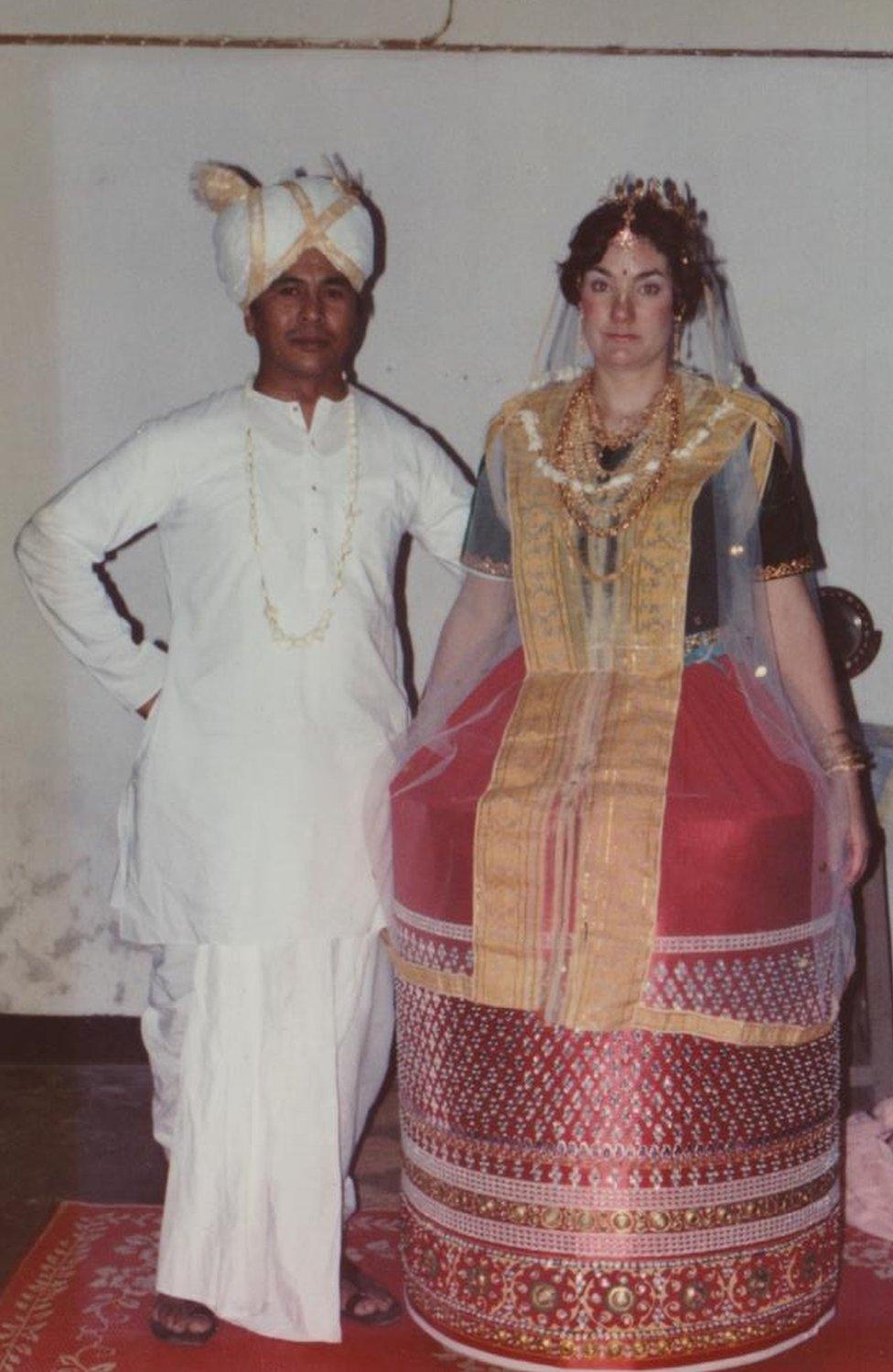

Jupiter and Nancy on their wedding day in Manipur in 1991

The chef, who was supposed to be at work by 8:30, stopped to get new spectacles in a shop under the tower and survived. It took days to count the dead at the restaurant - 72 people died at Windows on the World that morning.

"I saw the towers implode and collapse in complete shock and disbelief. I called his phone again and again. He didn't pick up," Nancy said.

Rescuers quickly recovered Jupiter's body on the top of the rubble. The family provided a DNA sample from his hairbrush, and by the weekend he had been identified.

"We were very blessed. We had a proper funeral, and we collected his ashes. Many were not so lucky," Nancy said. Two decades after the incident, the remains, external of only around 1,600 of the 2,754 victims have been identified.

Jupiter was 42 when he died, and Nancy, who was then 40, had known him for two decades.

