'Why do you like Shah Rukh Khan?'

- Published

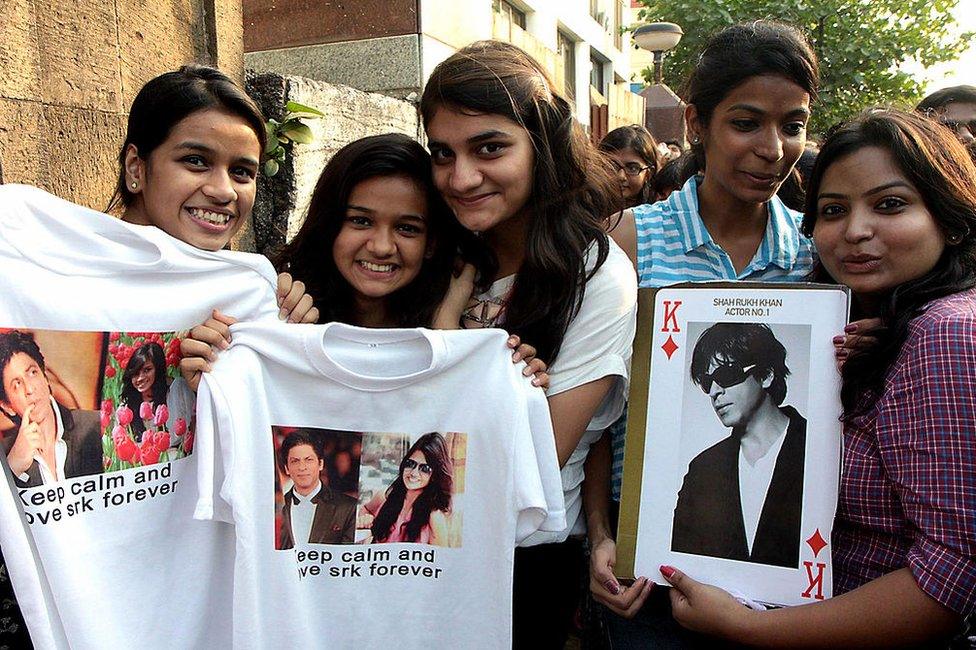

Khan is one of Bollywood's biggest superstars

"Why do you like Shah Rukh Khan?"

I put the question about the Bollywood superstar to a couple of my friends recently. They were taken aback - it wasn't a question they had ever considered. I hadn't either, but a new book, Desperately Seeking Shah Rukh, made me wonder.

They said he was "charming" and "relatable" as a hero, "funny", "sarcastic" and "candid" in interviews, and "unapologetic" about his pursuit of fame and money. When I pressed, they thought more deeply about the roles he played, remarking on how he was never a "macho" hero, but sensitive and head-over-heels for the women he professed to love.

"It's true! We love him for his love of women!" one of my friends declared, surprising herself with this realisation.

That is exactly what author Shrayana Bhattacharya found when she asked the same question of dozens of women, all fans of Khan.

But startlingly, these stories of his female fandom are, in effect, a tale of economic inequity.

"In telling me about when, how and why they turned to Shah Rukh, they are telling us about when, how and why the world breaks their heart," writes Ms Bhattacharya, unspooling the dreams, anxieties and mutinies that are inexorably linked to the romantic choices women make in a world that forever puts them at a disadvantage.

This is no hurried survey. It spans nearly two decades of encounters, conversations and friendships with single, married or somewhere-in-between women in northern India. They are Hindu, Muslim and Christian, happy and unhappy homemakers, content and frustrated working women, and resigned and restless working class women. They are united only by their fandom.

Khan swept into our lives in the 1990s, along with Coca-Cola and cable TV, proof of a new era, when a slew of economic reforms threw open India to the world - what we call liberalisation.

"I wanted to tell a story of those 'post-liberalisation' women and I found in Khan an unusual ally," Ms Bhattacharya says. And how.

Khan has legions of female fans

She was surveying incense stick makers in an urban slum in western India in 2006 when she found that they grew bored with the usual questions about wages. So, during a break, she started chatting to them, asking them about their favourite Bollywood hero.

