Climate change: What emission cuts has India promised?

- Published

Many Indians have been participating in global climate strikes

India has submitted updated climate change pledges to the UN, based on commitments made by Prime Minister Narendra Modi to tackle global warming at the COP26 meeting last year.

Climate scientists say temperature rises must slow down to avoid the worst consequences of climate change.

What are the pledges India has made?

In its pledges - known as Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC) - India has said it will reduce the emissions intensity of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) by 45% by 2030.

This is a measure of the amount of greenhouse gas emitted per unit of economic activity, and India now has a more ambitious target than the 33-35% cut which was set before COP26.

But a fall in emissions intensity does not necessarily mean a reduction in overall emissions.

Your device may not support this visualisation

India was the third largest emitter of carbon dioxide by volume in 2020, although its per capita emissions were lower than the world average, according to the UN's Emissions Gap Report (EGR).

Its target date to reach net zero emissions remains 2070 - much later than the date set by many other countries and not in line with the Paris agreement, which proposed 2050 as the target date for net zero to keep global temperature rises to 1.5C.

Net zero is where a country is not adding to the overall amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

India has also confirmed pledges to generate 50% of its electricity from non-fossil fuel sources by 2030, and its target for maintaining forest cover, which acts as a carbon sink.

However, Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced at the last COP a target for 500 GW of its energy capacity to be from non-fossil fuel sources by 2030.

But that does not appear in the updated pledges given to the UN.

What targets could India achieve by 2030?

Climate Action Tracker, which monitors the actions of governments globally, says India's new goals are "stronger on paper" than previous pledges.

But it adds that the new targets will not be enough to achieve the goal of limiting global temperature increases to 1.5C, because India's emissions will not peak by 2030.

Nandini Das, a climate and energy economist at Climate Analytics, says India could help limit global temperature rises to 1.5C - but only if its emissions peak as soon as possible and if by 2030 they have dropped by 16% from their 2005 levels.

"If you achieve the peak earlier, it's easy to plan your energy transition for the second half of the century," Ms Das says.

Rameshwar Prasad Gupta, India's environment secretary, said last year that the country's emissions would peak between 2040 and 2045 and then decrease.

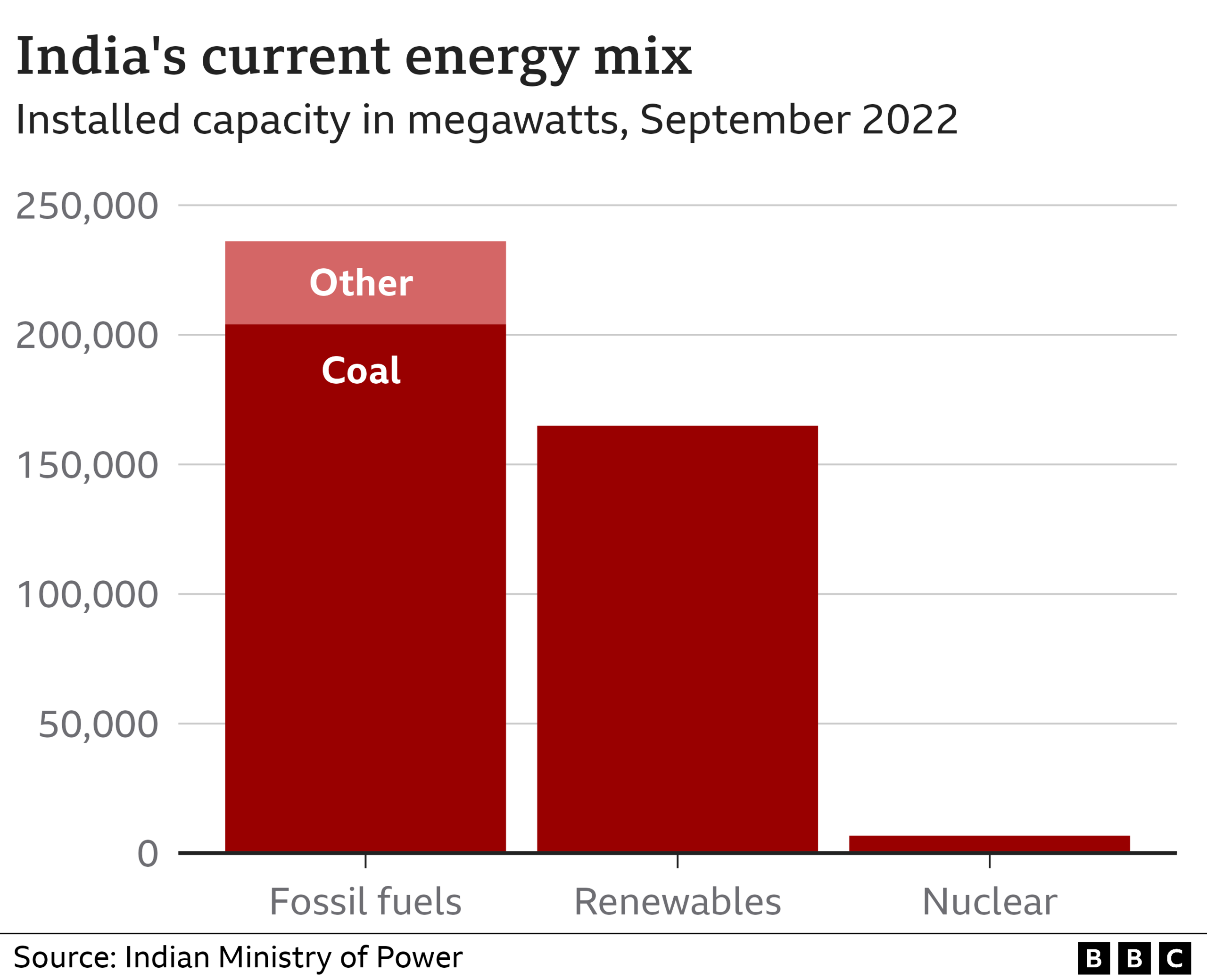

India is heavily reliant on coal for power generation

India currently has the capacity to generate just over 40% of its power from renewable sources as of September this year, so the 50% target is achievable by 2030, according to the UN and Climate Action Tracker.