He was studying economics and she music therapy when they met in college in 1981. Jupiter would come to a deli where she worked to meet her, and they bonded over a slice of carrot cake which they would share. When they got married in 1991, they ordered a carrot cake. Folk singer Pete Seeger, a family friend of Nancy's, sang at the wedding.

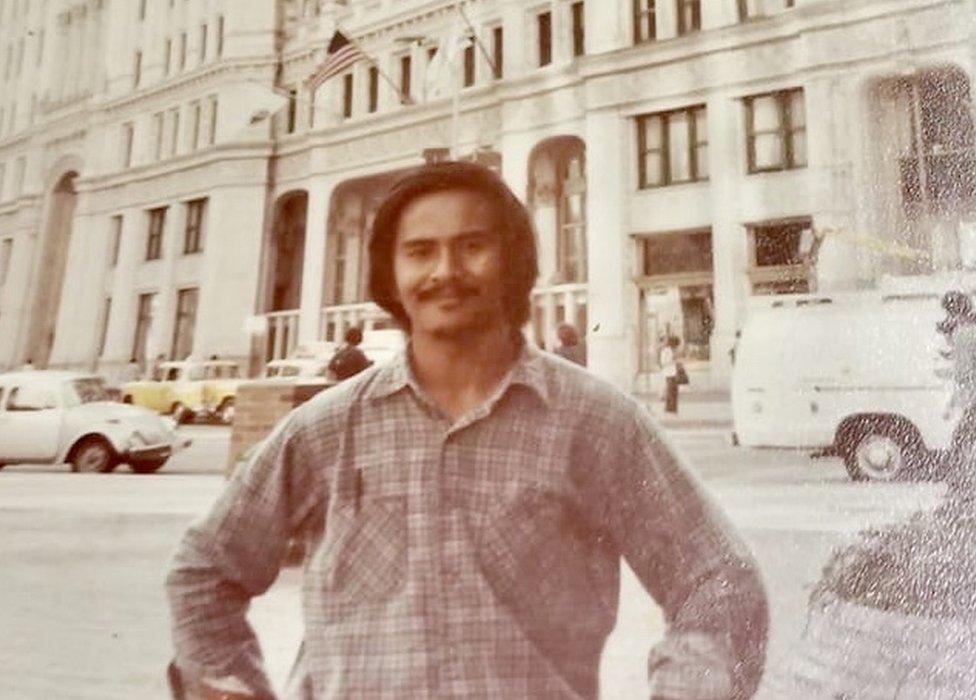

Jupiter came to the US in 1981

Growing up in north-eastern India, Jupiter, born to a doctor mother and an engineer father, was the youngest of five brothers. After finishing school, he learnt German in Delhi. He was an amiable and friendly man, "my best friend, really," remembers his elder brother, Yambem Laba.

Nancy found him a "a real dude... a ladies man". Jupiter was a "good sportsman, and held a record in long jump in his school in India. He loved music."

"You know, he was very gregarious. He lit up a room."

Jupiter was proud of his job at Windows on the World. He would return home, breathlessly exulting about the celebrity diners he had met: Bill Clinton; broadcaster Barbara Walters; figure skater Kristi Yamaguchi. "His biggest regret was he did not have his picture taken with Mr Clinton, his favourite president," Nancy said.

On a beautiful Tuesday morning it all came to an end. A painful void followed.

"The first year I could not sleep. I cried myself to sleep every night," Nancy said.

"How did this happen, I wondered. How could people hate us so much? I began reading, I began learning. In my heart, I forgave the terrorists.

"I told myself there was no way I could live with hate. I had to get a new life. I needed to find out who I was again."

About a year and half later, Nancy began dating. In 2006, she married Jerry Feldmann, a civil engineer. "Love saves you in the end," she said.

Santi Yambem, Jerry Feldmann and Nancy Yambem in New York

Not a single day passes when she doesn't think of Jupiter, Nancy said. There's a small shrine at home to remember him. She donated things that Jupiter had received from Windows on the World to the 9/11 museum: his business card, two bottles of wine from a special event, and a wooden wine kit box.

The family travels to Jupiter's home in Manipur every few years. Santi, who's 25 and works in a restaurant in Beacon, has learned to play the pung, a traditional Manipuri drum. "Our second home in Manipur is Jupiter's link with his dad," said Nancy. "It's important be in touch with your roots."

If Jupiter were alive, the couple would have been celebrating their 30th wedding anniversary in October.

"Trauma is a strange thing," Nancy said. Forgetting "isn't an option", but reliving 9/11 every year can be hard.

"Pain is like a knife which is very sharp and intense in the beginning. With time, the knife gets blunter and the pain gets duller."

‘I saw the world as a scary place for the first time’