"They were much more interested in talking about what delights them and what delighted them was Shah Rukh."

It became an ice-breaker in subsequent surveys and soon Ms Bhattacharya found that these women were united not just by Khan but also "an unequal labour market and their own struggles at home". And that didn't change even when she spoke to middle class or wealthy women.

Why can't more boys and men be like the Shah Rukh on screen? was a common litany. "They are constructing him - they are all making him up and they are making him up based on their reality and their aspirations," Ms Bhattacharya says.

Khan's utter devotion to the heroine signalled a man who would pay real attention, actually listen to a woman. His anxiety about his fate, a defining feature of many of his roles, made him an ideal partner for women, whose lives are rarely in their own hands. His visible vulnerability - Khan was always a messy crier, a rarity for a Bollywood man - meant he didn't shy away from showing his feelings or caring about theirs.

"I wish someone could talk to me or touch me the way he does with Kajol in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, external, but that's never going to happen. My husband's moods and hands are so harsh," says a young Muslim garment worker.

The rich, unhappily married daughter of erstwhile royals said she wanted to bring up her sons to be "good men". Her definition: they "can cry and they make their wives feel like Shah Rukh makes us feel, safe and loved".

These are not merely gushing fangirls, blind to Khan's more problematic roles, which included stalking and violence.

Rather, theirs is a critical gaze. They didn't approve of those films and they say so.

What stayed with them wasn't the glamour or the drama - although they thoroughly enjoyed that - but the seemingly inconspicuous moments.

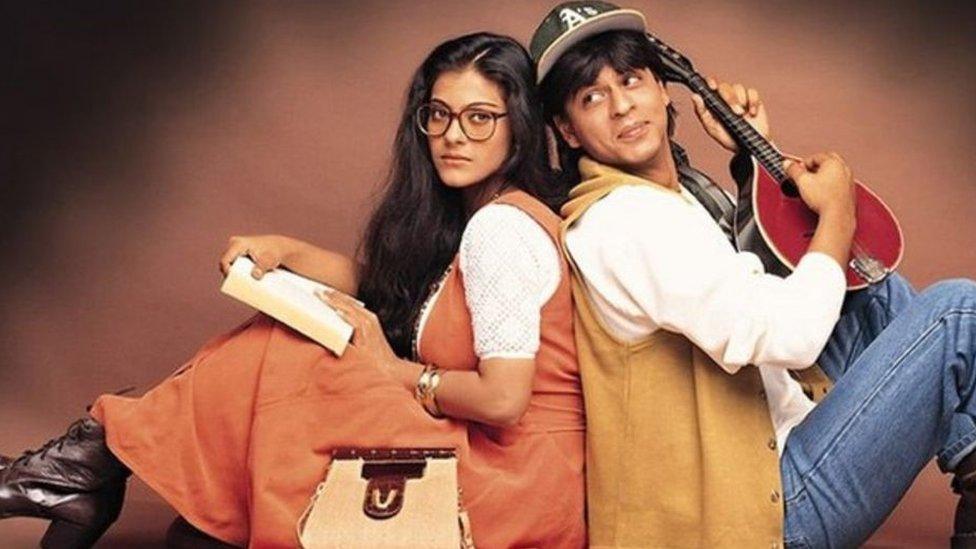

Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jayenge was one of Khan's biggest hits and possibly Bollywood's most successful and beloved romance - but the mother of a fan girl was struck by something I don't think I ever noticed: "It was the first time I had seen the hero peel a carrot in a film and spend so much time with the women of the household."

To her, that was incredibly romantic. It's not that these women didn't speak of lust or sexual attraction, which was expected, but they spoke of so much more.

Khan and Kajol (L) starred in several films together

Khan was a distraction from the humdrum or a reprieve from heartbreak and daily injustices. He was the man they wanted to marry not because he was a Bollywood star, but because he was considerate. And a considerate man would let you work, save money, or at least allow your dreams to live - even if all that meant was taking you to the cinema hall to watch the next Shah Rukh-starrer.