But International Energy Agency (IEA) data shows coal continues to be a major source of power generation.

And India's coal requirement is set to increase by 50% in the next decade, going by official estimates.

Ms Das says India is sending out mixed signals as it is "rapidly expanding its renewable capacity, but at the same time increasing coal consumption".

India has also abstained from signing a deal agreed at COP26 last year to reduce emissions of methane gas, one of the most potent greenhouse gases, of which India is a major emitter.

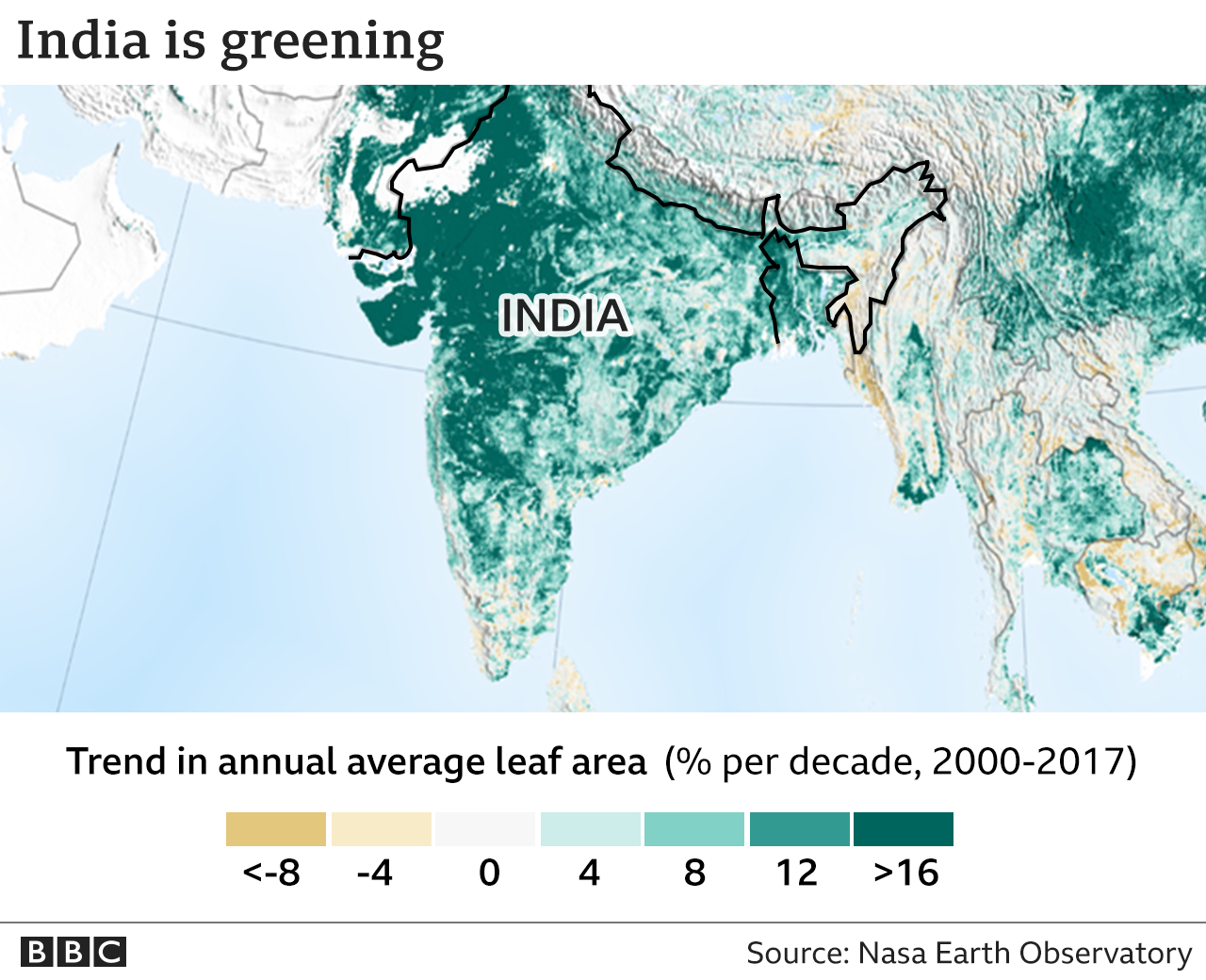

Are India's forests expanding?

India has highlighted many times that it wants to bring a third of its land area under forest cover, which can help absorb carbon from the atmosphere.

India plans to plant enough trees by 2030 to absorb an additional 2.5-3 billion tonnes of CO2 from the atmosphere.

Although there have been replanting initiatives in the southern parts of India, the north-eastern region has lost forest cover.

Global Forest Watch (GFW) - a collaboration between the University of Maryland, Google, the United States Geological Survey and National Aeronautics and Space Administration (Nasa) - estimates India lost 19% of its primary forests and 5.3% of its tree cover between 2001 and 2021.

But the Indian government's own data indicates a 5.2% increase in total tree and forest cover in the same period.

The difference is explained by the fact that GFW counts only vegetation taller than 5m (16ft), whereas India's official figures are based on the density of all types of trees in a given area of land.

According to government data, India's forest cover stands at 24.6% of the country's total area as of 2021. However, that estimate has been questioned by some experts., external