For so many of his female fans - the bureaucrat whose mother slapped her when, as a teenager, she snuck off to the cinema to watch a Khan film; the young garment worker who had to bribe her brothers with hard-earned money to be able to catch Khan's latest film on the big screen; the domestic help who lied to her priest so she could skip church four Sundays in a row to watch Khan's films on TV - the simple joy of watching a film is a stolen freedom.

In fact, many of his poorer fans never watched a movie of his until much later in life, relying instead on songs to feed their fandom. But even that can be frowned upon.

"It's extremely difficult for women to just have fun - listen to a song or star-gaze at an actor," Ms Bhattacharya says. "When a woman says she likes an actor, she is saying she likes the way a man looks and will probably be judged for it."

These women may not be radicals, Ms Bhattacharya writes, but in seeking these indulgences, these simple joys, they rebelled. They rebelled by hiding his posters under their bed, listening and dancing to his songs, and by watching his films - and because of those rebellions, they realised what they truly wanted from life.

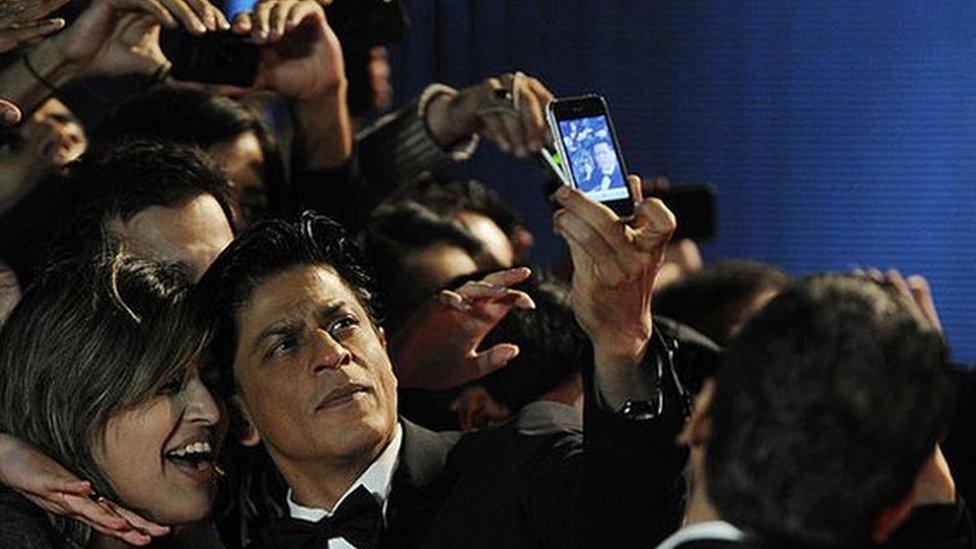

Khan has starred in more than 100 films in a career spanning three decades

The bureaucrat, for instance, was determined to make her own way in the world because she never again wanted to ask permission to watch a Khan film. One young woman ran away from home when a secret trip to the cinema for a Khan film led to a hurriedly arranged match with a man who was not a fan and disapproved of the fact that she was. (She has since become a flight attendant and married a man who "evoked the same feelings" as Khan).

Khan was not such a delicious promise or forbidden dream for my friends and I, whose privileged world afforded far greater freedom. Until I read this book, I never fully appreciated the quiet rebellion in my mother and aunt's sheer enjoyment of trip to the cinema nearly every Friday for the late-night show. I was taken along, oblivious to my good fortune.

But he is nevertheless a common thread that connects our disparate childhoods - one of the women said Khan taught her better English through his interviews. Well, he taught me Hindi.

Ms Bhattacharya says he is also an icon of his time - and a lot has changed since he stormed into Bollywood.

"The younger women don't want to marry Khan, they want to be him - they want his autonomy and his success."

Shrayana Bhattacharya's Desperately Seeking Shah Rukh: India's Lonely Young Women and the Search for Intimacy and Independence is published by Harper Collins India